Cosmic Europe

Merkur 12/2025

Leibniz’s Europe; why majority rule is relative; social chromatics off the scale; travels in post-capitalism.

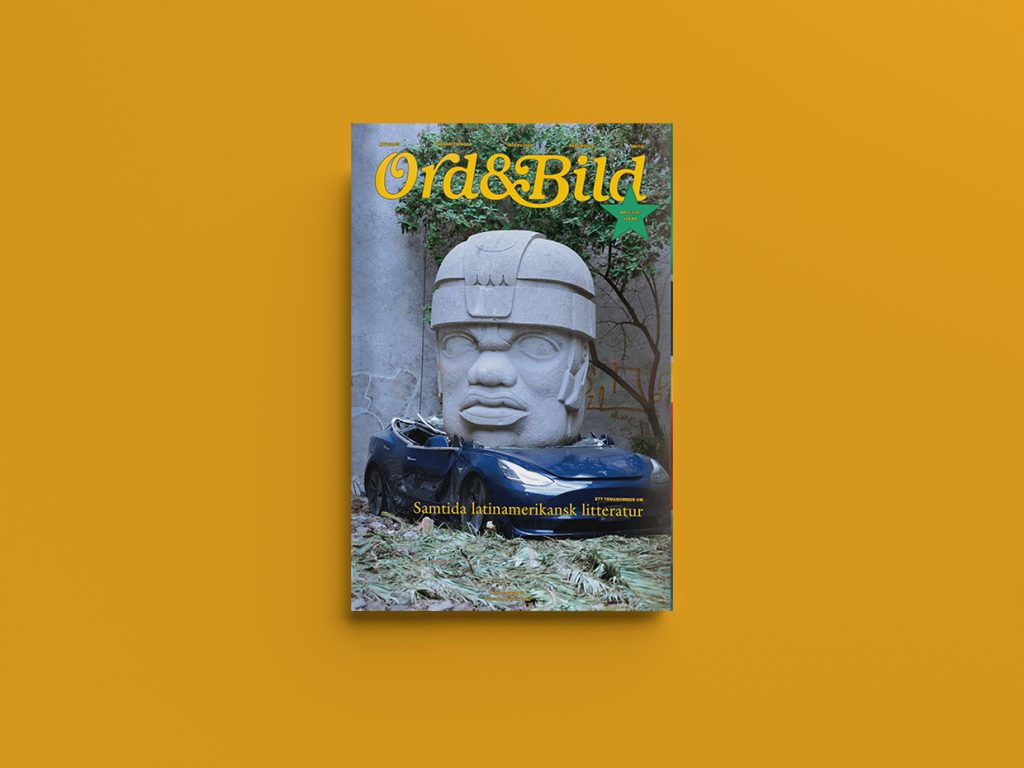

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.

In its current issue on contemporary Latin American literature, Ord&Bild lives up to its name (‘Word&Image’). The cover and accompanying photo essay by the Mexican artist Chavis Mármol show a colossal Olmec head that looks like it is made of stone. Yet a bicyclist can ride with one strapped to his back as though he were delivering a hot meal. The inspiration for these replicas date from at least 900 BC. The replica photographed on the cover sits on top of a crushed Tesla.

Mármol’s photos seem to ask, what is contemporary about the contemporary? Is it simply a facade hiding historical violence? Or is the contemporary a reckoning with that violence? The Tesla and the Olmec head are both in a way expendable – one is easily crushed, the other is a kind of fake. Yet Latin American history emerges in this issue with a colossal weight, threatening to crush people’s dreams for another future.

Another photo essay in this issue, by Teresa Margolles, is entitled ‘Pistas de Baile’ (dancefloors). As editor Johan Habib Engqvist explains, the photos are of trans sex workers in Ciudad Juárez, each standing amidst the ruins of former dance clubs. The subjects are both proud and vulnerable. Their work amidst the city’s exclusionary regeneration projects speaks to their precarious existence – indeed, one of the sex workers has been killed since their photo was taken.

Nona Fernández’s essay ‘How can thirst be remembered?’, which was published as an artist’s book in Santiago on the 50th anniversary of the military coup, is also about ruins. It begins with an iconic photo of the Chilean army’s bombing of La Moneda, the presidential palace, on 11 September 1973. Fernández explains how the military, led by Augusto Pinochet, demanded the destruction of videos of the Popular Unity alliance, including footage of cultural personalities such as Pablo Neruda and Víctor Jara. But a young woman working in the archives of the state television agency simply destroyed the catalogue entries for these videos, leaving the videos themselves intact in the archive.

‘How is history written?’ asks Fernández, and ‘is there a before history?’ By way of example, Fernández relates how some of the rubble from La Moneda ended up filling a hole in the outskirts of the capital where a woman wanted to build her house. The woman’s sister and neighbour had previously moved out of the centre precisely to get away from the destruction of Allende’s presidency by the military junta. Yet now, the rubble that she was trying to escape was rising before her as building material. In Fernández’s parable, one can’t simply remember or forget; rather, memories are written the same way that history is made, with both therefore failing to become coherent.

Fernández is part of a generation who grew up under Latin American dictatorships and whose writing has been dubbed ‘litteratura de los hijos’ (‘literature of the children’). Co-editor Joel Kellgren travels to Chile to interview Fernández and other cultural workers and activists reckoning with the failed hopes of democratic reform since Pinochet’s junta left power in 1990. He attends to the contested memory work around the dictatorship’s human rights abuses, which includes 1,469 people who were disappeared. And at the Museum of Memory & Human Rights in Santiago Kellgren is moved by its memorial of the lives lost to the dictatorship.

At the same time, he reflects on the absurd fact that the museum’s archives of testimonials of human rights abuses during the junta have been barred from being made publicly available until 2055. ‘Here we have a museum built for the express purpose of remembering the crimes of the dictatorship, which is at the same time forbidden from sharing information, held at the museum, about the scale of those crimes.’

This issue includes Hanna Nordenhök’s translations of short stories by contemporary Mexican writers Fernanda Melchor, Luis Jorge Boone, and Emiliano Monge. Nordenhök travels to Mexico City to speak to these writers, who are themselves fixated on children in literature. Even here the perversions of memory are apparent. Melchor comments on the relationship between nostalgia and paedophilia, ‘the desire for a child can be a desire for the past. A past which perhaps hasn’t even existed’. She goes on to draw a connection between the desire for an innocent past, and populist leaders who promise to solve all problems if people submit to their power.

Argentinian writer Mariana Enríquez’s short story, ‘My sad dead’ (translated into Swedish by Hanna Axén), is told from the perspective of a doctor in Buenos Aires who has a special affinity for ghosts. When her recently deceased mother shows up in her house, she starts spending time with other dead people in her neighbourhood. The woman does her best to calm these ghosts, most of whom are teenage victims of gang violence, or themselves desperate thieves.

Argentina’s own killed and disappeared from the 70s and 80s echo in these many dead. Yet these ghosts also speak to the social fraying of the neoliberal present, where no one seems to have a home. Spending time with the dead seems to be a defining characteristic of contemporary Latin American literature.

Review by Joel Duncan

Published 4 November 2025

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Leibniz’s Europe; why majority rule is relative; social chromatics off the scale; travels in post-capitalism.

Throughout history, Belarusians have turned to their rich folklore traditions in harsh times. What may appear as a period of cultural stagnation is often a moment of resilience and creative revival. And the current wave of Belarusian folk texts, music and dance is no exception.