Two opposing interpretations of 1945 form the ideological core of today’s confrontation between Russia and the states of central and eastern Europe. Both are reactions to the collapse of the Cold War order.

Sinn Féin’s breakthrough in Ireland’s general election in February ended the century-long dominance of the ‘Civil War parties’ in the Republic. On the left, the victory was celebrated as providing a ‘mandate for change’. But Sinn Féin’s image problem remains an obstacle. Unjustly so?

On 8 February, only weeks before the coronavirus crisis broke, Ireland’s general election had delivered little short of a political earthquake. The result was remarkable in two respects. First, in what for almost a century had effectively been a two-party system dominated by the so-called ‘Civil War parties’ (from their origins in the post-independence war of 1922), Sinn Féin now emerged as a major parliamentary force, with the vote split almost exactly three ways. Second, given the strong antipathy between these three parties, a prolonged period of political paralysis seemed to be on its way.

The coronavirus crisis began to be felt in Ireland from mid-March, with infections and deaths both peaking in mid to late April, before slowly declining. The crisis has meant that the process of forming a new government has not been treated with the same urgency as it otherwise would have been: public opinion seems happy for the time being to have experienced ministers from the outgoing Fine Gael-led administration in charge of emergency responses. At the time of writing, there is still no new government. Long-lasting political stalemates have of course occurred in recent years in other countries in Europe, but they are something new for Ireland.

Much of the talk in the immediate aftermath of the vote was of a ‘mandate for change’, and in particular of a political shift to the left. The winner of the largest number of seats (38) was Fianna Fáil. Then, with 37 seats, came Sinn Féin, a party that is active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and which was, at least until the Belfast Agreement of 1998, commonly understood to be the political wing of the IRA. Next, with 35 seats, came Fine Gael. After the leaders followed the Greens, with 12 seats, and then three leftwing groups, Labour (on six seats), the Social Democrats (a little to the left of Labour, also on six) and Solidarity-People Before Profit, a loose alliance of groups of Trotskyist origin, on five. The Irish voting system also facilitates the election of significant numbers of independent candidates, twenty of whom were elected in February.

The political shift could scarcely be more clear. In the election Sinn Féin gained fifteen seats, while Fianna Fáil lost seven, Fine Gael twelve and Labour one. If elections were decided simply on momentum, then Sinn Féin would surely have a strong case for leading the next government: indeed in the immediate aftermath of the vote there were strong calls for the party’s ‘mandate’ to be ‘respected’. But the fact is that government formation is determined by arithmetic and, as it emerged quite clearly in the weeks after the vote, the number of elected deputies who did not want Sinn Féin in government was far greater than the number who did. The parties which lost most seats, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, look like they will form the core of the new government.

In addition to the dramatic surge of Sinn Féin, the Greens and the Social Democrats also made significant advances, the latter achieving equal standing with Labour. Early on, there had been much talk of a possible left-leaning, Sinn-Féin-led government. But if, for the sake of argument, one supposed that all leftwing parties, plus the Greens and a few independents, had been prepared to support this, the number of deputies would still have been considerably fewer than that required for a parliamentary majority. And that is to make some assumptions about the willingness of these parties to coalesce with Sinn Féin, assumptions that in many cases are unwarranted.

In order to grasp what is involved in the new political dispensation represented by February’s election result and the implications of a resurgent Sinn Féin for the political future of both parts of Ireland, one needs to be aware that political cleavages in Ireland have historically often taken forms other than left and right, and that an affiliation like ‘republicanism’, essentially a particular form of nationalism, has had greater salience than socialism, while sometimes also being able to graft itself onto that root.

Sinn Féin (Ourselves), a political organisation founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905 on a platform of cultural and economic nationalism, initially proposed for Ireland and Britain a dual monarchy system on the Austro-Hungarian model (a common monarch but separate governments). Its early progress was not spectacular in a political landscape still dominated by the constitutional nationalists of the Irish Parliamentary Party, but it was soon being infiltrated by members of the conspiratorial separatist organisation the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

In 1916, in the middle of the First World War, an insurrection was staged, chiefly in Dublin, organised by the IRB but also involving many Sinn Féin members: indeed it soon became known as ‘the Sinn Féin rising’. The uprising was quickly suppressed by the British and the seven signatories of the ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’, along with other perceived leaders of the uprising, executed.

The executions, together with other killings of civilians and, in 1918, the threat of general conscription into the British army, led to a massive shift in Irish nationalist sentiment. From a position of relatively little sympathy for the Rising in 1916, support for the gradualist Irish Parliamentary Party (the ‘Home Rulers’) was transported wholesale to separatist republicans whose aim was, like that of the father of Irish republicanism, the 1798 revolutionary Wolfe Tone, to completely ‘break the connection with England’.

In the general election of December 1918, the radical separatists, now presenting themselves as Sinn Féin, won 73 of the 105 seats in Ireland while the IPP, which had supported Irish enlistment in the European war, was virtually wiped out. Elected Sinn Féin members declined to occupy their seats in the British House of Commons, instead establishing a parliament in Dublin, the Dáil Éireann (Assembly of Ireland), and beginning to set up the institutions of an independent state.

In September 1919 the British declared the Dáil illegal. It became evident that the clearly expressed preference of the majority of Irish voters for separation and independence would be no more respected than the previous demand for Home Rule within the United Kingdom, backed by a large majority of Irish voters since the 1880s. From 1919 to 1921, militant Irish republicans, now organised in the Irish Republican Army, took up arms in pursuit of independence. At least 1,400 people died in this guerrilla war, which came to an end in 1921 with a truce, followed by the signing of a peace treaty (the Anglo-Irish Treaty).

The Irish did not secure the full independence they sought but rather a largely self-governing ‘Free State’ encompassing 26 of the 32 Irish counties. The six north-eastern counties, with their large Protestant population, the descendants of seventeenth-century Scottish and English ‘planters’ installed to pacify rebellious Ulster, remained within the United Kingdom (a settlement thereafter known to nationalists as ‘partition’). Most of the leaders of the independence movement were prepared to accept this compromise, which they characterised as being not quite freedom but affording ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’ in the future. A minority, however, refused to accept anything less than a 32-county republic and a civil war was fought between the two sides in 1922 and 1923 in which thousands more died before the anti-treaty forces admitted defeat and dumped arms.

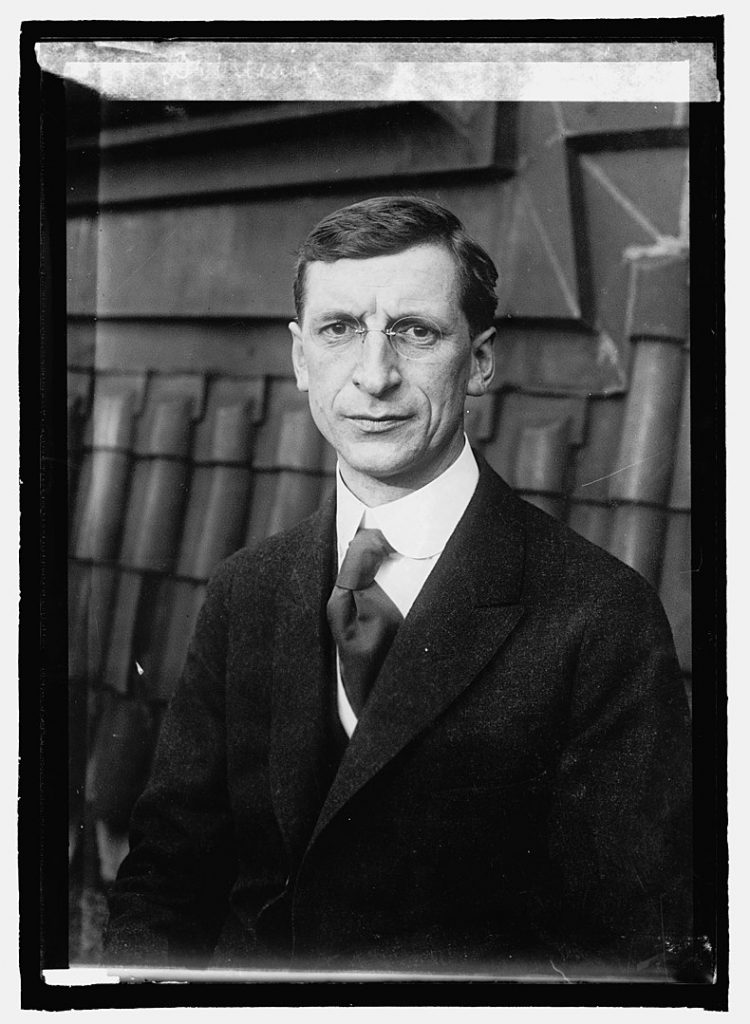

Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (to give it its full title) was founded in 1926 when most of the members of anti-treaty Sinn Féin (the pro-treaty elements having formed Cumann na nGaedhal, later to become Fine Gael) followed Éamon de Valera in abandoning their previous policy of abstentionism, taking up their Dáil seats to work for the eventual creation of a 32-county republic through parliamentary means. Although one prominent young deputy, Seán Lemass, three decades later to become an admired prime minister, referred in the late 1920s to Fianna Fáil as ‘a slightly constitutional party’, this was partly bravado and partly a political attempt to ensure that as much of old Sinn Féin as possible remained onside.

Fianna Fáil was victorious in the 1932 general election and de Valera became taoiseach (prime minister), a post he was to retain for 16 years. In spite of fears of renewed warfare, a transfer of power between the two civil war belligerents had been accomplished constitutionally and peacefully. In the decade of fascism, in spite of sporadic low-level violence involving the residual IRA and a somewhat ineffectual fascist-type organisation, the Blueshirts, Ireland remained firmly a parliamentary democracy.

Éamon de Valera 1918–1921. Photo by National Photo Company Collection – Library of Congress Catalog from Wikimedia Commons

In the first part of the 1930s, elements of the rump IRA and republican movement (the military organisation, and in particular its ‘Army Council’, being of much greater weight than any political elements) veered towards leftwing positions, but in the latter half of the decade social activism came to be discouraged and renewed emphasis was placed on military action against the British to end the partition of Ireland. Some republicans flirted with corporatist and antisemitic attitudes at this time.

After 1939 the IRA became active in Britain again, attempting to sabotage the war effort and seeking support from Nazi Germany, even producing a plan to co-operate with it in an invasion of Northern Ireland. Meanwhile de Valera had, from the mid-1930s on, abandoned his former complaisance with regard to the organisation. When IRA activity was seen to threaten the Free State’s policy of military neutrality during the war, systematic repression was introduced, with suspected IRA members interned without trial and a small number executed for the murder of policemen.

Decimated by state repression North and South, the IRA had no more than a couple of hundred members left in the late 1940s. Attempting to resurrect militant republicanism, the organisation made two important decisions: first, it would henceforth direct all its activity against Northern Ireland and refrain from attacking agents of the southern state (which in 1948 had declared itself a republic); second it would complement military activity with propaganda. IRA members were instructed to join Sinn Féin, which had been languishing since Fianna Fáil’s entry into constitutional politics: the party went on to enjoy a very limited degree of electoral success North and South in the 1950s.

The military campaign, however, was ineffective: a small number of Northern Irish policemen were killed, but a greater number of IRA men died in the process. As before, the authorities moved ruthlessly against the movement, with internment without trial being introduced North and South. In 1962 the campaign was wound up. An IRA statement blamed the Irish people for its lack of support: ‘Foremost among the factors motivating this course of action has been the attitude of the general public whose minds have been deliberately distracted from the supreme issue facing the Irish people – the unity and freedom of Ireland.’

As long as the ending of partition was seen as ‘the supreme issue facing the Irish people’, it was of no great relevance whether militant republicans tended individually towards the left or the right, or indeed had no marked inclination towards either. Of two IRA volunteers killed in a botched raid on the border in Co Fermanagh in 1957, one, Fergal O’Hanlon, was a devout young Catholic who had recently been considering becoming a priest; the other, Seán South, was a Catholic intellectual who had, in a stream of letters to his local newspaper, praised Senator Joseph McCarthy, condemned trade unions and excoriated the Hollywood film industry for its ‘stream of insidious propaganda which proceeds from Judeo-Masonic controlled sources, and which warps and corrupts the minds of our youth’. The leader of the unit, Seán Garland, who, though injured himself, had carried the dying South away from the scene on his shoulders, was to become a Marxist during the 1960s and remained until his death in 2018 the most stubbornly orthodox of communists.

The next phase of development of the republican/IRA movement was to see leftwing ideas, rather than purely nationalist (or Catholic-nationalist) impulses come to predominate. But it also intersected, towards the end of the 1960s, with the latest flare-up in violence in Northern Ireland, that thirty-year conflict that is euphemistically known as ‘the Troubles’.

The mini-state of Northern Ireland was born in sectarian violence. About 460 people died in intercommunal clashes in Belfast in the early 1920s, the fatalities affecting disproportionately the Catholic minority in the city. The state had been constituted with borders designed to make it large enough to be viable but with a religious balance that seemed to promise a solid unionist/Protestant majority well into the future. It was to become, as one unionist leader later admitted, ‘a cold place for Catholics’, who were much more likely to be unemployed or to feel forced to emigrate. They also suffered from discrimination in access to public housing and, through the manipulation of electoral boundaries, in terms of political representation.

One area in which they were not significantly disadvantaged, however, was in access to education. By the later 1960s there had emerged in the Catholic community the germ of a new, confident and educated leadership whose perspectives were less simply nationalist (or anti-partitionist) and less sectarian or purely communalist than those of its political predecessors. This was the civil rights movement, a group which was able to mobilise large numbers of people in demonstrations and exercises in civil disobedience and which, in its tactics (and even in its anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome’) was strongly influenced by the movement for equal rights for African Americans in the US.

The civil rights movement’s leaders stressed that its aims were simply for civic equality in Northern Ireland, and that these aims would be pursued by wholly peaceful means. Nevertheless, the movement was perceived by the unionist establishment as a Trojan Horse for anti-partitionist republicanism and many demonstrations were dispersed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. This in turn led to street violence and, gradually, to the emergence of armed paramilitary violence. On the Protestant side, this was aimed at forcing Catholics ‘back into their box’ and on the Catholic side at ‘defending the community’ – and perhaps as a way of resurrecting IRA activity on a more solid basis and with more support than in the 1950s.

One immediate effect of the renewal and quick escalation of violence was a split in republicanism, with that element influenced by Marxist ideas soon repudiating ‘armed struggle’ in favour of social and political agitation and seeking to build unity with Protestant workers. Those who prioritised ‘defence of the community’ and a renewed military campaign against partition broke away, forming the Provisional IRA (and Provisional Sinn Féin as a parallel political organisation). The leftwing element was henceforth referred to militarily as the Official IRA (which soon became largely inactive) and politically as Official Sinn Féin, which contested elections and evolved over the years into Sinn Féin – the Workers’ Party and then The Workers’ Party. In the latter guise it enjoyed a significant measure of electoral success in the Republic of Ireland before breaking up into a democratic socialist party (Democratic Left) and a rump Marxist-Leninist element which retained the WP name. Democratic Left eventually merged with the Irish Labour Party.

The history of ‘the Troubles’ themselves is familiar enough not to have to be rehearsed in detail here. But some statistics may be useful. Something over three and a half thousand people died in the 30-year conflict, just over half of them civilians. Of those killed by republican paramilitaries (chiefly the Provisional IRA), about 1000 were members or former members of the security forces, but more than 700 were civilians. Of those killed by loyalist (Protestant) paramilitaries, 41 were republican paramilitaries, but almost 900 were civilians. It was a multi-sided conflict conducted by armed men, in which unarmed men (and women) were the main victims.

A British Army Technical Officer approaches a suspect device at the junction of Manor Street and Oldpark Road in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Photo by Snozzer from Wikimedia Commons

It is also worth saying something about how the conflict was perceived by its participants at the time, since this differs significantly from how it has often been portrayed in retrospect. The highest number of deaths were clustered in the early to mid-1970s – with 1576 fatalities between 1972 and 1976. Thereafter deaths fell considerably: from 1983 to 1998 (when the Troubles ended) they only once topped 100 annually. In its early days, the Provisional IRA was militarily quite effective and had considerable hopes that its campaign would be successful (leading to a quick British withdrawal and a united Ireland). In fact, 1972 had been designated ‘the year of victory’. There were 476 deaths that year, but there was no victory; rather, extending over years and years, a bloody stalemate.

The prospect of an end to this stalemate began to emerge in the early 1990s when the leader of constitutional nationalism in Northern Ireland, John Hume, began to engage with Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin to explore possible ways in which a ceasefire and a settlement might be brought about. This ‘peace process’ resulted, after long years, in the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

As Sinn Féin prepared its members and supporters for compromise, its rhetoric perceptibly changed. No longer was there talk of victory; instead it became a matter for celebration that the IRA (often euphemistically referred to as the ‘republican movement’) was retiring from the conflict ‘undefeated’. For those of younger generations who had not witnessed the worst years, a shorthand history of the Troubles was on offer: the war had been regrettable; it had been bloody; everyone had suffered; but it had been necessary to achieve the end result of justice and equal treatment for both communities now enshrined in the honourable compromise of the Belfast Agreement.

Many historians found this version difficult to buy into, pointing to the major victories won by the non-violent civil rights movement before ‘the war’ had started, when the British government in London had disowned and disempowered the local unionist regime in response to domestic and international pressure over its record of religious discrimination and misrule. From this perspective, thirty years of killing had brought no further significant political advance, at least nothing that had been worth dying for or killing for.

One result of the peace process was that, as republicans signalled their possible willingness – after a protracted game of cat and mouse – to purse their aims by peaceful means alone, Sinn Féin became more popular with the electorate, eventually surpassing the constitutional nationalists of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in the competition for votes in the Catholic community in the North. The party also made strides in the Republic, progressing from a 2.5% vote share in the last Dáil election before the Belfast Agreement (1997) to 24.5% in February this year (the highest share of any party).

It has long been a commonplace of the left in Ireland that there is no real political difference between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, that both are conservative, right-wing parties and there is no justification for their separate existence. In fact there have always been quite significant differences between them, both sociological and political. Fianna Fáil is more nationalist (and, being republican in its origins, has sometimes, on its fringes, been slightly soft on SF/IRA). It has traditionally had a more popular base, once proudly proclaiming itself ‘the party of the men in the open-necked shirts’, though in the latter part of the last century it moved closer to business, and particularly to the important construction industry.

Even in straitened circumstances, however, Fianna Fáil has tended to be more alive to the needs of the disadvantaged and, until recently, enjoyed significant support from the urban working class. Fine Gael, on the other hand, has traditionally received more support from the professional classes and all those who value caution, balancing the books and ‘fiscal rectitude’. Neither party, of course, is socialist, but then the organised working class has not been a huge feature of the history of the southern state (the northeast, and in particular Belfast, having been traditionally much more industrial).

The economic collapse which hit Ireland particularly hard after 2008 had the effect of almost destroying the two parties then in government (Fianna Fáil and the Greens) in the election which followed in 2011: Fianna Fáil lost 51 seats and the Greens all six of theirs. Into the breach, to form a coalition government with Fine Gael, stepped the Labour Party, with 37 seats (up 17). This government, which ran from 2011 to 2016, made considerable progress towards restoring Ireland’s economic fortunes: unemployment fell from 14.5% when it took office to 8.4% when it left. But the austerity measures implemented early in its term cost both parties dearly. In the 2016 election Fine Gael lost 16 seats and Labour 26, while Fianna Fáil rebounded to a degree from its 2011 floor.

Irish politics seem to be in a state of considerable volatility, of which the main beneficiary is Sinn Féin, which has the ability to appeal to Fianna Fáil’s and Labour’s traditional electorates on the basis both of traditional republicanism and populist appeal, while also gaining favour with younger elements of the electorate for its strongly-voiced positions on worsening social problems like the lack of affordable housing to buy or rent – perhaps the single most important issue in this year’s election.

Volatility can cut both ways, however: in May 2019 Sinn Féin lost half its local council seats (159 dropping to 81) and two out of three of its European Parliament seats. So its spectacular success less than a year later was not – until late in the election campaign – greatly expected. What has been lost, it seems, can be won back again; and what is won lost. The party’s immediate prospects, however, seem fairly bright. One thing, however, stands in the way of its route to power.

Why was it that no other significant group – with the probable exception of the Trotskyist left – was keen to facilitate Sinn Féin’s participation in government? The chief reason is that politicians, who generally have longer memories than the voting public, do not trust it. For thirty years Sinn Féin and its military organisation prosecuted a war in Northern Ireland whose aim was to force the majority community in that territory to accept incorporation into a united Ireland against its will. Mainstream republicanism never accepted that the Northern Protestant/unionist community had any right to reject unification, for which it was pointed out there was a majority on the island.

The compromise involved in the Belfast Agreement was that unionists would afford a guaranteed place in shared government in Northern Ireland to nationalists (effectively to Sinn Féin), and that republicans, North and South, would agree that there could be no constitutional change without majority consent in the North (as well as in the Republic). This was an unprecedented, almost heretical, concession, but republicans were perhaps able to look on it with some equanimity in the light of the considerable demographic shift within Northern Ireland: when the state was founded 100 years ago Protestants constituted a 65% majority; within the next decade they are likely to become a minority.

Sinn Féin leaders carry the coffin of Martin McGuinness in 2017. Photo by Sinn Féin. Flickr from Wikimedia Commons

Theobald Wolfe Tone defined his creed as having two essential components: breaking the connection with England and uniting ‘the whole people of Ireland’ irrespective of their religious affiliation or ethnic background. But Sinn Féin’s policy with regard to Northern Protestants since it signed up to the Belfast Agreement has been less one of ‘reaching out’ or conciliation than of implementing a strategy of tension. Indeed, one might say that for Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, politics boils down to the continuation of war by other means: since no meaningful compromise can be reached with the Protestants, one might as well proceed as quickly as possible with measures to defeat them. This currently takes the form of pressing for an early referendum on Irish reunification, a strategy which many regard as potentially dangerous: might elements within a community that feels itself cornered return to violence?

However, Sinn Féin’s policies and actions in the North do not necessarily impact hugely in the South, where there often seems little interest in what is going on 100 kilometres away. Election results indicate that during the course of the conflict, only a small proportion of the population in the Republic, certainly well below 5%, approved of what the IRA was doing in the North. After violence ceased, support for Sinn Féin increased. It is currently particularly high among that section of the population that has no personal memory of the Troubles.

The question has often been posed as to why there is no far-right populist party in Ireland. The answer is that the ground is already occupied by Sinn Féin. This does not mean that Sinn Féin is a far-right party. It patently is not. But much of its support over recent years (until this dramatically expanded again in 2020) has been among sections of the population whose counterparts in other countries often now vote for the populist right. It has certainly won approval as the ‘anti-system’ party; in many working class areas Sinn Féin representatives are admired as being ‘just like us’, while politicians from the other parties are vilified as ‘robbers in suits’. Sinn Féin has won this popular support without indulging anti-foreigner or racist sentiment, and while espousing redistributionist social policies which by any objective criteria must be regarded as leftwing – and indeed, in the lead-up to this year’s election, doing so with more conviction than the parties of the traditional democratic left.

What prevents it from being seen by other parties as entirely respectable (fréquentable as the French and Belgians say) is its failure – and unwillingness – to deal with its past. When the Sinn Féin deputy for Waterford, David Cullinane, was re-elected in February, a video was circulated showing him ending his victory speech by shouting pro-IRA slogans. A veteran journalist, Fergal Keane, wondered if Cullinane himself had ever ‘heard a shot fired in anger, or stood amid the gore of a bombing, or if he has seen the mess a high-velocity round makes of the human head’.1 It is unlikely that he had. But in another constituency where the re-election of the Sinn Féin deputy was accompanied by the singing of IRA songs, the connection was closer. Dessie Ellis, a long-time deputy for the Dublin North-West constituency, was sentenced to ten years in the 1980s for possession of timing devices to be used in bombs – which throughout the course of the Troubles did indeed produce a lot of human gore.

It may be that Sinn Féin is now ‘a slightly constitutional’ party, or even a more than slightly constitutional one. Few people expect to see the IRA returning to violence, though in a possible situation of greatly increased tensions between the communities in Northern Ireland, exacerbated by Brexit, nothing is impossible. Some commentators have speculated that the party will eventually become respectable at the end of one more electoral cycle. In the meantime, most of its political competitors still feel that it is not quite a party like any other: its considerable financial resources, large full-time staff and extensive property portfolio, dwarfing the capacities of its rivals, may be one reason for this.

Those who seek to deny Sinn Féin the label of ‘left’ are not always on strong ground. Its MEP is a member of European United Left/Nordic Green Left in the European Parliament, alongside representatives of Syriza, Podemos, La France Insoumise and Die Linke. Its current policies are certainly vigorously redistributive and if it is still found deficient in its commitment to the strict democratic spirit, that has also been the case over the last hundred years for other leftwing movements.

But there are also other questions: is the republican movement’s near total lack of interest in engaging with Northern Protestants compatible with the universalist leftwing tradition based on Enlightenment values (and exemplified by Tone), a tradition where people are not Protestant or Catholic but just people? And what indeed is the party’s main focus? Is it social equality and the fight for a greater share of resources and opportunity for the working class? Or is it still, as formulated in the IRA statement of 1962, ‘the supreme issue facing the Irish people – the unity and freedom of Ireland’, with success in electoral politics chiefly seen as a means to achieving that end?

Ireland’s next government looks likely to be formed by an unprecedented alliance between the Civil War parties, with additional support from either the Greens or, if no deal is struck there, a number of Independents. In this scenario, the left would have what it has long dreamed of: the ‘two rightwing parties’ (perhaps today more accurately characterised as a centre-right and a centrist party) coming together and leaving a ‘representation gap’ for the opposition to grow in. Not just Sinn Féin but the small democratic socialist parties would hope to benefit from this.

In the short term, the coronavirus crisis seems to be politically benefiting the party in power: a poll late last month showed a sharp 13% rise in support for Fine Gael from its general election figures. In the middle and longer term, however, the measures that the next government will be forced to introduce in order to restore public finances could see it rapidly losing popularity. By some distance the best-organised and best-financed party in the state, Sinn Féin can reasonably look forward to growing further in opposition over the life of the next government – particularly if the Greens are part of the new government. The chief possible threat to its further progress could be its apparent continuing existential fixation on ‘the supreme issue’.

Enda O’Doherty worked before his retirement as an editor for ‘The Irish Times’, chiefly on international news. He is joint founder and co-editor of the ‘Dublin Review of Books’ and is writing here in a personal capacity.

Fergal Keane, ‘“Up the Ra”: David Cullinane never stood amid the gore of a bombing’, Irish Times 17 March 2020, online at: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/up-the-ra-david-cullinane-never-stood-amid-the-gore-of-a-bombing-1.4204429

Published 18 May 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Enda O’Doherty

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Two opposing interpretations of 1945 form the ideological core of today’s confrontation between Russia and the states of central and eastern Europe. Both are reactions to the collapse of the Cold War order.

Controversies over the legacies of dictatorship and civil war have polarized the Spanish debate for over two decades. Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of Franco’s death, the legitimacy of the transition is uncertain. Could things have been done differently?