The city of Donetsk’s call for independence from Ukraine is a pivotal issue in war-torn Donbas. Its role as regional centre, at the core of the Donbas Coal Basin, upholds its weighty position. But environmental protests in Mariupol, says Yulia Abibok, show how local identity is split, perhaps irrevocably.

In Ukraine, regional identity was once considered the strongest in the Donbas. However, since 2014, ongoing unrest has revealed a divide amongst various Donbas communities. In a recent study on local identities within what is left of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, collectively known as the Donbas, I have been asking whether this area should and could be divided between its neighbours. While the research is still ongoing, what I’ve seen so far indicates that only the city of Mariupol within the Donetsk region has its own strong and well-developed identity. To understand why this might be the case and what it might indicate politically for the war-torn area, both contemporary and historic factors need to be taken into account.

Analyzing local news feeds and, where possible, forum posts, I’ve discovered that certain communities, namely Pokrovsk and Bakhmut in the west and northeast of the region respectively, still see themselves as part of the Donbas. And while this is natural for Pokrovsk, which is prized for its resource of coal mines and is surrounded by other coal mining towns, the Bakhmut discovery is rather surprising.

There are those from Maripoul, the second biggest city in southeastern Ukraine, who say that it was at the centre of the county during the Russian Empire when the neighbouring city of Donetsk was just a steppe. But, in fact, it was Bakhmut that was at the county’s centre to which the settlement of Yuzovka, now Donetsk, belonged. For a short period of time after the Bolshevik revolution, Bakhmut was also a regional centre, until Yuzovka, later renamed Stalin, finally took its official status. Nevertheless, I have not yet found any strong statements from Bakhmut that suggest Donetsk’s position is considered a historical injustice.

For Bakhmut residents, the groundbreaking 2014 revolution was either about remaining within Ukraine or participating in establishing the Donetsk ‘Republic’ with the possibility of joining Russia. It was not a question of its status as a community.

At the beginning of 2014, the local newspaper Sobytia speculated about the threat from Euromaidan activists and Soviet-era forced resettlers from western Ukraine to villages right outside the city. Across the entire region, rumours, which led to panic about uninvited guests from the west of Ukraine arriving in respective cities en masse to topple local Soviet statues, mobilized the masses. Although no one had cared about the statues before, the fear of symbolic humiliation made people take to the streets to protect their contentious Lenins.

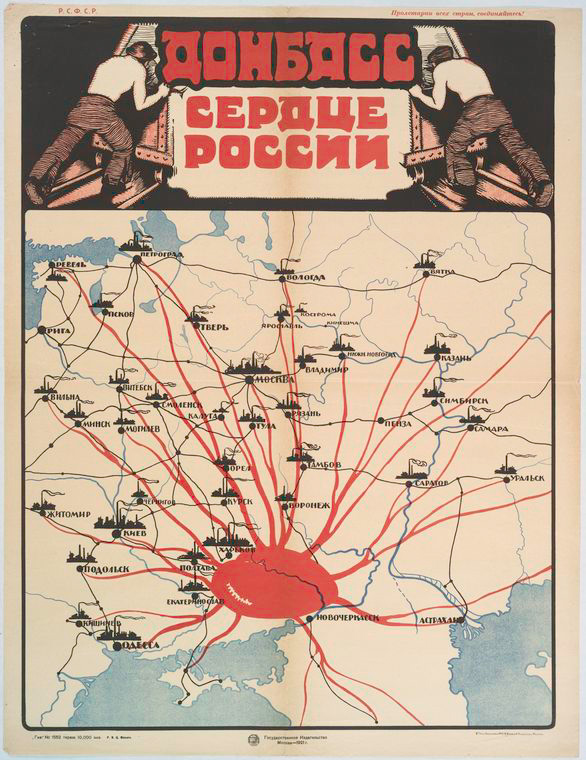

‘Donbass – the heart of Russia’, as depicted on an early Soviet poster from 1921. Photo via New York Public Library’s Digital Library via Wikimedia Commons.

While there was still some discontent, no one protested against the removal of the very same statues in 2015 and 2016 during decommunization. And little attention was paid to renaming the cities. In 2016, when Bakhmut was renamed with its historic rather than Soviet name of Artemivsk, Sobytia stated, that ‘The single thing which is not clear is where to accent: BAkhmut or BakhmUt?’

Historical legacies

When Donetsk is referred to as Yuzovka, its nineteenth century name is used to portray the massive city as a settlement inhabited by bandits and thugs from all over the former Russian Empire. Many people, especially those from neighbouring Mariupol, see Donetsk as a historical anomaly; indeed, strong rivalry has existed between the two cities for decades. While Donetsk’s pre-2014 establishment claimed that the region had been creating income for the entire country, many people from outside the city felt they had been financing the municipality and getting nothing in return.

Before the industrial revolution during the Russian Empire, the Donbas was a land of warriors and merchants. If there had been no coal (the ‘black gold’ of imperial and Soviet regimes), its present day would be completely different – maybe not well off but possibly happier.

Donetsk metallurgical plant. Photo by Andrew Butko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons..

Having developed around a steel plant in the second half of the nineteenth century, which expanded to include neighbouring mining towns in the first half of the twentieth century, the city of Donetsk became the region’s railway crossroads delivering coal and steel throughout the empire, including to the port at Mariupol. For Russian intellectuals at the time, the city became ‘the new America’ because of its industrial strength and diverse population.

After its 1960-70s ‘golden’ era, Donetsk started to become a southeastern political monster. This role proved fatal in the early 1990s when local miner strikes toppled the Kyiv central government, in the early 2000s when Donetsk elites attempted to steal the country’s presidency and caused the Orange Revolution, and in 2014 when the city became an epi-centre of a pro-Russian uprising which paradoxically put an end to Donetsk’s own political and economic domination.

2014 and its aftermath

The Donetsk Coal Basin still dominates southeast Ukraine. However, the basin does not span the entirety of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. There are no coal reserves and, therefore, no coal mines in the south of the Donetsk region and in the north of Luhansk. Some residents of these areas were quick to seize the opportunity to distance themselves from the terror of the ‘Russian spring’ whose frontline had isolated the regions’ core from the rest of Ukraine.

Just as pro-Russian separatists were conducting a ‘referendum’ about independent Donetsk and Luhansk ‘Republics’ with the promise of their annexation to Russia, a parodic referendum in the west of the Donetsk region aimed at joining the neighbouring region of Dnipropetrovsk. Rumours began spreading in some cities that locals were being newly registered in neighbouring regions, which authorities denied. And, although disinformation was pivotal here, people discussing the very idea of changing their regional allegiance was the more significant factor.

There is a stereotype in Ukraine that the southeast is resistant to democratic change. In the early 1990s, many locals still considered themselves as ‘Soviet people’ and voted for communists. They used to elect the pro-Russian Party of Regions (PR) and were very unlikely to vote for any other party.

From the other side, no one tried very hard. Other parties did not invest in the Donbas because it was widely regarded as a PR stronghold. Local leaders were often forced to join the PR as the only way to receive much-needed state subsidies, which were selectively allotted based on political loyalty. The Luhansk region’s rural north was the only area where the absence of big industrial entities, whose owners are strongly affiliated with the PR, meant some political diversity.

Even after 2014, local voters tended to choose what was left of the Party of Regions. As the area has never been entirely considered part of Ukraine, not many people in Kyiv knew what to do with it after the destruction of local political and business ‘clans’. And, more importantly, few wanted to try. In 2015, Anatoly Tkachuk, one of the major initiators of the Ukrainian decentralization reforms, wrote a plan dividing what was left of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions between their neighbours, but, as he told me, no one in the government was interested.

Transport connections within the southeastern regions have ceased to function properly due to war damage. You now need about eight hours to reach Mariupol from Kramatorsk in the Donetsk region, which is more than if you wanted to reach Kyiv. And, as for Mariupol, which is half-encircled by the frontline and the Azov seashore, the nearest regional centre is not Kramatorsk within the Donetsk region but Zaporizhia.

Another industrial legacy under pressure

0629.com.ua is an independent news site in Mariupol whose feed already looked like a military communique in 2012. At least several days a week, the website had been warning about ‘unfavourable weather conditions’, recommending that people close their windows, do not walk outside, drink more water to reduce intoxication or leave the city for a day or two.

The air and sea of half a million Mariupol residents are polluted by the city’s two large steel plants. Emissions from both the Illich Steel Plant, which was constructed in the late nineteenth century, and Azovstal, built during Stalin’s regime, have been significantly reduced during post-communism, but their modernization is not yet complete. If there is no breeze in the city, you breathe nothing but emissions.

Ecological demonstration in Mariupol, Ukraine against environment pollution. Photo by ©Hurricanehank via Dreamstime.com.

By 2012, both plants belonged to Rinat Akhmetov from Donetsk, Ukraine’s richest man and most prominent supporter and member of the PR. Mariupol’s disagreement with Donetsk had already been aggravated in 2010 when the Illich Plant, which contributes heavily to the city’s budget and was a society within a society with its own network of shops, pharmacies, farms and even a football club, was forcibly put on sale and bought by Akhmetov.

Several dozens of locals first took to the streets in early 2012 to demand that emissions be reduced. They gathered again and again until in the end thousands were protesting under the slogan ‘Mariupol is not Donbas, eco-horror is not for us’. It became impossible for the local authorities and the plants’ management to ignore them. By the end of the year, the 0629.com.ua website had launched an online poll under the headline ‘Mariupol is not Donbas. And this should be confirmed officially’ with 60% of participants voting in favour.

The idea of establishing a new, separate Priazovia region with Mariupol at its centre has long existed and events in 2014 provided its supporters with a new opportunity. Like most cities and towns in the region, Mariupol was soon seized by pro-Russian rebels after several bloody clashes occurred in the city. The Russian spring saw minor local resistance there. Ahkmetov organized worker patrols in Mariupol to try and restore order to what was left of his empire. These actions had a symbolic meaning, as order was later restored to the city by Ukrainian military volunteers. For those with an anti-Donetsk stance, the frontline just behind the city became the reason to stand firm with their community as ‘Ukrainian patriots’ against Donetsk.

Heated discussions about Mariupol’s future administrative status took place that same year. As one local web forum participant stated, ‘We want to live in our homes in Priazovia and not in Donbas. Let “Downbas”1 solve its own problems. All they are able to do is cause incidents in the city. My entire life, there have only been troubles because of Donetsk in Mariupol. And they have thrust a war upon us.’ Some insisted that they would like to change Mariupol’s administrative allegiance because they felt ashamed of being part of the Donbas.

Meanwhile, others saw the war as an opportunity. As Mariupol is the second largest city in the southeast after Donetsk, regional institutions were re-registered there in autumn 2014. Suddenly, the Mariupol community was satisfied that their city had become ‘Donbas’s official capital’. However, this hiatus did not last long: that same year, most institutions were moved once again somewhere closer to the geographic centre of the region, mainly to the much smaller city of Kramatorsk.

Mariupol was quick to take its new position as ‘the last stronghold’ of Ukraine in the southeast. Donetsk oligarchs began investing heavily in Mariupol instead of Donetsk, which has significantly changed the city. One forum user reacted to a message about new investment into local infrastructure, saying ‘without Donetsk, Mariupol is starting to look like a city’.

Coal-mining spoil tips along the Kalmius river in Donetsk. Photo by Andrew Butko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The regions’ future

Some in Mariupol still see their chance for administrative satisfaction in this situation of general indifference. In early 2019, a petition was published on the Ukrainian president’s website that completely ignored Kramatorsk as the regional centre and proposed stripping Donetsk of the same status in favour of Mariupol because ‘administration and inhabitants of this city have demonstrated infidelity towards the Ukrainian state and sided with Russian occupants. In contrast, Mariupol inhabitants have stood with the independent Ukrainian state and taken an active part in its defence from the Russian occupation’. Only 310 people of the 25,000 required supported the petition.

I could be insulted by the wording as a Donetsk inhabitant, but, as an observer, I admire their assertiveness.

The socio-political allegiances and identities of local communities throughout the Donbas are complex. Responses to full-scale decommunization provide just one indication of southeast Ukraine’s split position. When the names of many local streets were changed, the central governmental decision enraged locals. Although the authorities did not usually insist on exact names, people were particularly angry because changes were seen as post-revolutionary. Meanwhile, the decentralization reform, which has stripped many villages and towns of their own authority, was taken positively or neutrally, as it provided additional funding and administrative power to larger communities.

In other words, everything is a matter of approach. And, as I doubt that there are many chances to transform the debris of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions into something well-functioning and prosperous, it may be preferable to reintegrate local communities somewhere else if their distinct identities appear stronger than the common Donbas identity.

The comment is a derogatory reference to those with Down syndrome.

Published 17 December 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Yulia Abibok / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

For those who suffered the consequences of Yalta’s division of Europe, the Helsinki Final Act brought grounds for optimism. Today, as Russia’s regressive war on Ukraine reopens old conflicts, it stands as a monument to European modernity.

Artist Marharyta Polovinko’s creativity persisted in a tormented form through her experiences as a soldier on the Ukrainian frontline. The words of a recently called-up fellow creative and young family man provide a stark reminder that the Ukrainian military is buying Europeans time.