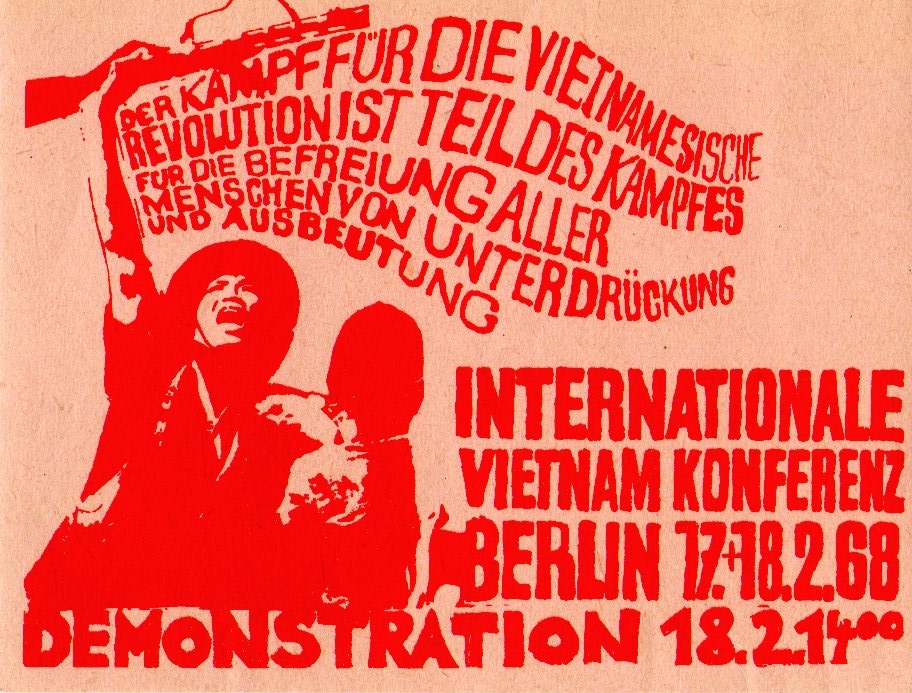

February 1968. Radical leftists from all over the world are in West Berlin to attend the International Vietnam Congress. The main auditorium of the Technical University is packed to the rafters. A banner has been draped over the edge of the viewing balcony demanding the ‘liberation of all people from oppression and exploitation’. Hanging next to it is the resplendent image of Ho Chi Minh. The Tet offensive has just demonstrated the vulnerability of the US military in Southeast Asia and an American defeat has become a real possibility. Among those attending the conference is the little known French anarchist, Daniel Cohn-Bendit. The main attraction, however, is Rudi Dutschke, the charismatic leader of the Socialist German Student League (SDS). Dutschke delivers his speeches with deep pathos and is fond of citing Marx’s mantra about ‘the categorical imperative to overthrow all relations in which man is a debased, enslaved, forsaken, despicable being’. ‘Comrades! We don’t have much time!’ he exclaims on the second day. ‘Every day, we too are being crushed in Vietnam, and not just figuratively speaking.’ At this very moment, Dutschke is vacillating between giving up the fight or becoming a ‘real’ urban guerrilla. Shortly afterwards, he is vilified for appearing on the cover of the magazine Capital for a thousand deutschmarks. Then, in April, he is shot three times by a neo-Nazi on the Kurfürstendamm.

What does this breathless, desperate political existentialism have to do with this year’s polished retrospectives of 1968? How did the socialist impetus for the Vietnam Congress, with its identification with the workers’ movement, relate to other arenas of revolt? To the university, for example – the home of the students and the starting point of the revolts, which was supposed to be transformed into a ‘critical university’? To the global pop-cultural movement, the subculture that drove the youth revolt? Or to the women’s movement, which put sexual equality on the agenda once and for all. ‘We students’, ‘we young people’, ‘we women’ – how did these collective identity-markers relate to the ’68ers’ committed anti-capitalism and utopian socialism? What remained of this socialist impetus in later decades and what remains relevant today?

The instigators of the revolt understood themselves as social revolutionaries. They wanted to overcome ‘late capitalism’, which they believed could not be reformed, and build a free society. In part, this emulated ‘real socialism’ and in part was clearly at odds with it. As to what the adjective ‘socialist’ might mean, they had no concrete idea. As with many of their ideological precursors, not least Marx, there was little relation between the ferocity of the critique and the clarity of the alternative. The socialist ’68ers were primarily anti-capitalists, counting on a dynamic emerging from the class struggle; specific questions about how the ‘new society’ was to be organized were saved for later.

Western Europe in the 1950s was characterized by latent class distinctions and hard class conflicts. During the Wirtschaftswunder, Les Trente Glorieuses and the era of the ‘affluent society’, an elevator effect took place that lifted all classes equally (without closing the distances between them), a process driven by Keynesian economics and industrial relations. In the course of this process of ‘domestication’, critique of capitalism became critique of consumerism, although rarely of the exploitation of nature. Ten years later, perceptions of capitalism were shaped by neoliberal ideologies holding that individuals were responsible for their own predicament and that there was ‘no such thing as society’. Capitalism’s predisposition towards crisis had in no way been overcome.

After 1968, some of its protagonists went into the factories in the hope of mobilizing the workers to join a mass uprising. After the strikes in France in 1968, however, that succeeded sporadically at best. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the ‘subjective factor’ together with all the joy of self-experimentation that had gone with it were replaced by the ‘revolutionary subject’ of historical progress.

Identity politics versus class struggle?

As to how 1968 influenced developments in Europe, one can begin with its achievements in the sphere of ‘reproduction’: higher education reforms have led to more educational equity, if not to the ideals of the ‘critical university’; cultural plurality and the legitimacy of subcultural minorities are now widely if not universally accepted; sexual equality has largely been realized, albeit within limits – as the #MeToo debate and continuing discrepancies in status and earnings show. An antifascist though not always anti-totalitarian consensus has been established and the commemoration of Nazi crimes has been institutionalized. Internationalism has broadened the political horizons of postcolonial Europe, which since the 1970s has increasingly been confronted with immigration from the non-European periphery. Children’s rights have been written into constitutions, same-sex marriage has been allowed, and bans on cannabis have been lifted. The French would call this globalement positif. And indeed, these things can certainly be seen as democratic progress.

But what has become of anti-capitalism? Awareness of social inequality has increased, but that hasn’t stopped inequality growing since the 1990s. The overall balance is mixed. On the plus side, the ’68ers have played a major role in the democratization of western societies, contributing to the revolution in participatory politics during the ’70s and the emergence of an assertive civil society throughout Europe, even in the East after 1989. Many of the fiercest anti-capitalists, above all the ‘salon Maoists’, became staunch liberals – to the chagrin of an implacable part of the Left that still claims to be the sole legitimate heir of 1968.

This middle road of ‘fundamental liberalization’ (Jürgen Habermas) is today disputed from two sides. The radical Left dogmatically insists on maintaining the protest movement, as if its revolutionary impetus could simply be kick-started. Meanwhile, a revisionist anti-’68 position is gaining ground that attempts to reverse the identity politics supposedly introduced by the New Left. It is this that lends the New Right its ideology: social Darwinism instead of solidarity, patriarchy instead of sexual equality, plebiscitary populism instead of democracy, historical whitewashing instead of commemoration, ethnic nationalism instead of multi-ethnic republicanism. The ‘spiritual and moral turn’ announced by Helmut Kohl in the 1980s and the neoconservative opposition to the ‘culture wars’ in America now goes under the name of ‘conservative revolution’. As it says on the packet: counter-revolution is the goal.

But 1968 wasn’t just about identity politics. Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello have described the revolt as ‘artistic critique’ as opposed to the social critique of the workers’ movement. While the cause of poverty and inequality is capitalism, the ’68ers tended to fight against normativity. With their insistence on values like autonomy, spontaneity, mobility, flexibility and creativity, the ’68ers actually served the ‘new spirit of capitalism’ – just as the Protestant work ethic once served industrial capitalism. Only ten years later, Régis Debray, a companion of Che Guevara, levelled a similar accusation at the May Uprising of 1968.

The gulf between top and bottom, rich and poor, capital and work has indeed grown in recent decades. Yet the differences between women and men, gay and straight, black and white remain no less relevant. All too often, disadvantages of race, class and gender merge. Even if identity politics has at times been taken to sectarian extremes, the value of sensitivity to cultural difference remains undiminished. Moreover, it is not necessarily a bad thing that the critique of consumer capitalism has widened. Alongside exploitation, which can apply to precarious workers such as couriers, cleaners and carers, as well as to internet professionals on zero-hours contracts, it now includes unfair trade, dangerous emissions and products that damage health. At the same time, the task of a contemporary Left is still to oppose discrimination, to campaign for social solidarity, and to represent the ‘humiliated and insulted’, as Dutschke put it back then, citing Marx and Dostoevsky.

More than twenty years ago, Richard Rorty warned that the workers, whether organized or not, would one day take revenge upon their rulers for doing nothing about loan-dumping and industrial outsourcing. Together with a middle class threatened with status loss, Rorty predicted, they would look for a strong leader and turn against politicians, lawyers, stock brokers, journalists and professors. All the prejudices against Blacks and Hispanics, women and homosexuals would then resurface. Donald Trump, who personifies all of this, should have come as no surprise.

The US historian Mark Lilla is Rorty’s controversial successor. Lilla calls for an end to an ‘identity liberalism’ that merely celebrates differences. This obsession with ‘diversity’, he argues, has encouraged rural and religious whites in the US to perceive themselves as disadvantaged, as foreigners in their own land, existentially threatened and ignored by the elites. Liberals, according to Lilla, should return to questions about class, the economy and the ‘common good’. What we need is a non-partisan politics that places less emphasis on differences and more on commonalities. Rorty called this ‘inclusive patriotism’.

Yet the critique of identity politics is only partially confirmed by the American presidential election. Donald Trump was not voted for by the majority of workers, or even predominantly by them. Actually, he received most support from the white middle class: people with an income of around 100,000 dollars per year. Far-right politicians across Europe all capitalize on the sentiment of what, more than eighty years ago, the German sociologist Theodor Geiger aptly described as ‘middle-class panic’. Nevertheless, millions of white working-class voters with low levels of education, half of whom were women, did vote for Trump – despite his open sexism or precisely because of it. Trump’s no less open racism mobilized both groups even more.

Trump adopted the rhetoric of anti-capitalism and class struggle not to attack unscrupulous deal-makers or Wall Street brokers, of course, but women, minorities and the disadvantaged. If identity was decisive for his election victory, then that ‘identity’ was purely Anglo-American, fundamentalist Protestant or radical Catholic or Christian-Zionist. In a word: heterophobic. If it was class struggle, then it was one founded on an aggressive white-maleness, rather like anti-Semitism is said to be the socialism of fools. The identitarian critique of the inclusive and egalitarian identity politics of the New Left ends up as a defence of white male privilege.

In 2017, the Front National became the strongest political party in France, despite its sectarian origins and the long period of antifascist quarantine. In the 2012 presidential election, one third of all unskilled and skilled workers and the unemployed voted for Marine Le Pen. Today, the polls show that the party has a solid basis in a workforce that thirty years ago could be relied on to support the Left. Deindustrialization and the deregulation of employment have contributed to this travesty of anti-capitalism just as much as the virulent xenophobia that has always existed in this milieu. Didier Eribon’s memoir Returning to Reims describes this well, albeit in the context of an anti-liberal, gauchiste polemic.

Let it be emphasized: no social scenario, however desolate, justifies abuse of or discrimination against minorities. Nor, however, does the mere affirmation of cultural diversity, together with politically correct language, remedy deleterious social and employment conditions, which are again affecting women and minorities disproportionately. One has to keep an eye on both things – there are no major and minor contradictions, as Marxism-Leninism once saw it. Sexism and racism are one side of the story, the voters who defect to the far-Right because for decades they have not felt represented by established parties are the other.

There can be no alternative between collective identity and class, between artistic and social critique, between equality and difference, between universalism and particularism. An ambitious politico-social movement must consider both strands in combination. Capitalism is more than an economic subsystem. As Karl Polanyi argued some seventy years ago, it is a mode of socialization that posits difference as inevitable. Today, not for the first time, it blames inequality and exploitation on those whom they affect.

No socialism is not the answer!

Recovering from the shock of Trump means acknowledging oppression on the grounds of race, class and gender. The sociologist Göran Therborn asks a pertinent question: why are rich societies so much more successful in minimizing unequal treatment of specific groups than in minimizing the unequal distribution of income and wealth? Apartheid and the criminalization of homosexuality were defeated, differences between men’s and women’s incomes have shrunk, a black middle class has emerged in the United States. Yet race, gender and class remain central factors in the generation and reproduction of social inequality. That is why identity politics does not necessarily undermine opposition to income and wealth inequality. Nevertheless, it is also true that ‘those who care exclusively about “identities” aim to place everybody on the same starting line but do not care that some come to the starting line with Ferraris and others with bicycles.’

Overthrowing ‘all relations in which man is a debased, enslaved, forsaken, despicable being’ remains the categorical imperative. In various schools of thought, undogmatic Marxism included, there has been a welcome return to class. Marx the author is also enjoying a renaissance. This doesn’t mean a straightforward return to orthodox class struggle, nor to industrial relations as done until the 1980s. Low growth rates, the privatization of public services, the disappearance of traditional industrial sectors, social austerity and technology driven inequality have consigned the ‘elevator effect’ described by Ulrich Beck and others in the 1980s to the past. Restrictions on social rights have caused the prestige once attached to work to disappear, while the notorious one per cent has freed itself of the meritocratic illusion altogether.

As a result, questions of recognition have become more important. Today, we are seeing a new emphasis on moral categories like respect, dignity and visibility, whose flipside is diffuse anger, grievance and sheer panic. Ethno-authoritarian nationalists invoke solidarity amongst themselves while complaining that minorities do the same in self-defence. This is where the socialist critique of globalization urgently needs to set itself apart from the far-right variety. This is something that populists on the Left often overlook. Ethno-nationalism recognizes neither the compatibility of the problems facing workers and the unemployed in southern Europe and the Arab world, let alone in Africa, nor the existence of a common cause between westerners and the minorities queuing to enter what is still the exceedingly rich world of the OECD.

Finally, the object of critique – capitalism – has changed. Driven by finance, its centre of power now lies with the digital media monopolies. An ever greater share of wealth is created through a combination of speculative finance, property ownership and the increasingly kleptocratic extraction of natural resources. Capitalism has in many ways regressed to pre-industrial, neo-feudal forms of exploitation. Re-reading Das Kapital won’t be enough.

Organized labour no longer reaches those most hit by social inequality and injustice. This goes for the urban centres as well as for the capitalist periphery, which today – irony of history – is completely in thrall to Chinese state capitalism. A paradoxical result of 1968 was the collapse of social democracy and the democratic Left as a whole. Initially, it seemed that the opposite would be the case: social democrats came to power first in Germany and then, after some delay, in France. In Paris, this even took the form of a coalition with a revisionist Communist Party. Yet, as Ralf Dahrendorf predicted, the social democratic century had ended by the mid-1970s. The democratic Left had no effective defence against neoconservative ideology and neoliberal social experiments. Nor was it able to adopt the ecological critique, itself a development of the critique of consumer capitalism, made by New Left thinkers like André Gorz and the new social movements against nuclear energy and environmental destruction.

The ’68ers can be charged with – if not blamed for – having two major blind spots: Europe and the ecological question. Michel Rocard, Francois Mitterrand’s socialist prime minister from 1988 to 1991, was the first to consider the European Union as something more than an exercise in multinational capitalism. He argued that socialism either had to be European or not at all. When it came to ecology, the ’68ers were so utterly spellbound by industrial modernity and the class struggle that environmentalism and doubts about nuclear energy were alien to them. They didn’t yet know about climate change and forest dieback.

Any contemporary politics that wishes to engage with the New Left will have to confront this uncomfortable fact. It’s something that the ’68ers have in common with the wider political environment, whether conservative, social democratic or Eurocommunist: the belief in infinite growth and the opportunity it provided for social progress through redistribution. The new social movements that grew out of 1968 took their leave of this premise after entering the post-industrial age. This was connected to a political realism that provided a wing of the German Green Party with its name. Numerous ’68ers were active in it and indeed used it to further their ambitions. There is nothing necessarily reprehensible about that. However, it is a failing of the Left today that it is unable to counter the politics of ‘no alternative’ with social utopias able to motivate and mobilize younger generations. Soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible!