What happens to democracy when governments court the rich and highly skilled, offering citizenship as privilege, when those in need are turned away? This year’s Speech to Europe takes the concept of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ migrants to task.

João Cabral de Melo Neto’s 1955 verse drama ‘Death and Life of Severino’ accompanies Brazilian migrants in Portugal. Having fled violent crime, they seek freedom yet commonly find a life of servitude and institutional violence, where only art provides solace from poverty and hunger.

We are many Severinos

and our destiny’s the same:

to soften up these stones

by sweating over them,

trying to bring to life

a dead and deader land,

to try to wrest a farm

out of burnt-over land.

But, so that Your Excellencies

can recognise me better

and be able to follow better

the story of my life,

I’ll be the Severino

you’ll now see emigrate.

The Death and Life of a Severino, João Cabral de Melo Neto, 1955 (Translation by Elizabeth Bishop)

It was a Sunday in March and winter was beginning its slow farewell. The day dawned blue and turned grey. A whole six months living in Lisbon has taught me not to be surprised by this phenomenon. It had been six straight days of hard graft and, as with most catering workers, I started my one day off by putting my dirty clothes in the wash and taking the opportunity to tidy up my room. The sunshine thrilled me because it would both save me the expense of going to the launderette and save time.

I left the house, walked for just under 10 minutes and arrived at the Fonte Luminosa (luminous fountain). It is neither well lit nor well maintained, but it still trumps Rome’s Trevi Fountain. By now the day was grey and heralded the rain that would come that evening; I should have gone to the launderette, I thought. I walked along Alameda Dom Afonso Henrique, named after the first king of Portugal.

I soon spotted the modernist building that has caught my eye since I first set foot there. A symbol of Estado Novo architecture in Portugal, it opened in 1955 as the Império cinema-theatre, the same year that the book Morte e Vida Severina (The Death and Life of a Severino) was written in Brazil. During the 1980s it was vacated and remained so until it was bought by the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in the year of my birth, 1992. With the ‘Now Showing’ billboards long gone, every day at the top of the building there is a simple reminder to passers-by: Jesus Christ is Lord.

On the stage of this same theatre, on 6 June 1966, a fervent Lisbon cheered the end of the tour that brought the adaptation of the northeastern Brazilian Christmas play Morte e Vida Severina by the Brazilian poet João Cabral de Melo Neto to the city. Brought by TUCA (the theatre company of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo), João came along and was so happy with the enthusiasm of the audience at the premiere that he followed the group to further performances in Coimbra and Porto. This and more was shared with me by Rafaela Cardeal, a researcher from Rio de Janeiro who dedicated herself to a research project that culminated in her doctoral thesis on the Portuguese reception of the poet’s work.

According to Rafaela, the play’s success is due to many factors. But among them is the way in which its characters, dressed in white and without scenery, represented a social critique of the reality of the Brazilian sertão that echoed Portuguese life under the dictatorship. Young audiences, who were fighting against fascist repression, identified with the message of the play, which was set to music by Chico Buarque at the start of his career. At the time, the denunciation of social inequality and oppression became a symbol of resistance against Portuguese repression.

We were sitting at a table in Pão de Açúcar – a 1950s café opposite the Império, or rather the Universal Church, as it is now known. At the back of the café there is a tiled panel showing the irreverent landscape of a Rio postcard, which for a significant portion of my life was part of my daily commute to university. The choice of location was not intentional. But Pão de Açúcar and a cinema-turned-Universal Church couldn’t have made me feel more at home.

My move to Lisbon calcified within me an identity that, although it had never gone unnoticed in my life, became extremely visceral; Brazilianness. It seems that when I crossed the Atlantic, I symbolically found myself facing a process of death and life. I believe that every immigrant experiences a rebirth. And this whole process is painful in many ways. Life here has taught me to perceive violence differently from what I was used to. Violence here is not explicit, it is subtle and institutional. On many occasions, violence is dressed up as bureaucracy.

At first I thought I knew why I had come here, but a few months later I’m no longer sure. I know I fled Rio’s violence and I know I came in search of a better quality of life, but I’m no longer very clear about what that means. Just as Severino realized, perhaps the discovery lies in the journey and not in the destination. My encounters along the way have helped me to understand the meaning of being Brazilian and of my path.

It was the first week of summer when Sidnei arrived in Lisbon last year. Alongside a suitcase and a small rucksack, he carried with him the promise of a better life. His life on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, far removed from the fabulous imagery eternalised in the bossa nova of Tom Jobim and Vinícius de Moraes, brought trauma. The successive muggings and gratuitous violence that accompanied the simple reality of existing made him decide to build the rest of his life in Portugal.

With absolutely no guarantees, he crossed immigration control with a three-month tourist visa. It’s been nine months now and under no circumstances is he considering returning to Brazil. And that doesn’t necessarily mean that he has found paradise. On the contrary, here in Portugal he has discovered new challenges in his existence as a working–class person. He obviously has a better quality of life but with a new sense of vulnerability. Unable to settle his immigrant status, he feels in a kind of limbo. Unsure of when he will be able to cross Portuguese borders and explore Europe as he dreams of, he lives day-to-day, working in a restaurant in Porto, close to the trendy Bolhão Market.

‘Slavery’ – that is the word he uses to describe his day-to-day life. This became clear when he tried to look for a training course that enabled him to find new job opportunities and couldn’t find one that fitted in with the reality of a person who starts work at 12 noon and has no time to leave. It all depends on the customers. It may be that the restaurant you work in finishes at 11pm, or maybe midnight. You never know when a group of hungry tourists will arrive.

Behind the counter, at off-peak times, you watch life happening outside. He feels like he’s in an aquarium, watching people pass through the glass that separates him from the life he longs for. On the few sunny days in Porto’s winter, the feeling of suffocation consumes him the most. That’s when he most wants to feel the warmth of freedom.

During my first month in Lisbon, I lived in a hostel in Chiado. One evening in October, I found Laís in the kitchen chatting to her girlfriend on a video call. She was excitedly sharing the videos she had recorded at the concert of Brazilian singer Jorge Vercillo. I would have gone too if I’d known; I had learnt to like his songs as a result of my mother’s influence. At the beginning of the 2000s, it was what I listened to on a daily basis.

I identified with Laís because she was only there for one night, returning the following day to Setúbal where she lives because of her job as a chef in a restaurant. Thinking back to that moment, I realise the irony of us meeting in a kitchen. Since then, our friendship has gone from strength to strength and with each meeting I learn more about her story.

Our meetings are rare. Like me, Laís works full–time shifts split into two with an extended break in the day. Three–hour breaks do not often permit get-togethers with friends who live 50 kilometres away. But one Sunday at the beginning of February, she managed to get half a day off and came to see Virginia at the theatre, a play written and starring Brazilian actress Cláudia Abreu. At that screening, I saw Brazilian singer Fafá de Belém in the audience honouring her friend. Belém is from Pará in the north of Brazil, the land of my grandmother.

Laís was born in the same region. To be more precise, she was born in the municipality of Macapá in Amapá. But when she was very young, she moved to Natal, the capital of Rio Grande do Norte, which was where she grew up. During her childhood she took part in chess championships, and she was good, as she is keen to point out. She won state, municipal and even regional championships. She never won a national championship, but she did finish in the top 10.

This experience of travelling for championships at a very young age boosted the free spirit she has today. So it wasn’t too difficult to take the decision to move to Punta Cana for work, where she led a kitchen despite not speaking Spanish at first. Being an immigrant, therefore, is nothing new, but she knows that each move throws up new challenges. The ease with which she can move around has led her to yet another destination, this time to Albufeira in southern Portugal. As well as looking for a job that respects her as a human being, proximity to the beach is a necessity in her life, as it is for many of those who grew up on Brazil’s coast.

When we left the theatre and went to dinner, I noticed, as she took off her coat, a huge burn on her left forearm. These are recurring marks left on the bodies of the kitchen workers. When she told me about the accident, she conveyed a sense of normality and a way of looking at the recurrence of this as part of the job. However, I perceive a strong symbolism in the marks that this work leaves on the bodies of a significant majority of immigrants.

In parallel, I think back to that stage at the Maria Matos Theatre, with a performance of Virginia Woolf facing the dilemma of becoming a great writer. On the edge of sensibility and madness, I observed the creative process of this woman who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, faced homeric difficulties in proving her excellence in a literary milieu of men. For Woolf, pain played a fundamental role in her work. But I wonder if it really needs to hurt. From that day on, many reflections surround my mind and a phrase within the long monologue still resonates with me: ‘freedom is having time to live’. And so I realise that I, Laís and Sidnei are not truly free.

Like us, Davi isn’t fully free either. I share the vast bulk of my six-day working week with him in the same restaurant. I’m a waiter and he’s a kitchen assistant. Occasionally I go into the kitchen to help him with whatever is needed, and there I discover an added dimension to catering; it doesn’t matter if the restaurant has customers or not, there’s always work in the kitchen.

If they’re not dealing with the immediate demands of the customer, they’re preparing for the next day. Whether it’s making pudim, my favourite dessert, which tastes like childhood to me, or preparing the cozido à portuguesa – Portuguese stew – to be served for lunch the next day, the kitchen is always looking to the future.

One Friday, Davi and I decided to break the humdrum of our routine and went to the bohemian Bairro Alto. During our walk from Rua de Santa Marta to our final destination, we spoke about life along Avenida da Liberdade. It was on this journey that I realized that when he decided to leave Curitiba, in the south of Brazil, he wanted to explore the world. Where he came from, he had a stable job as an administrative assistant at a large company, he lived in his own house and life seemed complete. Yet something was missing.

So he decided to come to Portugal. His family doubted him, but he came here anyway. And in the heat of excitement, a few months before his departure, he bought a ticket for the day of his mum’s birthday. On the morning of 20 May 2024, he went to her house to have coffee and say goodbye. She didn’t want to eat, they said goodbye and he left for the airport with no regrets, he was truly happy. At the time, mother and son hadn’t realised what that moment meant. One day she rang to say that it had finally sunk in and she realized that he had left.

At Bar da Vera, a place that brings Brazilians together in Lisbon’s nightlife, we discovered that the one beer that we had agreed to have turned into two bottles of wine and some shots with peculiar names. Davi has an inexplicable energy for someone almost 30 years old. No matter how hard he works or how tiring the day has been, he always wants to have fun. The DJ was playing Brazilian music and it wasn’t long before we gave up on going back early. We had fun, met people and lived a different life. It’s always satisfying to meet people with whom I share something, it’s a mental exercise to keep my place in mind. That night, being an immigrant seemed like a mere detail.

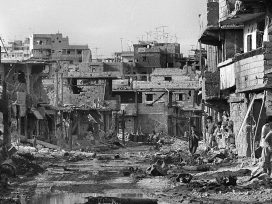

Seventy years have passed since Severino’s journey hit the bookshops of Brazil. As well as a social portrait of the country, this character is the archetype of the modern individual who, faced with the progress of his time, has been swallowed up by the premise of modernization. Poverty and hunger are still a reality in Brazil, there’s no denying that. Just like in so many other places, hundreds of immigrants are braving the sea. Adrift in the immensity of the ocean, severe deaths are witnessed across Europe. According to a report released by Caminando Fronteras, more than 10,000 migrants died trying to reach Spain in 2024. It would be reckless to try to compare the drama of these journeys to our own. But we also can’t deny that new times have brought other dilemmas and anxieties to the Brazilian dimension.

‘We don’t just want food. We want food, fun and art. We don’t just want food, we want to go anywhere.’ In these verses written at the end of the 1980s, Arnaldo Antunes from the Brazilian band Titãs signalled a new set of demands. In 2025, at a time of late modernity, I use Stuart Hall’s arguments about identity to explain the process of fragmentation, instability and constant reinvention to which we are subjected.

Globalization, migration and the collapse of fixed references destroy the idea of a continuous and coherent ‘I’ – like Severino. In Lisbon, we experience a reality that imposes itself on our Brazilian existence. My identity, previously anchored in Brazil, is rebuilt in transit between languages, customs and bureaucracies that place me in a nether zone – neither here nor there.

This text is part of the Come Together Fellowship Programme, a training programme for young journalists led by cultural journal Kurziv. This article was originally published in Portuguese by the cultural media platform Gerador.

Published 3 September 2025

Original in Portuguese

First published by Gerador (Portuguese version); Eurozine and other Come Together consortium partners (English version); published online 12 June 2025; in headline 3 Sept 2025

Contributed by Gerador © Dan Alves / Gerador / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

What happens to democracy when governments court the rich and highly skilled, offering citizenship as privilege, when those in need are turned away? This year’s Speech to Europe takes the concept of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ migrants to task.

The outbreak of the Lebanese civil war fifty years ago inaugurated an era of nation-state collapse in the Arab world. In failing to mediate, the international community carries responsibility for the sense of impotence felt in societies in which violence dominated everything.