These days, it seems that a detailed inquiry into what philosophers ‘do’ is part of the register of philosophizing itself. Those working in the fields of the natural sciences and technology, generally speaking, do not engage in the same kind of reflection on their activity; they consider it unnecessary, as do those in the social sciences and humanities, though to a lesser extent. Through this line of questioning we most often also expect a clarification of what philosophy ‘is’. To find out what they do, philosophers try to define the discipline. This challenge is posed repeatedly for everyone who begins to study philosophy as well as those who do not. When we think about philosophy’s social status in and general usefulness, we cannot ignore the initial dilemma of its essence and definition.

Shortly before her tragically premature death in 1995, philosopher Gillian Rose wrote:

To be a philosopher you need only three things. First, infinite intellectual eros: endless curiosity about everything. Second, the ability to pay attention: to be rapt by what is in front of you without seizing it yourself, the care of concentration – in the way you might look closely, without touching, at the green lacewing fly, overwintering silently on the kitchen wall. Third, acceptance of pathlessness (aporia): that there may be no solutions to questions, only the clarification of their statement. Eros, attention, acceptance.

Of course, philosophy is more than just the sum of these parts, from which no solutions are to be found. We cannot reduce it to a mere psychological description of why someone would spend their life striving for wisdom. Endless speculation about what exactly philosophy does may perhaps indicate a desire for self-contemplation. A slightly more critical approach shows, however, that until now it has not sufficiently reflected on its own activity, and evading definition may perhaps be part of its destiny.

It could be even worse. The doubt could be justified. Some anti-philosophy skeptics would say that a large part of philosophy does not even deserve that name because it does not try to meet philosophy’s most basic requirements: internal coherence and a clear methodology. This would be truly urgent if we wish to avoid the greatest danger, the tendency to identify any sort of ‘philosophizing’ with philosophy. In this way philosophy may also contribute to what we might call it’s own ‘fateful self-rejection’, succumbing to its own prejudices, repudiation by the public, and attempts to isolate it as a discursive form. Even when it successfully avoids such criticisms, another danger looms: philosophy remains how it has always been or becomes ‘armchair philosophy’.

Professional philosophers want to find answers to often abstract, general questions that are nonetheless important for making sense of the structure of the world, society, and humanity. Based on their findings, they formulate elaborate, systematized theories. Sometimes, however, they go no further. The next step would be to weed out weak answers and develop more convincing ones, cite specific examples of the question examined, and subject them to verification and a search for counterexamples. They often fail to do this.

Many claims and theories achieve undeserved recognition and promotion without having been verified. Of course, in many instances, it is impossible to do this using the scientific method, or even in principle. Some theories become successful because of external factors, or even due to their contradictory nature and absurdity.

As a result, philosophy faces two difficulties from those inside and outside its rigid institutionalized form. Its internal institutional difficulty is, undoubtedly, its hasty self-complacency. Traditional methods of philosophy, as Timothy Williamson argues, encompass reflection, but no interaction with the world in the form of measurement, observation, and experimentation. Philosophy quickly becomes an armchair occupation as a result. Even in this regard, however, there is no consensus. Many philosophers disagree with this approach, dismissing it as too restrictively analytical to understand the essence of philosophy.

Many believe in a less ambitious mission for philosophy. For them, its task is not to develop theories but to shine light on evidence, ambiguity, and errors, and subject them to a process of verification or clarification. For others, none of the above holds true. In this case, philosophy is not, as Slavoj Žižek says, about finding answers, but posing good questions, and only this. These dilemmas already apply to academic philosophy, but things are even more chaotic outside the academy.

Is it too rigorous to say that the field of philosophy is shaped only by what professional philosophers do? Nowadays, as a respected field of study, it has systematized its knowledge and its existence, and for a long time it has not been reserved just for the amateur activity and random curiosity of the individual alluded to by Rose. After thousands of years it has become a treasure trove of knowledge; it is taught at the best universities around the world, has become part of the curriculum in primary and secondary schools, and there are thousands of research institutes. It has shaped an important part of our knowledge and understanding of the world and of society, had a lasting influence on developments in the humanities and social sciences, and played an important role in political and social processes.

It has taken up a certain, albeit perhaps marginal, space in society and the public, universities, and non-academic pursuits. This is where the serious issues come from. In philosophy, more than any other discipline, it is unclear if its life is necessarily tied only to the academy. We can even wonder if there is something in its nature that inevitably compels it from this kind of position and evades institutionalization.

More than a century ago John Dewey published the essay The Need for a Recovery of Philosophy. Here, he critically examines the role of philosophy at the beginning of the 20th century in American life. He expresses deep concern about the anachronistic and cumbersome nature of philosophy, driven away from mainstream trends in modern life. Dewey is indignant about how philosophy has become merely the domain of narrowly specialized experts who spend too much time debating purely for the sake of debate rather than devoting themselves to topics offered by ‘modern life’.

How familiar these remarks seem even today! In Socrates Tenured: The Institutions of 21st-Century Philosophy, Bob Frodeman and Adam Briggle argue that professional philosophy has distanced itself from its true roots. Socrates, they argue, would never end up in a philosophy department even if he wanted to. Not only would he resist the organization of secondary literature, the search for citations, and reviews of arguments that would meet the criteria of reviewers for academic journals; as someone who had spent his life having conversations with fellow citizens at the Agora of Athens, he would likely protest against what is done in the name of philosophy today.

Frodeman and Briggle diagnose the pathology of contemporary philosophy and ask if academic philosophers are even prepared to assist society through their reflections. They put forward a provocative thesis: philosophy, they say, must avoid its own incarceration in philosophy departments to become ‘field philosophy’.

This idea has been taken as a point of departure for this issue of Dialogi. That is to say, to debate the question of what philosophy does and how it does it. We aim to confront its position in the public sphere, status in modern society (both within and outside academia), and in the specific case of Slovenia. Questions include: How successful is it as a public activity? How does it resist the demands for ‘non-thinking’? How does it think about the conditions for its own activity?

Neoliberal finance capitalism, the ideology of consumption, and a prevailing nihilism have also altered philosophy’s former role. Has the perception of philosophy in the social, educational, or economic sphere changed? Has its position been further marginalized? How is philosophy as a discipline and how are those who belong to it institutionally responding to the challenges of the time? Does it remain closed off in its complacent ivory tower? How is it reflected in action and how does it reflect the events around it? Has the space of its institutional life opened or closed? How do philosophers take on the status of public intellectuals and thinkers of social change when its place in the education system is threatened or removed entirely? What is it that makes it still indispensable today, when questions of its usefulness lie in its ancient foundations and it has had to constantly defend itself against criticisms of irrelevance? And finally, should it leave academic institutions, and if so, why does it not do this?

The problems are numerous. For some, philosophy is itself at fault. For others, it is not. For the most part, both are true. Humanities funding is being cut back the world over, and regular employment in the field and public funding is becoming increasingly restrictive. Government funding increasingly demands that research is required to have directly measurable effects and a tangible economic impact.

Although our increasingly globalized culture, with all its technological breakthroughs and scientific advancements, raises ethical, existential, and political dilemmas that philosophers should address, the crisis has swept through philosophy.

On the one hand, philosophy finds itself in a precarious place in the neoliberal university, reflected in an increasingly hostile attitude towards its standard models. In a society that demands that we prove our usefulness according to measurable effects, philosophy as an end in itself is increasingly seen as a nuisance.

Recently, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Maribor, writing in Večer, openly stated ‘We are redirecting philosophers to medicine and computer science.’ She was referring to the irrelevance of some courses of study and the unemployability of certain professions.

Ironically, Frodeman and Briggle advance a similar idea from a completely different perspective. They ask why philosophers dwell on difficult ‘insider’ topics like metaphysics, when they can come across the same problems just by reading the newspaper? They provide the example of a Washington Post article about a patient taking heart medication with a hidden chip. The chip is linked to a computer by which the patient and their doctor can see if they took their medication. The story then describes nanosensors, which will soon be on the market: they will swim in the bloodstream and detect signs of a heart attack before it occurs. These are questions that fall under the heading ‘Existence and Identity’ in the Oxford Handbook of Philosophy.

Frodeman and Briggle conclude that this is not really just about new medical instruments, but serious metaphysical questions about the nature of the ‘self’, the boundary between ‘organism’ and ‘machine’, and similar problems. In the 1980s, so-called ‘applied philosophy’ led, they note, to an interest in environmental ethics and bioethics.

The ‘field philosophy’ they propose would, in their view, allow philosophy to escape from university departments and shift between university and non-academic fields. It could then come in contact with nongovernmental organizations, laboratories, communities, companies, and political decision-makers.

Philosophers could, they argue, be part of other departments, like medicine, law, or science. Their transition would be reflected through collaborations with specialists from these fields. In this way, philosophy could shake off some criticisms.

We can imagine, however, that some philosophical traditions would protest strongly against the fusion of philosophy with science. They might think this indicated philosophy’s loss of autonomy. They might simply think it is inappropriate, given the nature of philosophy. At the same time, philosophy often fails to deal with the major issues of our time. If it loses whatever place it currently has in society, philosophers themselves will be to blame.

More than fifty years ago, Chomsky wrote that strengthening the integrity of intellectual life and cultural values is the most urgent and crucial task of universities and academic disciplines. He expected philosophers to take a leading role in this. If they do not, he said, they are abdicating their responsibility. We must, then, ask, do philosophers have such obligations? And why is it theirs and not someone else’s?

Professional philosophers usually direct their academic activities to research and teaching – exactly what would irritate Socrates. Chomsky’s problem is wider, though, since we have obligations towards national and global politics regardless of the those assigned to us as citizens. These specific obligations arise from the particular skills that set philosophers apart from for example, biologists or mathematicians. Why? Because they are in a relatively advantageous position. No other profession offers better tools for the analysis of ideologies and a critique of social knowledge. Philosophical analysis is, ultimately, the key to understanding the current global social and cultural crisis.

These responsibilities should be greater today than ever before. How have philosophers responded? Very badly. Philosophy has not even met the minimal obligation that it should think about its own relation to the public when people ask what use it is.

Does philosophy need another ‘Socratic moment’ today? Should it return to the Socratic ideals of the philosopher embedded in public affairs and politics, adapted to modern needs? Not necessarily. Things are not so simple. It is absolutely right to say that one of philosophy’s essential features is practical involvement in public affairs is one of philosophy’s essential features. This engagement, as the example of Socrates shows, precedes its institutional transformation. This is not entirely unproblematic, though. Perhaps, in fact, it is not entirely accurate to say that modern philosophy, in its present institutional form, has abandoned the public interest function altogether.

Ultimately, the problem already lies in the idealization of the historical Socrates. Even the thesis that he wanted to deal with public affairs may not hold true. Socrates deliberately avoided politics, since he considered that unjust rulers would not tolerate a gadfly of his type. Conversation with fellow citizens in the agora does not have much to do with intervening in the direct political fabric of the city. At the same time, however, he did not reject such discussions outright.

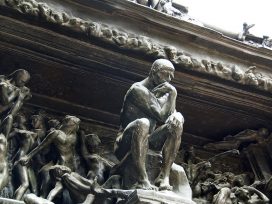

Photo by Jon Himoff on Flickr

Rodin’s Gates of Hell at Musée Rodin in Paris.

In any event, Socrates in the agora is the very antithesis of the armchair philosopher. However, philosophers’ greater public involvement alone would not necessarily be sufficient for our needs. It is not clear how they could contribute to a change in an increasingly deintellectualized social and media climate, in which the status of the public intellectual has long since been eroded and marginalized. It is increasingly difficult to penetrate the mass media and public space. Journalists and editors try to attract a large readership in the ‘attention economy’ during a time of general ‘tabloidization’ and superficial thinking. Attention is earned primarily by ambitious provocateurs, lawyers, or IT specialists who provide of disposable ‘instant truths’. Put another way, philosophers do not have only themselves to blame for not taking on the role of public intellectuals.

In Slovenia, too, we are extremely reluctant to devote ourselves to the reality that surrounds us and we run away from it. Perhaps, for lovers of wisdom, and especially for philosophers, social reality has never before thrown up so many direct challenges as today. Whether they are prepared for them and react in the ways that are expected of them and whether they have reasoned well enough about the state and situation in which they find themselves will be shown not only by time but also by their fate in the years to come.