Almantas Samalavicius: 1990 was a year of hope and expectation all over east and central Europe. Developments since then have brought different sentiments. Though the main goal – freedom – was attained, it came at a substantial cost: the loss of unity, social solidarity and, more recently, growing income disparities, brain drain and economic emigration. All these tendencies reflect realities that are more complicated than people of the region ever imagined in those emotional years of revolutionary upheaval. What, in your opinion, were the most important sociopolitical gains in eastern Europe and what can be interpreted as losses?

Daniel Chirot: The changes that have occurred in this region since 1989 represent, on the whole, one of the most successful examples of revolutionary transformation in history. While the American Revolution, which resulted in the formation of the United States in the late eighteenth century, can be counted as a success, the French Revolution of 1789 brought terror, military dictatorship, and a series of terrible wars that only ended in 1815, leaving France ruined. Most of the later revolutions, including those of 1848, ended by strengthening autocracy. The Bolshevik Revolution, as we all know, was a human and ultimately an economic disaster.

Mussolini’s and Hitler’s attempts to transform their societies in a fascist revolutionary way were monstrous failures. Mao’s Chinese Communist success in 1949 was the prelude to millions of murders, and then the largest famine in human history caused by Mao’s Great Leap Forward in 1958-1960. The estimate is that 45 million died. Cambodia, North Korea, Cuba and others had their revolutions that also brought death and slavery to millions, and have left ruined economies in their wake. In eastern central Europe, the revolutions that overthrew a bankrupt social system resulted in only one catastrophic war, in Yugoslavia. Elsewhere, they were largely peaceful. Even in Romania deaths were limited. Since 1990 there has been economic growth, much greater freedom and the establishment of real democracies. Of course there is inequality, but there was before, just that it was better hidden.

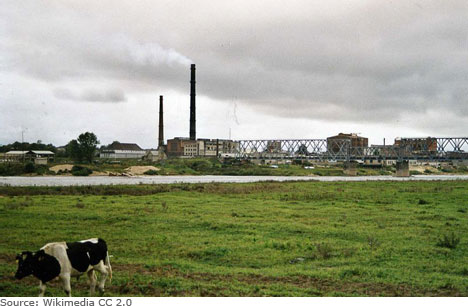

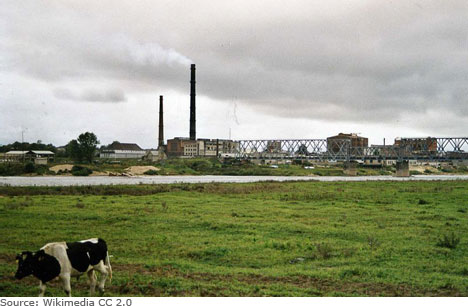

Naturally the utopian dreams of many have not been satisfied, but where is there utopia? When those holding utopian ideologies come to power, they bring only disaster. Let us not forget that communism left in its wake ruined economies, outdated infrastructures, societies where trust had been destroyed, institutions that did not function, and pervasive cynicism and corruption. To me it is amazing that in most countries of eastern central Europe things have turned out relatively well. That is not the case in some former Soviet Republics where, unfortunately, old institutions, corruption, and undemocratic practices persist. In that sense, the Baltic Republics are clearly the most successful former parts of the former Soviet Union. Think of Belarus, or Armenia, or the Central Asian Republics to see how much better off are the three Baltic countries.

AS: Much of the present social disillusionment in eastern central Europe, and Lithuania in particular, has been caused by the large-scale privatization policies introduced immediately after 1990, which were only partially successful and, in many cases, socially unjust. As we know, privatization was strongly backed by the western powers and international organizations such as the IMF and World Bank. Indeed, the first two decades of post-communism coincided with the world-wide reign of neoliberalism both in international politics and the economy, even though there had been cautious voices against total privatization (such as John Kenneth Galbraith or communitarian thinker Amitai Etzioni). These days, when neoliberalism seems to be losing its ground, can any lessons be extracted for eastern Europe?

DC: I agree that the prescriptions of the so-called “Washington Consensus” of the 1990s, in other words the rigid application of neoliberal free market economic policies, have turned out to be foolish. They brought the Great Recession of 2008 that still persists, and adherence to such ideas is probably responsible for much of the misery in southern Europe. It isn’t that capitalism can be said not to work, but that free markets cannot by themselves function or hope to support a reasonably fair society without government support. Karl Marx may have been wrong about many things, but he understood the contradictions of capitalism and its propensity to create huge inequalities and periodic crises. What made his predictions fail is that the leading capitalist societies eventually adopted institutions to mitigate these problems. Too many experts, particularly Americans, gave poor advice in the 1990s, not only to eastern central Europe, but to other countries as well, including their own, the United States. We are paying for this now. On the other hand, eastern central Europe is still better off than it was before 1989, even though some sectors of the population are doing poorly. Considering how much of a disaster late communist economies really were, reforms could have turned out to be much worse. I hope that the failure of neoliberalism teaches everyone the right lesson. Capitalism works, but not its most unregulated form. We would do well to go back to the ideas of John Maynard Keynes and abandon once and for all the “Chicago School” economics of Milton Friedman and his even more extreme followers.

AS: You have argued that economic backwardness in eastern Europe has its own peculiar historical roots. Could you summarize these? What are the prospects of eastern Europe overcoming its eternal fate of being “semi-peripheral” to the modern world? More generally, do you subscribe to the world systems theorists’ classification of the world into categories of centre, periphery and semi-periphery and forecast different degrees of economic success for these regions?

DC: No, these categories only made sense in the past when a few western powers dominated the world economy and controlled vast empires. The question as to why the region was behind western Europe is the wrong one. Instead, we need to ask what made a small part of the West different. Once the West began to grow economically and to industrialize, the parts of eastern Europe that interacted most with the advanced parts of Europe did not go backward. They became, instead, the most advanced parts of eastern Europe. So the whole theory of peripheralization is wrong. Even today, it is Poland, the Baltic countries, the Czech and Slovak Republics, Hungary and Slovenia that are better off than the Balkans, which were shielded for a longer time from western trade and influence. I understand that intellectuals in eastern and central Europe love feeling sorry for themselves, but on a world scale, these societies are not doing so badly. There is no question that they were more backward in the nineteenth century, and that the twentieth century treated them badly; but World War I, World War II and decades of communist rule have caused more harm than any kind of peripheral or semi-peripheral status. I can understand why Marxists hold on to this notion that it is participation in the world economy that has caused backwardness, but the evidence simply doesn’t point to that except for some obviously politically exploited colonial areas in the past.

AS: During the 1990s, eastern and central Europe was often referred to as the “post-communist” realm. However, as soon as the larger part of its countries joined the EU, the discourse of and on post-communism was gradually abandoned in favour of seemingly more “promising” interpretations. This turn was generally greeted by local politicians and academics. Yet some critics are inclined to think that this discourse was abandoned somewhat too early, and that some opportunities for analysing eastern European societies were therefore lost. What do you think of the change in this frame of reference?

DC: It has now been more than twenty years since the collapse of European communism. I agree with those who think that it’s time to stop thinking in terms of post-communism for those countries that are now part of the European Union. If, however, we look at Belarus, at Russia, at Ukraine, and at most of Central Asia, that is not the case. In most of these countries the same people are running things – sometimes the old Communist Party bosses as in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, or the former KGB in Russia. The socialism part of communism is gone, but the corruption, autocracy and inept state control of key parts of the economy remain. Though there was some danger that this would happen in eastern Europe, for the most part it has not. Especially if we look at the northern part of the region, the transition away from communism has been made.

AS: In some of your publications you seem to argue against attempts to stress the differences between so-called central and eastern Europe on the one hand and western Europe on the other (you have referred to Milan Kundera’s revived concept of Central Europe as somewhat propagandistic). Should one interpret developments in Europe (especially its eastern or central part) only from the point of view of “modernization”? Aren’t there different “modernizations” as well as “globalizations”?

DC: Of course there are different cultural traditions. Even in western Europe, France, Italy and Germany remain different in many ways. To take an extreme example, it is difficult to imagine that the Germans would freely continue to elect as their leader a thoroughly corrupt clown like Berlusconi for so long. And there is no question that the past continues to influence the present. If one goes to East Asia, for example to South Korea, Japan or parts of China, it is obvious that modernization is not identical to what the West experienced. Even England and the United States feel like quite different places. That is not the point. Modernization means a rising standard of living, a huge demographic shift from high death and birth rates to low death and birth rates, urbanization, high literacy, smaller families and so on. That has been happening everywhere, even in the poorest pars of the world. Eastern Europe is obviously not as rich as western Europe, but it is far from being one of the poorest or least modernized parts of the globe! In fact, communist regimes were themselves modernizers, though they did it in an inefficient and autocratic way that ended up, after the first great periods of progress, in slowing down further modernization.

A Lithuanian going to Shanghai will easily see that old cultural patterns continue to shape the present; on the other hand, he or she will immediately understand much that is going on. There will be ATMs; in the big hotels and major businesses English is useful; taxis and public transportation will be easily understood; and even if this Lithuanian speaks no Chinese, he or she will be able to recognize what is going on in a lot of the television programs. When I lived in rural parts of Niger in the 1960s, in places that were truly not modernized, I often thought I was living in a different era. There were nobles and slaves, courts of local emirs that were right out of picture books of the Middle Ages – peasants who had absolutely no idea that there could be whites who weren’t French (it had been a French colony), and whose belief in magic spells and witchcraft was so solidly entrenched that even their superficial Islam had not made much of an impression. This is what convinced me that there is such a thing as modernization, and it does have strong similarities all over the world, mostly for the better. It is nice to talk about how much we have lost because of modernization, but seeing children dying of measles or in agony from easily curable appendicitis made me reject all the anti-modernization nonsense that some nostalgic intellectuals put forward.

AS: The famous “clash of civilization”, the concept coined and promoted by Samuel Huntington with all its inherent problems, has turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Developments after 9/11 and the rise of Islamist fundamentalism have brought new fears about the future in Europe as well. Some have urged that we speak instead about the “clash of globalizations”. However that may be, the presence of Islam in Europe remains strong. Does this presence give ground to speculate about possible “civilizational” conflicts?

DC: Huntington was a brilliant political scientist who let his prejudices get the better of him as he grew older. His last big book was an attack on immigrants from Latin America who could never, he claimed, be integrated into American life – something about which he was entirely wrong. Let’s look more closely at the “clash” before we get carried away. In late 1940 there was a huge “clash” of civilizations in Europe between fascism and democracy. Each promised a very different future. Stalinism also offered a very distinct kind of society. Hitlerism, Stalinism, and the remaining democracies, chiefly the United Kingdom and, when it joined the war, the United States, were all “modern”. But one could hardly imagine more different ways of organizing social, cultural and political life. All were European, and even by Huntington’s standards Nazi Germany and England were part of the same civilization. So the clash within European civilization was extremely severe.

Now, it is quite true that the failure of what can be called “Third Worldism” or socialist nationalism – as practiced by the likes of Nasser, the Ba’athist Party, the Algerian post-independence regime, Sukarno, or their many lesser imitators, including Gadaffi in Libya – were all abject failures. They did not modernize their societies very well at all. Nor did the more supposedly conservative leaders such as the Shah of Iran or the Pakistani military rulers. Reactionary Salafists have gained popularity and sparked a wave of religious fanaticism because the faults of the previous regimes are seen as a failure of westernization. But where such a religious ideology has gained power, such as in Iran, the result has been a disaster too. So we can be sure that, as more Islamist regimes come to power, unless they follow a moderate and democratic path, as in Turkey, they will also fail and discredit themselves. So the real clash is not between different cultural areas, but within each one. We can see this today in Iran and much of the rest of the Muslim world.

Even in the United States the real clash of civilizations is between the rightwing evangelicals and some parts (but only some parts) of the Catholic Church on the one hand and the more tolerant and secular parts of the population on the other. Listening to someone like Rick Santorum, I thought of him as an American Taliban – harshly intolerant, wanting to put women back into traditional roles, opposed to contraception, rejecting the basis of modern biology and science, and bitterly hostile to the outside world. He did not gain the Republican nomination for president, but he is influential. So what are we to make of this kind of cultural clash? It is within and not between civilizations.

I recognize that in Europe there is a problem with poorly integrated immigrants, many of whom are Muslim, but the idea that somehow they will take over Europe, or be forever unassimilated, is as foolish as assuming that because the Catholic Church resisted modernization for a long time Catholics and Protestants would never be able to live in peace. Except in Northern Ireland, they do.

AS: Recently there has been a revival of leftist ideologies and discourses all over eastern Europe. Younger intellectuals have set out to reanimate the “Left” with a set of western discursive practices (multicultural, feminist, queer critique and the like). Do you think such “revivalism” has any potential?

DC: The “end of ideology” proposed by Daniel Bell a half century ago was exaggerated even then. In fact, not long after that book, which was based heavily on the death of the old Left as a dynamic ideology, a new kind of Left surged, and by 1968, it was very clear that ideology was far from ended. I once asked Bell if he had abandoned the idea of the end of ideology. His answer, which was no answer at all, was that this was like asking him when he had stopped beating his wife. In other words, whether or not he did (and there is no evidence he did!), once the question was posed that way, he could not answer without seeming foolish. Later, with the fall of European communism, Fukuyama and others made the same claim. But ideology never ends. Yes, of course, there will be a resurgent Left, though it is more likely to take the form of protest against the unfairness of the existing economic order. We see this slowly forming in the United States. A large part of the population wants a fairer taxation system, greater toleration of gays and racial minorities, and greater investments in education. But there is also a very active Right that does not want these things. What are called the “culture wars” in the United States is actually another form of a quite traditional left-right struggle. In Europe, both the Right (think Viktor Orban or the anti-immigrant parties in places like the Netherlands or Denmark) and the Left, particularly in southern Europe, are going to get much stronger. Economic crises have a way of doing that, and the one we have now is not going to go away so quickly.

AS: Recent years have been full of controversies all over eastern and central Europe. Most recently, Hungary has criticized the EU’s multiculturalist policies. What are the roots of this social and, perhaps, cultural discontent and what are the possible remedies for present and future ruptures in the region? Are these differences in attitudes a threat to future of common Europe?

DC: These debates are the sign of an active struggle between left and right, between a more inclusive visions of what society should be like and a more restricted, inward looking one. This is not in itself a threat to European unity. What is a threat is that Europe’s institutions are not strong enough. The European Parliament does not have enough power. There are inadequate monetary and financial institutions. The euro crisis is much more dangerous than multiculturalism. I cannot predict what will ultimately happen, but again, looking at the past, let us not forget that what almost brought Europe to ruin in the first half of the twentieth century was not so much an original cultural clash, but the stupidity of its ruling elites. This led to World War I, to the utterly wrong economic policies that made the Great Depression so bad, and to the ideological extremism that emerged from those catastrophes. Will something like this be repeated? Very probably not, so I am not as pessimistic as some people are.