Home-making

At times a safe-haven, at others prison-like: when COVID-19 lockdowns restricted entire lives to the home all around the globe, perceptions of everyday space changed. But do our relationships with enclosed living, especially during quarantine, reflect pre-existing meanings of intimacy ascribed by psychologists and artists to the home?

The home as concept

Phenomenological discussions of home delve into how it relates to our inner world and its location. Addressing the subject in terms of concepts of house and dwelling requires an understanding of the home as a constructed object in relationship to its environment.

In such discussions, ‘being at home’ or ‘feeling at home’ come forth as key phrases that help us understand the concept of home. Home is where you’re born and where you develop. The meaning of home can only be constructed through the experience of that specific place.

As Norberg-Schulz writes, home is the act of placing yourself between the ground, the sky and the horizon, experiencing the cycle of days, nights and seasonal changes in that location. It is where you belong, perceive your position on the earth and look out at the world. The question of ‘how’ defines corporeal forms and ‘where’ describes spatial relationships. It is only through a sense of place that one can feel at home in the mountains or on a beach.

However, to be able to dwell in that place, one still needs a physical shelter.1 According to Norberg-Schulz, the word ‘dwelling’ means something more than having a roof over our head and a certain number of square meters at our disposal. First, it means to meet others for the exchange of objects, ideas and feelings – to experience life as a multitude of possibilities. Second, it means to come to an agreement with others – to accept a set of common values. Finally, it means to be oneself within a small chosen world of our own.2

In Bachelard’s writings, the ‘dwelling’ or the ‘house’ is the place, the location and the world of lyrical narrative, the poetic imagination. He sees the house as a metaphoric device to comprehend the human soul and the idea of home. The house is the secret and enclosed space in which we shelter, daydream, live, isolate what’s private for us in drawers and wardrobes. In other words, it is an enclosed space where our intimate and private values are captured within a single fundamental context.3 If we look at it intimately, even the humblest dwelling has beauty.4

The house is the point from which we look out at the world, and it is also our personal universe. Therefore, the meaning of inhabited space transcends geometrical space. The house helps one inhabit the world despite the world outside.5 This is a state of rivalry fuelled by the positive and negative contradictions between the house and the universe. While the universe is cold, the house is warm. It is because the outside is cold that the house is warm.6

A womblike space

Elen Winata, Anonymous, Singapore, 2020/2021 (Artists share artworks made during the pandemic – CNN Style). © agreement with Varlik

Freud claims that our mother’s womb is the first home that we experience, and it symbolizes our subconscious perception of home. According to his analysis, dreams whose content follows subjects such as passing through narrow spaces or being in water are based upon phantasies of intra-uterine life, of existence in the womb and of the act of birth.7 In psychoanalytical discourse, the mother’s womb is our first experience of an enclosed space that is familiar and safe. Oliver Marc in Psychology of the House points to the mother’s womb as the origination of our idea of building houses.8 Only such a primal instinct, he suggests, could justify the intensity of this desire.

The womb is a shell providing natural protection. It is not a place that is abandoned but one departed from by necessity: the baby may not want to leave the womb, where it is most peaceful, but is obliged to when born. The desire to build a protective space reflects this home one cannot return to.

Primitive homes built as single spherical enclosures, with their top half bulging out of the earth like an inverted hollow, resemble the womb. The entrance, which stands out as the most striking architectural element, is an opening and a passage, symbolizing the return to a sacred place. Stairs, hallways, and doors are mementos of the natural passage out of the womb. Even in their most basic forms, these structural elements were decorated with utmost care and attention.9

Building a home is about creating a calm, peaceful and safe space that feels womblike. The home is a place of escape where we can shut the world out and listen to our own internal rhythm.10 It is a familiar space that belongs to each one of us, enhanced by secrecy, safety and intimacy on the one hand, and the individual’s life stages, memories and family stories on the other. All these values are embodied within the inside and the outside, or in the contradictions between inner and outer worlds.

The ‘unhomely’

If the home’s familiarity is unsettled, it can also be a place where we feel deeply alienated. Freud explains that the unheimlich, the uncanny, reaches beyond a simple sense of estrangement and relates to that which was once familiar. In other words, the familiar embodies and co-exists with its polar opposite.11

As an earlier-established literary, philosophical, aesthetic and psychological concept, the uncanny also inspired many literary works about the home. During the Romantic period, works such as those by Victor Hugo, Thomas de Quincey, Charles Nodier, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe depict the fall of the sacred home and elaborates upon the uncanny through a variety of themes, including being buried alive, the return of the buried, tensions between the inner and the outer, being caught between a sense of real terror and vague disquietude, the impossible yearning to go back to one’s origins, or the phantasy of the lost place of birth.

The longing for home, nostalgia, the death instinct, lack of mental clarity, recurrent episodes related to the same place and fear of castration are some of the motifs that transform what was once familiar into something alien and uncanny.12 The relationship between the self and the other is where the uncanny becomes most concentrated. The concept is explored through the ambiguity of boundaries and exchange of roles between ‘host and parasite’ or ‘master and slave’. The feeling reaches its climax when a stranger invades the home and family members are attacked. In this instance, the relationship between the internal and the external is completely reversed.13 The outside becomes safer, the home a place to escape from. Whether we leave the home obligingly or unwillingly, it will become either become a place to come back to or the eternal object of our yearning.

Many artists who work critically with space have focused on the uncanny character of the home. From the 1990s to the 2020s, nearly all of Rachel Whiteread’s work was house-themed (Image 1), Gordon Matta Clark physically cut through a building (1974) and Vito Acconci turned a house upside down (1984) – all are depictions of the uncanny home where the relationship between the internal and the external is reversed.

Rachel Whiteread, Internal Objects, 2020, Installation, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, 2021. © agreement with Varlik

Home in modern culture

Correlations between the home, the house and the act of dwelling highlight the phenomenon of ‘place’ and give rise to the notion that a home can be something other than a house. Modern architecture focuses on the production of rational housing or modern living units as design objects. Thus, throughout the twentieth century onwards, the home has been presented as a problem looking for solutions.

Modern design practices tend to ignore the feeling of homeliness. Living units can be and are designed but the home cannot actually be built. Rationalized and standardized modern housing proves incapable of meeting the modern individual’s need for a home. In attempting to escape from the crowds of modern life and an accompanying sense of the uncanny, individuals turn to the home. However, the design language of modern housing, typically fronted with glass facades, blurs the boundaries between the inner and the outer.

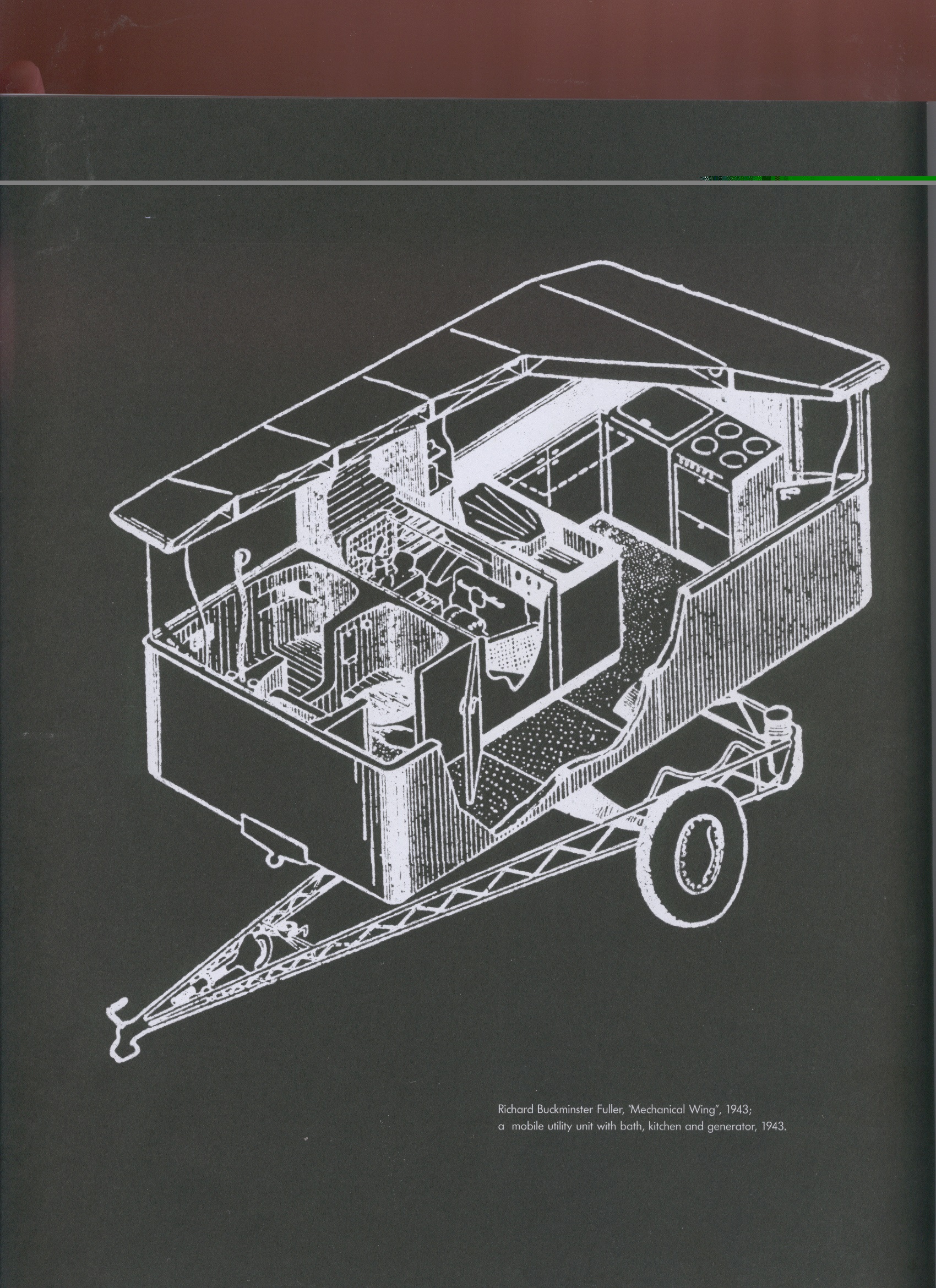

The spaces of modern housing are organized according to functionality. Based on concepts of flexibility and movement, they are divided into compressed and mechanized fixtures and functions such as eating, bathing, and resting (Image 2). Designs are minimal and focused on making the most use of small space, emphasizing movement and transience rather than putting down roots.

Richard Buckminster Fuller, Mechanical Wing, 1943 (Schwartz-Clauss 2002). © agreement with Varlik

The individual’s growing sense of alienation and loneliness in the big city, coupled with the transformation of the house into a laboratory for modern design, give rise to discourses on the longing for home. Theoretical studies in art, literature, philosophy and sociology represent the home as an object of nostalgia, a lost image, a myth.

The quarantine home

Did COVID-19 quarantine reunite us with the home we had been longing for while trying to keep up with the pace of modern life? During lockdowns, entire lives were lived at home without going outside. Standard acts of daily life such as eating and drinking, sleeping, keeping clean, working and resting were almost exclusively undertaken at home; we built our lives and ourselves around homely space. Home manifested as a constant state of indoor presence, or the literal act of looking outside from the inside.

The quarantine home emerged as a place of self-discovery and expression. We caught up with half-finished tasks and activities like finishing half-read books and completing creative projects. Quarantine was a time in which to finally engage with activities such as arts and sports previously marginalized. More time was spent watching films and documentaries, making jigsaw puzzles, playing video games. Interest and participation in online courses exploring domesticity and personal development rose. Online language courses become popular. Virtual museums receive many visitors. The virtual environment became, in itself, an instrument of exploration.

Elen Winata, Anonymous, Singapore, 2020/2021 (Artists share artworks made during the pandemic – CNN Style). © agreement with Varlik

Home was experienced quite intensely through routine activities that became experimental. People tried out recipes from around the world, baking bread, cakes, pastries. The results were photographed and posted online. With the advent of remote working, the home became the centre of cooking and eating three meals a day, needing a regular supply of food. All food items brought home from the outside were either disinfected, as described and propagated on social media, or stored away for a certain amount of time.

Home became a space to clean and organize yourself. Quarantine was the ideal time to clean nooks and crannies, organize cupboards, let go of old clothes and disused objects, and even organize digital archives.

Due to remote working, boundaries between the private and the public blurred or disintegrated altogether. Home enabled us to integrate with those people who accompanied us during these times.

Everything from domestic chores and routines to daydreams, creativity and ideas were expressed in the ‘quarantine home’. It provided us with a point of view of the world, and opportunities for self-expression, self-healing, self-improvement and artistic creations meant for sharing.

Art was made with whatever was to hand and became collaborative. Max Enrich’s Isolation Chair Challenge is a fine example, as it encouraged individuals to co-create. Another example is the Spanish artist Jaime Hayon who published one of his drawings online, asking followers to make print outs and colour them in as they wished, also allowing enough space for them to draw their own flags and write down the names of their countries. This work embodied many of the psychological and phenomenological meanings associated with home, compressed them and then let them circulate as artistic production.

Max Enrich, Isolation Chair, 2020/2021. © agreement with Varlik

Even though the house during quarantine fulfilled the internal functions of a home, it failed to fully support the home’s relevance to environment and place. This deficiency gave rise to discourses on longings for nature. The urban apartment compared unfavourably with the suburban house with garden. The city became a place to escape from, whereas the countryside was considered safe. The concept of the ideal home turned into that of an harmonious whole: earth, human and dwelling.14

Lockdowns and quarantine confirmed once again that a home is a lot more than a dwelling. It can only be truly understood and appreciated within the context of place and a relationship with terra firma. If anyone wants to understand the concept of home, an understanding not only of one’s self but also of one’s roots is the key. A place must ‘feel like home’ to become a home.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, The Concept of Dwelling: On the Way to Figurative Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1985), p. 9.

Norberg-Schulz, The Concept of Dwelling, p. 7.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Toronto: Saunders of Toronto, 1958; 1970), s. vii.

Ibid, p. 4.

Ibid, p. 45–47.

Ibid, p. 39.

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, translated and edited by James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 1955), s. 435.

Oliver Marc, Psychology of the House, trans. Jessie Wood (London: Thames and Hudson, 1972; 1977).

Idid, p. 9, 13-14.

Ibid, p. 14.

Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny (1919),” Papers on the Psychology of Art, Literature, Love, Religion. On Creativity and the Unconscious (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1958), pg. 122-24

Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992; 1994), pg. 17-45.

J. Hillis Miller, “The Critic as Host (1979)”, Critical Theory Since 1965, ed.s Hazard Adams and Leroy Searle (Florida: Florida State University Press, 1986), p. 453-54.

Marc, Psychology of the House, p. 121.

Published 10 May 2022

Original in English

Translated by

Asli Mertan

First published by Varlik 1/2022 (Turkish version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Varlik © Nilüfer Talu / Varlik / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Mineral rush

Topical: Critical raw materials

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.

Excitement over ‘rare’ elements

Julie Klinger in conversation with Misha Glenny

The race for green transition supplies is on. But where’s the thrill in metals, discreet and hidden yet widespread? Mining, intensive due to low concentrations, throws up waste elements like arsenic. Space cowboys and deep-sea dredgers contest environmental stability more than China’s monopoly, based on 40-years of involved processing. Health and recycling regulations are a must.

This article was first published in

This article was first published in