On the eve of municipal and presidential elections to be held in March and August 2014, the battle between a seething prime minister Recept Tayyip Erdogan and Fethullah Gülen continues. While the former has been weakened by corruption scandals linked to his entourage, Gülen’s movement stands accused of being behind the “plot” to oust the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi or AKP) regime – an accusation, which Gülen flatly denies. Spearheading a mysterious movement tinted with Sufism, posing as an advocate of interreligious dialogue and universal love, Gülen finds himself at the centre of one of Turkey’s most serious political crises since the 1980 coup.

The genesis of a rapid ascent

Fethullah Gülen’s “confraternity” is known as the “Hizmet”, the literal meaning of which is “at the service of others”. Originally from the Erzéroum province in East Anatolia, as a young Anatolian imam he first preached in Edirne in European Turkey, and then in the coastal town of Izmir, where he consolidated his support among a small community captivated by his charisma. Slowly but surely, the movement began its ascent, backing the military coup in 1980. After the military junta rose to power, its main agenda was to finally reconcile its vision of Islam (Sunni) with Turkish identity. This is how the well-known “Islamic-Turkish synthesis” (Türk-Islam sentezi) was born. From the onset, the imam’s violently anti-communist sermons inscribed themselves within the early twentieth-century tradition of Said Nursi (1876-1960). Nursi, an Islamic thinker of Kurdish origins, revolutionized the world of Turkish confraternities with his prolific works. However, despite fighting alongside Moustafa Kemal during the War of Independence, he rapidly fell into disgrace in the aftermath of the First World War.

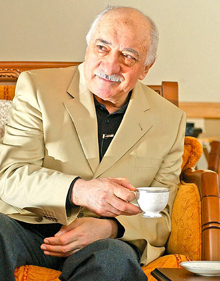

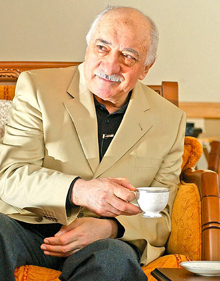

Fethullah Gülen, 2012. Photo: Diyar se. Source:Wikimedia

The imam grasped another opportunity in the early 1990s. In the aftermath of the USSR’s fragmentation, the independence of former Turkish-Soviet Republics gave rise to a massive expansion of the Gülenist Hizmet in this region due to the proliferation and expansion of educational establishments. This is how Gülen established close ties to Bülent Ecevit, the very secular social democratic prime minister of the time. Ecevit was anxious to profit from the Gülenist network in order to carve out a strategic space, which he would consider as his Asian sphere of influence. Again, it was Gülen who backed the army in its post-modern coup, which overthrew the Islamist prime minister Necmettin Erbakan in 1997. This pragmatic choice was motivated by survival, but also by an absolute refusal of all head-on polarization at the core of Turkish society.

A state within the state?

According to Tancrède Josseran, a specialist in contemporary Turkey, what is primarily at stake in the conflict between the secular and religious has always been, and remains, the monopoly over the education of future generations. The Gülen confraternity too intends to preserve a tool of faith that could eventually lead to the establishment of an elite. In fact, multiple factors favour the Hizmet’s progression. The State’s retreat in many domains followed by rising urbanization – a result of Anatolian migration – are contributing to develop a terrain in which Islamic-conservative civil society can thrive. By re-appropriating symbols of past glories, such as Ottomanism, the religious movement has carved out a path, which has led to the emergence of a conservative alter-modernity, according to Tancrède Josseran. Since modernity reflects an adherence to imported western science, it represents a historical opportunity for Turkey, which, in contrast to Europe, is portrayed as having preserved its entire spiritual force. Furthermore, the imam appears as an apostle of action, not least due to his systematic rejection of contemplative Sufi practices. Here, he builds on the basic consideration that technology and spirituality do not exclude one another.

Not happy to integrate himself into Turkey’s public domain without showing any party allegiance, the imam anticipates the formation of a new generation. Capable of regenerating Turkey, this elite generation will develop the country’s overall international visibility. Notably, this will be achieved via the Turkish Language Olympiads. In fact, from Morocco to Indonesia, passing through central Asia and America, Gülen’s adherents control more than 200 schools, seven universities and multiple university residences. Simultaneously, the movement is financed by hundreds of doctorate students who travel to Europe to complete their studies in prestigious Western universities. Inaugurated in 2007, a private college situated in the suburbs of Paris hosts 189 students, 70 per cent of whom are Franco-Turkish. Overall, there are almost two million youths enrolled in Gülen’s educational establishments. This does not include those enrolled in preparatory courses for entry competitions into higher-level education.

These establishments provide elitist and strict instruction, in which co-education is usually prohibited. As a sign of recognition, graduates in medicine, the police, military schools or the legal profession are obliged to donate their first salary to the order. What more could possibly be required to fuel the Kemalist establishment’s fears and phantoms, and the AKP’s too, which perceives a state within the state or, at worst, a sect with multiple ramifications? That numerous theses by sympathisers of the confraternity’s concern the influence of Catholic and Protestant churches in their respective societies sends a strong signal in this regard. Furthermore, lines of convergence between Opus Dei and the Hizmet, which perceives the former as a reference model, should not be excluded.

An actor of globalization

The Gülen movement has successfully managed to spin its web through the media level. The confraternity owns the Zaman daily, which prints a million copies and is also printed abroad in 13 different editions (notably in France). The imam’s supporters also manage multiple TV and radio channels (Samonyolu TV, Burç FM). Affiliated media groups have hired a host of journalists drawn from all parts of the Turkish political arena posing as champions of pluralism and freedom of expression. Indeed, Foreign Policy magazine declared Fethullah Gülen the world’s top public intellectual of 2008, drawing attention to his competence as a leader.

Seizing the opportunity provided by Turkey’s entry into a global market economy in the 1980s, Gülen’s supporters swiftly established themselves in the business world. They also benefit from their own employer’s union, the all-mighty TUSKON, which organizes official visits abroad and plays a critical role in implementing Turkish business strategies in Africa and the Middle East. Actively developing soft-power “Turkish style”, in contrast to other confraternities, interreligious dialogue is unique to the Hizmet. But according to Josseran, the movement’s ultimate goal is not to promote a meeting point with other religions nor to establish consensus or discuss theological principles, but rather to promote an encounter and consensus within itself.

Lines of convergence with the AKP

In 2002, the Gülenist community was in full swing. It actively campaigned for AKP by putting its media empire at the party’s disposal. Later, through foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu, the movement actively contributed to Turkey’s diplomatic expansion. Indeed, by utilizing its educational web, the Gülen movement operated as a channel of influence not only in Ankara’s politics, but also for Washington in the context of Russia’s former central Asian sphere of influence. Viewing these Turkish missionaries with suspicion, Moscow proceeded to shut down facilities and expel teachers in the Republics of Bashkortostan and Tatarstan, both members of the Russian Federation. Internally, Gülen was quick to maintain impartiality with political parties in his own country. Inspired by the positive secularism applied in the US, it backed AKP from the onset by seeing Erdogan as a pro-European and modern democrat. On the other hand, the movement blasted the Kemalists and, through a semantic tour de force, went as far as defining them as “secular fundamentalists”.

Far from constituting a homogenous entity, AKP is traversed by multiple trends. In a personal capacity, Erdogan has close ties to the Naqshbandi Sufi confraternity, while the foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu maintains strong links to the Muslim Brotherhood. Moreover, staunch Gülenist enemies exist within government. These include the president of the national assembly, Cemil Ciçek and the vice prime minister, Besir Atalay.

On a moral plane, as well as in terms of devising a societal project, members of the Gülen cemaat (community) are no different to those of the AKP. They share the same conservative frame of reference: prohibition of alcohol, cigarettes and abstinence from sexual relations outside of marriage. Imam Gülen’s followers are invited to observe its strict code of impeccable behaviour and expected to donate part of their salaries to the community. Beneath the obvious facade of dialogue with the country’s non-Turkish elements (Armenians and Kurds, among others), Gülenists remain staunchly marked by Turkish nationalism. In this respect, they share a similar approach to the AKP and other rightwing parties, one marked by inflexibility as regards several “red lines”: including those that relate to granting the Kurds greater autonomy or recognizing the Armenian Genocide.

A latent struggle on the eve of two elections

In recent months, Turkey is in the grips of a very real, latent civil conflict. In order to deter a full-blown war, the government has shut down the private schools (dershane) from which the Gülenist movement draws much of its support.

A wave of accusations and the imprisonment of about ten bosses, entrepreneurs and elected politicians close to the prime minister on charges of corruption, fraud and money-laundering has infuriated Erdogan. Accusing the Gülenist confraternity for hatching the “plot”, he underlines how entire sections of the judicial and police administration are infiltrated by its members and Gülenist sympathizers.

Never entirely concealed, the divide between the two main currents of Turkish Sunni Islam has emerged into broad daylight. On one side, followers of imam Fethullah Gülen – exiled to the United States in 1999 for anti-secular activities – unconditionally support Turkey’s position in the North Atlantic Alliance and the preservation of good relations with Israel. On the other, Erdogan’s supporters – adherents of ex-prime minister Necmettin Erkaban’s Milli Görüs Islamist movement – are making no attempt to conceal their anti-western stance. Already in 2010, on the occasion of the Gaza Freedom Flotilla, conflict arose in relation to Israeli-Turkish relations, and resulted in Gülen condemning the blockade. Regardless of whether the confraternity’s links extend beyond party politics, they have currently shifted their attention to the AKP. The anti-corruption campaign released following the resignation of an AKP deputy and numerous arrests bear witness to a permanent divide.

Several hypotheses are being advanced in this tug of war, whose outcome is as yet unknown. There may be a possible formation of a new political party capable of rallying dissatisfied Erdogan supporters around imam Gülen. Yet, at seventy-three years of age, will he be capable of donning the robes of prime minister? The fact remains, that this struggle of many faces is being played out behind the scenes of Turkey’s economy. It is a struggle between different structures maintaining ties of allegiance to the prime minister or to cemaat sympathizers, and one capable of compromising the achievements of a decade of exceptional growth.

Further reading

Hakan Yavuz, Toward an Islamic Enlightenment: The Gülen Movement, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Tancrède Josseran, La nouvelle puissance turque, Ellipses, 2011.

Thierry Zarcone, La Turquie moderne et l’Islam, Flammarion, 2004.