The populist radical Right (PRR) in Europe, which is openly eurosceptic or euro-rejectionist and promotes a nativist ideology (“Our people first!”), is perceived as a constant and permanent threat to European cohesion and solidarity, one of the EU’s driving concepts. Upon closer scrutiny, in this era of crisis, when “solidarity” has been abandoned by domestic and European politicians, that same solidarity appears to be key to the persistence and potential of the PRR’s future success.

The European Union flag in the European Parliament in Strasbourg. Photo: European Union/European Parliament. Source:Flickr

Rationale behind the success of the populist radical Right

The re-activation of populist right radicals in the 1980s and 1990s was preceded by the oil crises and the eventual collapse of the social-democratic welfare dream, and enabled by a general shift in social cleavages, as well as the deterioration of “traditional politics”. By the turn of the twenty first century, it had become clear that many of these parties were here to stay. Numerous scholars and publicists reflected on the question: what led to the success of the populist radical Right?

To get a full picture we need to look carefully at both sides of the coin, since academic research on the topic distinguishes between demand-side explanations and supply-side ones. In both cases, several crucial values and principles of liberal democracy have been redefined by PRR leaders and successfully exploited in electoral competition. One of these is “solidarity”. Demand-side factors behind the PRR’s success concern voters and supporters, along with the issues fuelling their grievances. What happens in social stratification, economics and politics that encourages people to back the PRR?

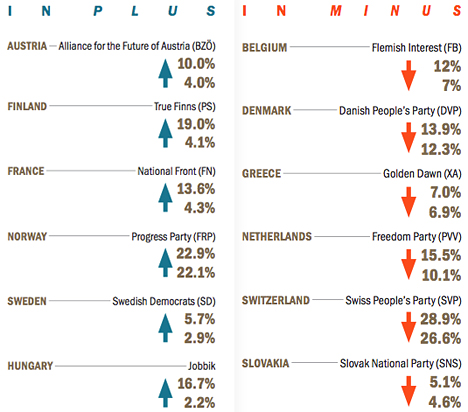

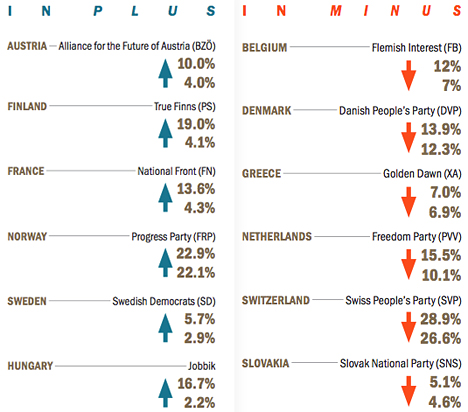

Research concerning social structure underlines that the most fertile ground for the PRR is found among the blue-collar lower-middle class and young male workers and entrepreneurs who, statistically, are most likely to support the PRR. When it comes to economics, the answer frequently given is increasing unemployment and high immigration rates. In politics, what gives rise to the venting of these grievances is general distrust of or disenchantment with a mainstream politics that, in the eyes of society, is ineffective or otherwise fails to meet demands. In other words, having experienced the repercussions of the 2008 crisis, Europe became extremely fertile ground for PRR sentiments, at least when it comes to electorates; however, electoral results do not support this thesis. In the last few years, voting trends have been more ambiguous than the thesis might have suggested.

Shift in the recent electoral results of the Populist Radical Right Parties (PRR) in the EU: Percentage of seats.

The other side of the coin is missing: the PRR’s fate in parliaments is also shaped by supply-side factors concerning the political or institutional contexts in which these parties operate and how mainstream parties, media and the international environment facilitate or hinder their progress. Generally speaking, what matters most is electoral laws and the strategies adopted by other political parties and/or the media. Thus, the most favourable setting for new entrants would be a proportional electoral system with multiple-seat voting districts and no thresholds, with major parties open to cooperation with the radicals in the government.

Lastly, there are the strategies towards radicals pursued by other actors such as parties and courts. These vary from adaptation (Austria, Slovakia, Poland, Switzerland, and Hungary) and fractionalization to complete isolation (witness the cordon sanitaire approach in Flanders, Belgium or Sweden).

Taken together, not only popular grievances but also the stance taken by the mainstream remain crucial in shaping the PRR’s success so far. The question remains: does the PRR still need mainstream politics in order to expand?

The new wave of radicalism is something we are experiencing here and now as a result of the

crisis that began in 2008, which burst not only the housing bubble but also a political one.

Many accounts in both academia and the media warn of the growing influence of radical right parties, but until now analyses of direct effects as regards parties, policies and societies show the successes of the far Right to have been limited. As Cass Mudde concludes: “The effects are largely limited to the broader immigration issue, and even here populist radical right parties should be seen as catalysts rather than initiators, who are neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the introduction of stricter immigration policies.”. Shall its limited impact be read as a PRR weakness? This leads us back to the question of “solidarity” as populist right radicals’ modus operandi. That which at first glance seems irrational is exploited on a regular basis in the practice of these parties and organizations, and should be considered the main factor that appeals to the demand-side (supporters), at the same time as weakening the supply-side (state institutions).

Nativism: Solidarity with “our people”

The populist radical Right in Europe is a product and an agent of structural changes in European societies. A form of “solidarity” based on an anti-establishment stance and nativism can be seen as the ideological core of these organizations. It needs to be underlined that the “solidarity” concept discussed here contradicts the European understanding of the term. The “solidarity” concept discussed here is based on ethnocentrism, in which demands for a favoured status for a native (“own”, “pure”) population are mixed with xenophobia. One of the most direct visualizations of this concept was used in Switzerland during the electoral campaign of 2008. The PRR Swiss People’s Party campaigned with posters on which one black sheep was being literally kicked out of a herd of white ones. The poster has been re-used by its German counterpart – the NPD.

Swiss People’s Party campaign material.

This topic stands out in the PRR’s agenda and overshadows European discourse on immigration quotas, asylum, integration requirements and citizenship laws. The effects are two-fold. In Denmark, the Netherlands, and Italy, these parties rose by filling in the niche in political discourse and pursuing restrictions in immigration policies. After taking on the tough-on-immigration agenda, the Swiss People’s Party has remained on the Swiss Federal Council and gained an extra seat. Even when not in power, the populist Right still strongly influences the public discourse on immigration. That is the case in France, where politicians like Sarkozy integrated elements of their discourse (during a presidential talk in 2007, for example). Martin Schain has observed that the Front National presence “resulted in redefinition of the issue of immigration in national politics, from a labour market problem, to a problem of integration and national identity, to problems of education, housing, law and order, and citizenship”. This results in chauvinism when it comes to welfare policy. In general, the PRR calls for “solidarity” among an exclusive group of citizens, and for a national (that is, citizens only) preference as regards social benefits and employment.

German NPD campaign material.

Central and eastern European cases, which differ in terms of cultural heterogeneity, do not differ much when it comes to the rationale behind them: an ethnically pure population in the eyes of radicals is faced with non-native elements like historical minorities (Jews), contemporary ethnic minorities (Roma people) or inhabitants of non-Caucasian origin, and deserves protection: therefore, the concept of “solidarity with our people” is being used again.

Escaping the box

Three decades of populist radical right parties in Europe did not end in the demise of liberal democracies, nor stop post-communist ones from integration with EU structures. Indeed, nomen est omen, radical scenarios would be the best indicators of the direct influence of the radical Right’s vision of “solidarity”. Direct effects, however, are also accompanied by indirect ones, and here arises the question of bridging the gap in solidarity left by mainstream politics. And here, the disillusionment with politicians and politics as a whole, especially among the younger generations, has to be taken into consideration.

We can observe in recent years that some of the successful PRR parties have grown up. They have learned from their mistakes and have often gained more experience at the sub-national level, while cooperating in the European Parliament or organizing international meetings and workshops.

As a result, radical right organizations are thinking “out of the box” and becoming more sophisticated. This can be said of the BZÖ in Austria (the heir of Haider’s FPÖ), the Freedom Party in the Netherlands (successor to the Pim Fortyun List), Jobbik in Hungary, and the National Movement in Poland. The channels of influence become diverted and political parties surrounded by affiliated organizations with stronger roots, especially in the young groups of society. And this is where the idea of solidarity pops up again. The National Movement is consistently presented by its leaders as a social, grassroots movement organized and developed at different levels, and embracing different forms. The new vision of National Movement leader Robert Winnicki is “to build the social movement that mobilizes the nation, organizes it and overthrows the round-table republic.” This is a case of the innovative strategy of the radical Right altering type of activism in which political parties engage. Indeed, since its inception, the National Movement’s strategy is to work on the ground and utilize existing local resources.

In the case of successor organizations, the concept of internal solidarity stands up. Organizations that are centralized and led by charismatic leaders build structures based on a sense of group alienation on the one hand and internal loyalty on the other. What sympathizers are offered is a peculiar way of re-building solidarity and national/ethnic identity. One needs to realize that this vision is also inviting as it goes back to the nineteenth century and a homogenous, nationally-oriented vision of communities. This, in an era of globalization and permanent change, could be perceived as the only possible ground for solidarity in practice. The populist Right, historically and contemporaneously, relies on a specific form of “solidarity”, on the basis of which, it gradually builds in terms of social and political relevance. This is the case in “mature” democracies like France, the Netherlands and Denmark, as well as the new or, as Huntington puts it, third-wave democracies (that is, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland). This notion is especially important in the (almost) post-crisis EU, where the esprit de corps urgently needs to be rethought, discussed, and implemented at both domestic and European levels.

The results of domestic politicians and EU institutions abandoning this element of public discourse and policy can be seen in Greece, where, in the name of “solidarity”, Golden Dawn activists violently “handle the immigration problem”, and, step-by-step, redefine one of the fundamental EU principles and benefit accordingly. Leaving this concept unclear, and questions of the future of “solidarity” unanswered, can cost societies, as well as Europe, more than expected.