Diaries and memoirs of the Maidan

Ukraine from November 2013 to February 2014

In these impressions of the Maidan protests collected by Timothy Snyder and Tatiana Zhurzhenko, one hears the voices of those who witnessed history in the making. The role of civil society and the Russian-speaking middle class, as well as individual existential decisions, also come to the fore.

Introduction

These texts concern the protests in Ukraine against Viktor Yanukovych’s regime between November 2013 and February 2014. Most of them were written by people who protested on the central square of Kyiv, Independence Square, known in Ukrainian as the Maidan. The term Maidan stands not only for the place but for the protests themselves. The turning points that appear in these recollections are the beginnings of the pro-European protests on 21 November 2013, the beatings of student protestors on the night of 29 November, the attempt by riot police to clear the main square of Kyiv (the Maidan) on the night of 10 December, the laws against civil society of 16 January 2014 and the violence that followed, the failure of Yanukovych to compromise in talks with the parliamentary opposition on 19 January and the mass shootings of protestors and revolution of 20 February.

Kyiv, 20 February 2014. Photo: Roman Mikhailiuk. Source:Shutterstock

These texts were either written contemporary to the events they describe or as a response to a solicitation in late March 2014. The former texts bear dates before April 2013, the latter bear dates in April 2014. The question was formulated as a request to record an experience relating to the Maidan between November 2013 and February 2014. No further narrative guidance was given; and there was no prior contact with the authors of the unsolicited texts, the ones dated before April. The authors focused (or were asked to focus) on what they saw, experienced and thought themselves.

International and even domestic politics are very much in the background. We do not see here, and cannot see here, the way that Russian policy escalated the situation and created the conditions for the revolution: first by providing Ukraine’s president with the promise of a major loan and lower gas prices as a way to prevent an association agreement with the European Union in November, then by providing the model and no doubt also the encouragement for the dictatorship laws of January, all the while by making the disbursement of the money dependent upon the clearing of the Maidan. The mass shooting of 20 February followed constant consultations between Yanukovych and Russian authorities, as well as a public announcement by the Russian government that money would be forthcoming as soon as order was restored.

Likewise there are only hints of the domestic political situation. Yanukovych had established an authoritarian regime in which parliamentary opposition existed but which was essentially powerless. Thus the protestors generally and increasingly did not see the leaders of the opposition parties as their representatives. The parliamentary opposition called for calm but during the protests had nothing to offer in return. This changed only after 20 February. After the sniper massacre of that day, Yanukovych fled to Russia, and power returned from the streets to parliament.

The rest is well known: Russia’s President Vladimir Putin asked for and received authorization from the Russian parliament to invade all of Ukraine and alter its social and political structure. Russia in fact invaded Crimea, which distracted attention from the catastrophe of its previous Ukrainian policy, which resulted in a revolution and the formation of a pro-Western government. This government functions under new constitutional arrangements, with limited power for the president and under the watchful eye of protestors. Russian policy, although it brought about the exact opposite of what it intended during these months, has largely succeeded in turning the protests themselves into elements in an information war, and the people involved into symbols of an ideological competition.

Ukrainians on the Maidan had their own concerns, which do emerge in these sources, and which generally enlarge or rather defy the categories that were then and later imposed upon them from the outside. In these texts, which come largely from scholars and professionals, three interesting themes emerge: the strong and probably decisive presence of the Russian-speaking middle classes in the Maidan in Kyiv; the experience of what in the eastern Europe of the 1970s and 1980s was called civil society; and moments of individual existential decisions (sometimes explicitly formulated as such) that were experienced as defining individual identity against an absurd world of violence. Certain obsessions of the western press, such as language and ethnicity, are present, but perhaps not in the expected form. That the protestors spoke both Russian and Ukrainian and came from multiple national backgrounds emerges only incidentally; this is something that at the time was simply taken for granted.

The solicitation and translation were carried out by Timothy Snyder and Tatiana Zhurzhenko, with the exception of the text by Slawomir Sierakowski, which was translated by Marysia Blackwood. A very few brief editorial notes that provide clarifying context are in brackets. Every attempt was made to preserve the freshness of the original style.

Timothy Snyder and Tatiana Zhurzhenko, 8 April 2014

Nataliya Stelmakh, written 4 April 2014, in English

Fate intervened to ensure that I would be on the Euromaidan. In November, I had taken on the job of managing the shopping centre right under the Maidan.

The shopping center, a place that was once coveted by foreign investors, was soon blocked by the barricades and tents of people fighting against a regime of unprecedented corruption. We knew something was about to happen on 29 November, the night when the kids were violently beaten by riot police. Our security personnel noticed unusually large numbers of riot police gathering and overheard their discussions.

In the morning we read the news that the students had been beaten and their demonstration dispersed. I rushed to St. Michael’s Cathedral where some of the protesters were hiding. On the square near the church, about thirty people gave speeches and somehow the smell of revolution was in the air. I got involved.

I want to convey the things that surprised me.

Maidan Shock #1. Within two days other volunteers and I were able to collect in hryvnia the equivalent of about 40,000 dollars in cash from simple residents of Kyiv. I laugh when I read stories about how people were paid to be on Maidan. In fact, people donated money to help others on the Maidan. What started as fundraising for wounded people ended up as fundraising for revolution. Grannies gave us the equivalent of fifty dollars (about half of their monthly pension) saying “For your victory, kids!” Though we tried to tell them we did not accept money from elderly people, they angrily insisted. Sometimes we were given candy, apples, soup or warm socks.

Maidan Shock #2. Already on 30 November, the very first day of the large and active protests, reporters from four Russian channels approached us, all of them asking who organized us and whether we got help from the United States. They simply could not grasp that we ourselves organized ourselves and were ourselves in charge the process. Kyivans took the initiative: to run the camp, to be head of security, to be head of food supplies collection.

Maidin Shock #3. The first clashes on Bankova Street on the 1 December, when nine people were detained and summoned to court the following day. Their assigned lawyers were afraid to represent them. We had to shout on Facebook – who can go to court immediately to defend them? As we expected, the police did not rush to interview witnesses who saw the provocateurs at work that day.

Kyiv, 8 December 2013. Activists assist man wounded in a clash with the Berkut. Photo: Roman Mikhailiuk. Source:Shutterstock

Maidan Shock #4. When on 10 December the authorities tried to clear Maidan for the first time. With armored vehicles and thousands of riot police the authorities evacuated all the businesses and governmental buildings around by 4pm. As we were leaving the Maidan that day I saw no fear in the eyes of the protesters; they looked sharp and determined. They knew that their mission was much more important and holy than their lives. They were shaving and putting on clean clothes in case they should die that night.

Maidan Shock #5. A first phone call at one in the morning: “They are attacking!” Another call in some minutes from a former colleague, a top manager who speaks several languages: “Where do you have emergency entrances in the shopping centre? Can they run and hide there if riot police manage to enter the Maidan?” Her husband, a corporate lawyer for a leading oil distribution company in Ukraine, together with my former subordinate, the director of an investment department, were on the Maidan then, though the risk of being beaten up was the highest ever.

These are the people would soon be called “neo-fascists” and “neo-Nazis” by the western press.

Ivan Suharenko, 11 December 2013, written in Russian

It happened that last night I was among the defenders of barricades on Instytutska Street [on the night of 10 December, when the Berkut riot police tried to clear the Maidan]. I am not really a revolutionary and the last time I demonstrated any social initiative was in 2004. I cannot stand large crowds. But this was a special situation. I had to suppress my claustrophobia. But I do not want to talk about myself or about crowds in general. I want to talk about our crowd.

During the fight with Berkut on the Maidan I drew some conclusions that I would like to share with you. The Maidan crowd is good, kind, decent. Before my eyes our crowd took better care of Berket policemen than it did of its own people. When Berket men were surrounded, the crowd opened a path for them so that they could return safely to their own people. Everyone who fell down, whether it was a policeman or a demonstrator, was helped to stand up again, despite the awful crush of people. When I fell down at the barricades I experienced this myself.

The Maidan crowd ready for bloodless resistance. I would not call it peaceful resistance, but rather bloodless resistance. Those who were longing for blood were quickly excluded. Those people who had the idea to disarm the Berkut policemen and take their shields and helmets were quickly calmed by others – and the police were given back their things. No one was allowed to take clubs away from the policemen.

The Maidan Crowd has some internal mechanisms that allow it to regulate the power and the direction of its pressure.

The Maidan Crowd is tolerant on the language issue. I never heard any discussions about this question.

All of these are arguments in favour of my thesis that the Maidan Crowd is indeed intelligent and also humane. I do not regret becoming a part of it.

One more thing before I forget. If you have several thousand people behind you and you press against a metal shield with your hand, it will yield. Today we were able to bend their shields!

Fedor Sivtsov, 11 December 2013, written in Russian

[Note: This text was written immediately after the failed attempt by Berkut to clear the Maidan.]

Three things happened to me today.

1. I began to believe in God.

When the Berkut broke through the barricades and began to push people back, children were brought to the stage, and those who did not fit on the stage were put in the middle of the circle. And people were praying and trying with the last ounce of their strength not to cry out of helplessness and fear. And then suddenly the church bells began to peal in the night. And these bells brought hope. And at that moment I began to believe in God.

2. I became a nationalist.

I saw, beyond Berkut, the soldiers of the interior ministry, my compatriots, people who were supposed to represent and defend the law in my country. They were fulfilling an idiotic and monstrous order that was in the interest of only one person – the president of a neighbouring country, because our president is not recognized here by anyone any longer. These soldiers were pushing the peaceful demonstrators, children, women, older people, and they did not care what they were doing.

And then I heard a cry from the stage: “They heard us! People are coming to us from all over Kyiv!” And then I looked back and saw an endless stream of people, Ukrainians who care about the fate of their fellow citizens. Ordinary fellow citizens who came to protect peaceful people. At that moment I became a nationalist.

3. I freed myself from fear.

The police and soldiers encircled the square and started pushing us. But they were not strong enough, and we pushed back; and even if we could not move them we could at least hold back the flood of beasts. At that moment I freed myself from fear.

Believe me, I am far from being the most fearless person in this country. But today I will go to Maidan again. For this night, and for these people, for this feeling of pride in being a single and united people – and for the dignity that we defended.

Andrij Bondar, 12 December 2013, written in Ukrainian

Last night on the Maidan a very simple thing was revealed. The people who arose against the authorities were those who learned in the last 22 years to live and to survive without the state. These people needed very little from the state – security, fair taxation, understandable rules of the game, the rule of law and, of course, their freedoms. They are not interested in the government as such. They can live peacefully without a government. It is better for them to live without any government than with a government that cannot ensure the atmosphere in which they can do everything themselves.

On the Maidan a Ukrainian civil society of incredible self-organization and solidarity is thriving. On the one hand, this society is internally differentiated: by ideology, language, culture, religion and class, but on the other hand it is united by certain elementary sentiments. We do not need your permission! We are not going to ask you for something! We are not afraid of you! We will do everything ourselves.

This is our exemplary Maidan. We have given ourselves permission to be free. Politicians, real and potential, who understand that one should begin from these basic principles of organization and social life, will have a future in the construction of the future of the country.

It looks like a union of individualists in a very strange anarcho-liberal-nationalist atmosphere, in which, to repeat, not much is needed. These individualists do not need much. They need freedom. The slogan “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes” is understood by each person in his or her own way.

The Maidan today is a laboratory of the social contract. The social contract is what the broad masses of Ukrainian society have not had for so many years. We do not need a Father or a Leader. We need liberty. Without liberty there will be no reform and no modernization.

Kyiv, 12 December 2013. Photo: badahos. Source:Shutterstock

Ukrainians are building tents and barricades to defend themselves from the Berkut police so that they do not have to dig trenches. This is also their liberty. This is the real civilizational choice, this is what Europe means. A union of IT specialists from Dnipropetrovsk and a Hutsul shepherd, an Odessa mathematician and a Kyiv businessman, a translator from Lviv and a Tatar peasant from Crimea. The union of the self-sufficient.

Sergei Gusovsky, 13 December 2013, written in Russian

My dear friends, you might have noticed that since the end of November I have not been writing about wine festivals, special menus and other pleasures of bourgeois life. This does not mean that my restaurant has ceased to welcome guests. I just think that today, it is simply wrong to fill the ether with marketing.

Blood was spilled, innocent people were sent to prison, and hordes of special police units are on the streets. From the perspective of an ordinary person this is a nightmare that came true. Ukraine and all of its inhabitants, from the beggars to the president, have crossed the Rubicon. That is, everyone has passed his or her own individual, private Rubicon. None of us can return to the situation of two or three weeks ago. The last drop of our patience was the first drop of blood spilled on the Maidan.

What is the Maidan today? It is a city of utopia. It is protected by defensive fortifications and inside govern unwritten laws that allow you to feel that you are an absolutely free person. If you want to work, then by all means! If you are hungry, you are welcome to eat. If you are freezing, you can find warmth. If you are done sitting next to the bonfire, then you can get back to work. If you are tired, go to sleep. When you awaken again, you are greeted again in this honest city. The city is as primitive as it is holy. If you have not been to the Maidan yet, you should definitely come. It is not necessary to adorn yourself with ribbons to wave a flag. Just come and see. Be guests of this incredible city. But beware! It is very likely that once you have seen it you will decide to become one of its citizens.

You know, I would like to believe that today’s Maidan is an embryo from which the new Ukraine will develop. Not in a month and not in a year, but it will develop. Definitely. Because this city of utopia exists. The Maidan is an actually functioning and complete organism that gives much more than it receives. It is a city that gives its citizens not only energy and power but a very special belief in the triumph of justice and honour. It is precisely this belief that should become the ideological basis of the new political order. Justice and honour will be our criteria as we observe those to whom we delegate the power to manage our country.

Aleksandra Kovaleva, 12 December 2013, written in Russian

To all of those who complain about the impossibility of bringing their children to the Maidan to see the Christmas tree. Let me explain in a simple way.

No one is stopping you. The way is open. The Christmas tree is there. One million people decorated it. If you care about your children, bring them to the Maidan now. The official (and commercial) Christmas tree of Kyiv your children can see any year. But a Christmas tree such as the one on the Maidan this year they will never see again.

Today is December 12 and the barricades rise to the sky, there are huge tents, and iron cauldrons, and the smell of bonfires. Veterans walk by in their Afghan hats, priests in camouflage, girls with flowers in their hair, old men with long white beards, and a man in a Superman costume. Here the nice older folks in orange helmets offer tea and oranges and cookies. Here every other person has a piece of candy in his pocket for his neighbour.

The people here on the Maidan sing and dance, and then climb the barricades with flags. In the evenings, they turn on their little flashlights and sing one song together.

Here people work together, without being paid, just because this is the right way to do things. They clean streets. They repair broken windows. They share scarves and gloves. Here old men and young boys from all parts of the country, perhaps naively but certainly honestly, fight for their dignity.

Before Mordor returns, take your children to see the Christmas tree. It is already decorated. We trimmed our tree much more quickly than the mayor did. And by the way, it costs the city nothing. The snow has been cleared from the streets. The Maidan is now cleaner than any other part of the city of Kyiv. People did this themselves, without being paid. This is our gift to the city. Since it is a gift, we do not need to be thanked.

Please keep one thing in mind. Time will put everything in its proper place. In ten years your child will ask you: “Why, Papa, didn’t you take me to this famous revolutionary Christmas of 2013, which would have aroused my imagination, encouraged my civic identity, and developed my understanding of human values?” And what will you answer? That ten years ago you did not share someone’s political attitudes?

Volodymyr Sklokin, 4 April 2014, written in Ukrainian

In the second half of December and in the beginning of January I managed to return to Ukraine. I spent a few days on the Maidans in Lviv and Kyiv, and then more than two weeks in my home city of Kharkiv. The situation in Lviv and Kyiv seemed to me then to be rather calm and paradoxically I felt the atmosphere of the Maidan in Kharkiv, which might at first seem to be far away from the central events of the Euro-Revolution.

The Euromaidan in Kharkiv met beginning at the end of November at 6pm each evening, and at noon on Sundays, near the Shevchenko monument. During most of the active phase of the revolution, these gatherings were not especially numerous, ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand people.

Truly massive gatherings in Kharkiv, bringing together tens of thousands of people, took place only after the mass shootings in Kyiv of 18-20 February and the threat of separatism in the eastern and southern regions of the country after the flight of Yanukovych from Kyiv.

That said, even the relatively small gatherings, which did not even consider such goals as occupying government buildings, clearly irritated the local authorities. The two most important figures were the odious representatives of the Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, Hennadiy Kernes and Mykhailo Dobkin.

At some point in the middle of December, having temporarily abandoned the notion of destroying the Maidan by force, central and regional authorities adopted instead the tactic of individual terror against Euromaidan activists, expecting in this way to neutralize the leaders and frighten the rest. In the first stage, this terror was perhaps most pronounced in Kharkiv. From the middle of December through the end of the month, the cars of at least five activists were burned. These were usually people who had been bringing food, tea and leaflets for the activists. There was an attack on the Euromaidan headquarters on Rymars’ka Street. The printing press where revolutionary pamphlets were printed was also burned down.

I remember how all of this was announced at the gatherings and how it brought forth outrage as well as ironic jokes about the Kharkiv authorities. But there was at the time no fear. A true shock and one of the turning points of the revolution came however on the evening of 24 December, Christmas Eve by the Catholic reckoning. On that very day came the assault upon Dmytro Pylypets. As he was returning home from a gathering he was attacked by two unknown men and was wounded twelve times by their knives. On the same day in Kyiv, the well-known journalist Tetiana Chornovil was also attacked.

Because of the holidays I did not watch the news on 24 or 25 December, and so I did not know what happened. I remember how as I left church on the 25th with my wife we saw our good friend Vasyl Riabok, one of the coordinators of the Kharkiv Euromaidan and the leader of the rock group Papa Karlo. Vasyl, pale and nervous, offered us no Christmas greetings, but instead at once asked if we had heard the news. We learned from him then what had happened to Pylypets. (At the time it was unknown whether Pylypets would survive, but fortunately his numerous wounds were not fatal, and he was able to return to the Euromaidan within a few weeks.) Vasyl told us that he had been informed that further attacks on activists and provocations would follow. All coordinators were to take extra precautions and move about only in groups. But the meetings would take place as before.

The first few hours after our conversation with Vasyl were for me a time of very complicated considerations and doubts. I very clearly remember the shock that came from understanding that the authorities had crossed a Rubicon. It was one thing to ban the meetings, to burn cars, to attack empty offices. It was quite another to physically attack individuals.

Kharkiv, 2 March 2014. Funeral of a Euromaidan activist killed in Kyiv. Photo: Mykhaylo Palinchak. Source:Shutterstock

I think that it was in those hours that I experienced what at one time or another every participant in a revolution experiences. My reason said that resistance made no sense, that it would make more sense to await a better moment to change the regime. I asked myself what we could possibly do against a regime that controlled the militia and was willing to behave criminally. And what could be done in Kharkiv, where the opposition was supported by only about 30-40 per cent of the population? My reason said: better not to do anything, better not to yield to those provocations. And then I asked myself how I would look in the eyes of Vasyl Riabok if I did not come to the meeting that day. How would we look to one another if we all gave up?

And at that moment the most important argument became my realization that I gave up then, I would no longer be myself, but someone else. That to concede at that moment would be to resign from something very important, something that other activists called dignity, and that I, using a more theoretical language, called subjectivity. So there was this sense that if I wanted to remain myself, I had to go to the meeting that day and continue the struggle, not thinking about the consequences. That to behave otherwise was simply not possible.

A very large number of people gathered on the evening of 25 December at the Shevchenko monument, and even more came the following Sunday.

The dominant emotion in those days was not fear but anger. The calculations of the authorities were not borne out, people did not give into fear, but rather hardened themselves. On the 25th after the meeting I sat with several friends at home, making tea and telling jokes about the stupidity of our government. At that moment I was sure that despite everything we would be victorious in the end.

Iryna Vushko, 4 April 2014, written in English

I flew to Kyiv from New York on December 24. Coming originally from Lviv, I had become accustomed to thinking of Kyiv as a city of cruel businesses, unrealistic prices, as more of a Darwinian jungle than any other place I have seen, including New York. In December, a new image of Kyiv started to sink in: that of courage and new men.

The Kyiv I discovered for myself in late December was nothing like it had looked on my computer screen in New York: the city was living its own life, traffic jams packed with cars few in New York could afford and dark streets – a sharp contrast to the Christmas lights of New York. The Maidan that had looked so exciting on the Internet appeared rather gloomy in real life, an accumulation of seemingly random people living a life that resembled the Middle Ages more than the twenty-first century.

This sense of gloom disappeared together with the jetlag, but the feeling of senselessness remained – hundreds and thousands of people putting their lives on hold, spending days and nights on the square with no clear purpose and no end in sight. I was in Kyiv again on 16 January, when the draconian laws were passed and when the sense of gloom seemed overwhelming.

It was only after the killings of 20 February and Yanukovych’s escape that I could grasp the logic behind it all. Corruption had become a norm in that part of the world, but I could never imagine the sheer extent of it – human beings living the lives of immortals. By then, I had become an extremist. I had been saying that twenty years with Yanukovych was nothing compared to a war; that none of us remembered a war in our lifetimes; that we could not possibly imagine the devastations that it may incur.

By January, I no longer believed that dancing and singing on Maidan could have any results whatsoever. We knew Yanukovych would not resign voluntarily. I accepted violence as a norm, suspecting that things could get much worse very soon.

Kyiv, 23 January 2014. Photo: Liukov. Source:Shutterstock

In late January, back in New York, I met Ukrainians who became stranded in the city and who have done more for the cause than all the others I had known before combined. For the first time in over ten years, I switched to Russian in my everyday communication: unlike myself, they came from the East, and spoke Ukrainian with some difficulties. Some of them could not return to Ukraine. Some had been the masterminds of the Maidan, playing a more important role than hundreds or thousands of west Ukrainians spending days and nights in the tents.

Some of those living in the tents had little to lose: the peasants in between the seasons living a life not so different than the one they would have been leading back at home, in the village. For some, as we learnt in retrospect, Maidan was almost an escape from impoverished homes. But the people who were much better off – many of them Russian speakers – were less visible to the public. Some of them sacrificed their careers, homes, putting everything on the line to an extent that can be hard to grasp.

February was the worst. On 20 February came the killings that few of us could have imagined before. Then came the first serious international reaction, and with it another shock. As I watched death and burials, in real time, I could not believe the response of so many in the West: discussing language politics, dress codes and blaming it all on the extremists, during the peak of killings. I was one of many dubbed “Bandera children.”

The condescending attitudes and the sheer lack of empathy still keeps me awake at nights.

Slawomir Sierakowski, 7 April 2014, written in Polish

The special atmosphere that accompanies revolution is something historians note in books such as those on Solidarity. The most common adjectives are those such as: unique, exceptional, heated, exalted. This is a period of “Star Time,” as Jacek Kuron, the Polish dissident leader, entitled the Solidarity portion of his autobiography.

I remember when several years ago in Sofia Stefan Tafrov, the Bulgarian diplomat, told me excitedly that, when he travelled to Poland for vacation in August 1980 (rather against the touristic current), he felt something special in the air when he crossed the border. Because of the information embargo, he could not have known anything about Solidarity at the time. Later this atmosphere drew him in to the extent that he learned Polish, as did many foreign intellectuals who came into contact with Poland during Solidarity. Polish became the “language of freedom”, as Adam Michnik put it.

What changes most during a revolution such as Poland’s Solidarity or Ukraine’s Euromaidan is interpersonal relations. Everyday human egotism is replaced by altruism, cynicism gives way before universal nobleness, rivalries are replaced by cooperation and self-help. People are never as well organized as they are during a revolution – anyone who saw the kitchens at Euromaidan knows what this means. We do not know whether the invisible hand of revolution would overpower the invisible hand of the market. So far it has handled the fists of Yanukovich and Berkut.

At the realized utopia of the Maidan, the private became public. Provisioning, sleep, healthcare, security. You walked through the Maidan and you are presented with food, clothing, a place to sleep, and medical care. Even the services of a massage therapist or a psychologist. At the Euromaidan, everything was shared. Even if the taste of coffee or “everything soup” had their own revolutionary character, they tasted exceptional, as exceptional as the event itself was. At the Euromaidan everything was held in common.

Mychailo Wynnyckyj, 19 February 2014, written in English

[Note: this text was written one day before Ukrainian authorities organized the sniper massacre.]

I spent a few hours on the Maidan today. Honestly – I couldn’t find a single terrorist! I saw lots of young and middle aged, determined people who were genuinely trying to show brave faces but are in reality fully cognizant of the futility of their fight against several thousand armed interior ministry fighters and Berkut special troops.

Morale on Maidan is kept up by the many thousands of local Kyiv residents who have showered the protesters with support (food, medicine, clothing), and by the newly arrived demonstrators from the western regions (those who were able to get through before the roads and rail lines into Kyiv were closed).

The fact that fires continue to burn on the perimeter of the protests tonight is testament to the fact that Maidan has massive support from the Kyiv population: this afternoon, every street in the city centre was filled with locals walking to Maidan with food, tires and firewood. While I was on the Maidan, I heard the announcement: “please don’t bring any more sausages; we have more meat than we can eat!”

Based on what I saw today, if anyone is to be called a terrorist, it is not the protesters, but rather the Berkut snipers they face. Let me describe the scene I encountered at about 5:30pm. During a brief interlude in the fighting, one of the front line demonstrators ventured into the ash and debris covered no-man’s land – a strip separating the line of protesters from the line of riot police approximately ten to twenty meters wide. He was searching for firewood and tires that could be added to his barricade fire; he did not approach the police line; he was not at all aggressive. Suddenly, a riot police officer emerged from behind the Independence Monument (the “stella”) with his pump-action shot gun. He fired, and the young man who had been carrying tires in no-man’s land fell. Seconds later, three protesters had jumped over the barricades to retrieve their wounded colleague. Medics were called. I can only hope that the bullet was rubber…

This was the first time in my life that I had witnessed a real act of war. I hope never to see another one, but on the other hand, I should confess: getting to Maidan was scarier than actually being there. The twin threats of titushky attacks and of random harassment by police are very real in Kyiv. Being in the middle of a warzone (after last night, Maidan is nothing less) is very real as well, but there is a feeling of righteousness when you’re there. And you feel invincible. Maidan is a simple place: there’s us, and there’s them. We’re good, they’re evil. That means we’ll win, and they’ll lose. Nothing could be simpler and more comforting.

Yaroslav Hrytsak, 5 April 2014, written in English

In January I understood that I am not a hero.

From a certain moment, when the demonstrations turned into ongoing protests, and the riot police of Berkut chose to attack the Maidan during the night time, a certain unwritten code of behaviour was established: you have to stay at the Maidan for at least two nights in row.

People like me were shifting from Kyiv to Lviv, especially on the days when the situation looked extremely dangerous. These were very cold days and extremely cold nights, when the temperature fell below minus 20 degrees Celsius. We went to the Maidan taking all the measures and precautions against the frost that we could. We stood there from 8pm, and we were supposed to stay there until the dawn the next day. “Stood” is not the correct term here: you cannot stand on one spot during such a frost. You have to walk constantly, making large circles within the perimeter of Maidan. From time to time, you may try to warm yourself with a cup of hot tea or instant coffee – but if you initially succeeded in this, it would last for a few minutes only.

Kyiv, 19 January 2014. Frozen, burned out vehicles. The first morning after battles between protesters and police on the Hrushevsky Street, near Dynamo Kyiv stadium. Photo: Sergii Morgunov. Source:Shutterstock

On the Maidan, you are a pixel, and pixels always work in groups. Groups were mostly formed spontaneously: you or your friend bumped into somebody you or your friend know; and the person whom you met did not walk alone – he or she would be also accompanied by his or her friends. And thus you start to walk together. One night group made a most unlikely group of “soldiers of fortune”: me, my friend the philosopher and a businessman whom I know. He was accompanied a tiny man with sad eyes (he looked like a sad clown, and I found out that he was indeed a professional clown who organized a charitable group that worked with children who had cancer).

We were walking in circles waiting for opposition leaders to come and to announce a further plan of action. People were suffering from cold, but they were also suffering from lack of any meaningful activity. Many demanded a direct attack on government buildings. The negotiations on that day proved futile, as they were on previous days, and the opposition leaders were very late to announce it. Actually, they were very embarrassed to deliver their message that they had achieved nothing – so they were discussing how to sweeten the bitter pill.

Finally, around midnight, this was 19 December, they showed up on the Maidan scene, and they were booed by the crowd. To save the situation, Arseniy Yatseniuk gave an order: to extend the perimeter of Maidan a hundred meters further, closer to the government buildings, and to build a new barricade there. The order made no sense, and everybody realized this. Still, people followed the order – they understood that there must be some kind of action after all. Very angry and very cold, they formed rows and marched to build this useless barricade. A group that was closer to the scene literally arrested Yatseniuk: they encircled him as he was leaving the scene, and led him, and his fancy cloth and shoes, to build that damned barricade. Journalists put their camera with the lights on him and “his escort”, so I saw clearly his unhappy face as he was passing by.

I did not make it to the barricade. Together with other groups of people, I deserted the Maidan. It was 2am, I was freezing, and illness prevented me from carrying anything heavier than three kilos. Still, I did understand that these were nothing but excuses. This is how I come to understand that I am not a hero.

Still, the awareness of this fact helped me to understand the determination of these people who stayed and built that barricade. There was something of the “existential situation” that was described by French existentialists; Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus came immediately to my mind. I presume that most of those barricade builders had never read Camus – but they acted like him: they were resisting absurdity. And most amazingly, they did so with such strong determination!

So together with awareness of my cowardice, another thought dawned on me: the Maidan is really invincible – you cannot defeat the people like these.

Anton Shekhovtsov, 5 April 2014, written in English

When on 16 January, the Ukrainian parliament adopted a number of so called “dictatorship laws”, it was obvious for me that the Euromaidan protests would dramatically radicalize. I had a very strong feeling that something significant and violent was about to happen, and I was sure that the Right Sector, Euromaidan’s far-right movement, would be involved in this.

This feeling was so intense that I simply could not stay in Sevastopol any longer and took a flight to Kyiv in the morning on 19 January. I caught up with a colleague, who also studies the Ukrainian far Right, and we went to Maidan. We listened to speeches of the opposition leaders, and I felt that the audience was increasingly dissatisfied with what they heard. The “dictatorship laws” changed everything and effectively outlawed the Euromaidan protests, but while the audience demanded more radical action (some held banners saying “No more songs and dances!” – meaning that peaceful protest had failed), the opposition politicians did not change their moderate rhetoric.

The demand for the radicalization of the protests hung thick in the air. We went to the bank where the Right Sector was based – in addition to the fourth floor of the Trade Union Building –, in order to observe their activities. A unit of the Right Sector had just finished its regular exercise of forming a line formation and enjoyed some free time. Most of them wore masks to cover their faces but sometimes removed them to have a cigarette. We were walking among them taking occasional notes. They were obviously waiting for something, so we waited too.

And then I saw a picture that disrupted a certain pattern of my understanding of the Right Sector. I saw an activist who was standing there without a mask; he was hardly over twenty and despite the menacing paramilitary outfit he was far from looking like a soldier. He was quietly talking to a woman, and from the way they communicated I realized that it was his mother. She had come to the Maidan to see off her son who was going to a very real war.

At that point, nobody had been killed while protesting, but a few activists had already been kidnapped and murdered by Yanukovych’s regime. At the same time, it was clear that adoption of the “dictatorship laws” implied that the regime was perfectly ready to start killing the protesters, so the mother’s concern was more than understandable. I was looking at them and thinking of the dozens, if not hundreds, of such personal dramas.

That day finished with the confrontation on the Hrushevsky Street – the confrontation that started the more violent part of the Ukrainian revolution. Obviously, the “riot pornography” picture of burning cars and tires, sounds of grenades and a feeling of suffocation amid the tear gas superseded many a memory of that day. But the image of a mother seeing off her son remains.

William Risch, 18 January 2014, written in English

I met up with Nazar after my visit to the Kherson Region’s tent on the Maidan. He was right around the corner, behind the small wooden buildings in front of the Independence Column (the Stella). He was with a few people who were putting up signs announcing a protest against the dictatorship laws and state terror for Sunday 19 January at 12pm. Nazar and a younger women were passing around bunches of leaflets and giving instructions. I agreed to help them.

I was to distribute leaflets along Kyiv’s metro route. Leaflets against the regime’s laws that had just been passed the previous Thursday. Suddenly, I remembered researching young people in Lviv during the 1960s and 1970s, who handed out leaflets and eventually got into trouble with the KGB. One woman recalled the sense of dread she felt when she agreed to go along with her classmates and spread anti-Soviet literature, yet also the sense of obligation, since she had made a promise to the group.

Here I was, making a promise to Nazar and his friends to spread protest leaflets in city metro stations. I told Nazar that I couldn’t do it alone, and he assured me that we’d be working in groups. So I donned my protest placard, and the woman coordinating events put a Euromaidan ribbon on my coat.

At one point, we got off at a station, Lukianivs’ka, I think, and we began our work. We all stood at the top of the escalator that went down to the platform. Two of us covered the people coming up, two of us covered the people coming down. We were greeted by a woman in her forties or fifties, round, solid, with a very strong voice. She had already been passing out a number of leaflets, leaning on her cane, booming out: “Chytaite pro nashi zakony! Chytaite pro nashi zakony!” (Read about our laws! Read about our laws!)

For a while, it seemed like no one was interested in my leaflets. One, two, then dozens of passers-by ignored me. But then, here and there, people of all ages, women and men, boys and girls, started to take leaflets from me. Some of them wanted more than one.

Some people said, “I know it already!” One young woman in her 20s said, “It’s on the Internet already!” However, we also met criticism and derision, especially from older people. One elderly woman laughed and said as she hobbled by, “You and that Maidan, that Maidan! Give us some peace!”

Then appeared a pudgy young cop from the Metropolitan Police. He came up to Nazar and, in Russian, asked for his documents, then for the permit form he needed to distribute leaflets in the metro. At that point, I thought my career as a dissident was over, and that soon we would be seeing a neighbourhood police station. I started to distribute more and more leaflets. I started joining the woman in calling out, “Read about our laws! Read about our laws!”

By that time, a young man, maybe high school age, maybe a little older, decided to help us out in the other lane. He used the same words. “Read about our laws! Read about our laws!” he called out at full volume, thundering through the tunnel.

In the meantime, Nazar was arguing with the cop, and he was losing his temper. I saw a couple of elderly women go up to the metal fence dividing the two lanes, and, leaning on the fence, berate the cop.

I started to call out even more loudly, “Read about our laws! Read about our laws!” I wanted to get rid of those leaflets. And now people kept taking them, one passer-by after another. Soon I needed more.

I got louder and louder, because the laws, being so ridiculous, were a return to the early 1970s, the days when that young Lviv student feared for her career because she distributed leaflets (and in fact, she was expelled from the university and had to retrain for an entirely new profession, only returning to work as a historian some twenty years later).

And then I added some lines of my own, the new lines being sometimes in Russian, but mostly in Ukrainian. “Chytaite pro novi zakoni v Ukraini! Maibutnie na dvokh storinkakh!” (“Read about Ukraine’s new laws! The future in two pages!”). Once I burst out with, “Chytaite pro novi zakoni Ukrainy, zrobleni idiotamy!” (“Read about the new laws of Ukraine, made by idiots!) I felt a little awkward uttering that one, but it was close to the truth. I got bolder and bolder.

After a while our younger helper had to go. As he got together with some friends on the metro, he wished me success in Russian.

The metro cop came back. I saw him enter my lane. He was on his cell phone. I rushed over to Nazar for help. One of our other activists, a man in his 30s with glasses, also from Lviv, came up to the cop and tried to reason with him. “Sir,” the activist began in Ukrainian. “We have no sirs here,” said the cop. “Okay, tovarysh officer (comrade officer)” the activist replied, beginning a short conversation where he asked for the cop’s name and phone number and entered both in his cell phone. Then the cop went to take away a drunk guy, and we never saw him again.

Later we went our separate ways in the Maidan. I decided to get some dinner at a coffee house near the barricades on Khreshchatyk. The waitress recognized me from last month: “Go ahead and have a seat anywhere!” she said in Russian. “You’re known here.”

I had gotten “involved.” Should I have told Nazar no? I thought back one more time to my days doing research on dissent in Soviet Lviv. I remembered one literary critic trying to explain why such loyal Soviet writers decided to sign a petition protecting a dissident arrested by the KGB in 1965. He said that some people just couldn’t take what the system was doing. They had to say no. They had to speak out, no matter how guarded their protests at the time were.

The laws I read in the leaflet sounded like only idiots could have made them. No country should live under them. What more can I say?

Oleksyi Radyns’kyi, 5 April 2014, written in English

It was 26 January and I was recording video interviews with the rioters at Hrushevsky Street when I saw a man in an old Soviet helmet, carrying an old Soviet-made loudspeaker on his chest.

The scene was full of odd-looking people who had spent many days and nights in the freezing cold, inhaling the smoke from the burning tires, climbing the icy barricades and enduring a lengthy standoff with the riot police, which was every once in a while interrupted by spontaneous clashes. The man with the loudspeaker attracted my attention even among the bizarre crowd. I asked him for a brief interview.

He turned out to be a retired coal miner from the Donbas region who moved to Crimea with his family after his mine was shut down. People from the ostensibly pro-Russian regions of Donbas and Crimea were relatively rare at Maidan. It was clear that his presence at Maidan would make him a kind of a dissident or a pariah in either of his home places.

Like many people from Donbas, he claimed to have known Victor Yanukovych personally when the future president still was a minor Soviet functionary. He said that his acquaintance with Yanukovych made him vote for Victor Yushchenko in the 2004 elections – a highly unlikely choice for a Donbas dweller, where support for Yushchenko was virtually non-existent. Then this man told a story of what happened during the election fraud in 2004.

He went to a polling station and saw the lists of voters, and he discovered that lots of his deceased colleagues from the coalmine were on this list as actual voters (this was a wide-spread election fraud technology dubbed “the dead souls”: deceased people were included into voting lists and later “their” ballots were marked with the “right” candidate). He said he exclaimed: “This is voting from hell, the underworld!”

He claimed that by including the deceased on the voters lists the powers had summoned evil forces from the beyond that had exerted their influence on politics ever since. The task of the people was thus to fight these evil forces and make them go back into underworld.

He may have sounded like a religious freak but he was speaking as a deeply reflective person who was describing his political imagination in a symbolic way. After this conversation the rioters at Hrushevsky Street started to look to me a little bit like the devils from Dante’s Inferno.

I saw this man several times after the fall of Yanukovych. He walked around the Maidan with the protesters who refused to leave the place even after the interim government was installed. Unlike most of the people who stayed at Maidan, he was not simply unwilling to return to his home. He could not. Crimea had been annexed by the Russians.

Ola Hnatiuk, 4 February 2014, written in Polish

In the last week of November I watched in Kyiv as the authorities used titushky [hired thugs] guided by the militia to destabilize the situation on the Maidan. This did not work. On Friday 29 November in the afternoon, as people were leaving their offices, there was a demonstration of strength: the riot policemen of Berkut marched along the Maidan in full gear. A few days earlier they had tried the same thing on Europe Square and it let to clashes (although without victims). Then as now I observed closely the methods of Berkut, their equipment, the way orders were given. I was sure that a struggle was coming, I just did not know when.

Kyiv, 29 November 2013. Riot police divide the Maidan in two. Photo: Ivan Bandura. Source:Flickr

On the night of 29 November came the first act of violence. This was a powerful shock for Kyivans. And with that shock came fear. Nevertheless, from morning to night the next day people came to St. Michael’s Square. Students who escaped the beatings took shelter in the monastery and the cathedral of St. Michael, the patron of Kyiv. They spent the night and the following day there. A demonstration was planned for the Sunday 1 December. But on Saturday it was already clear that people could not wait until the following day. On Sunday at sunrise I called a friend. It turned out that she had already been on St. Michael’s Square for three hours, freezing and unable to make tea.

Organizational matters had been arranged in an effective if simple way. From Saturday night through Sunday morning people came with warm food. That morning I reported for work myself. After about an hour, the woman beside me, much more practical than myself as I could already see, said that she had to leave. After a moment I understood: she was in an advanced state of pregnancy, which I had not noticed thanks to her winter clothes. As though she needed to justify herself, the woman said that she had left a small child at home. This pregnant woman had carried from home about ten litres of hot soup. This episode shows not only the dedication but the courage of ordinary people.

This dedication and courage was more and more evident as time passed. The authorities were constantly trying to exert pressure, to instil fear, to terrorize. And each time they failed. The acts of terror including burning the cars of activists at night and then kidnapping people from the street. Then came the bullets. Using the pretext of a bomb threat, the authorities closed the central metro stations in Kyiv, the ones closest to the Maidan. This was obviously horrible for the inhabitants of a city of five million people, most of whom depend upon public transportation. All of this made Kyivans furious and ever more people came to the demonstrations, including quite a few who had not planned to do so.

At the end of November and the beginning of December people still tried to make jokes. The authorities used the pretext of setting up a Christmas tree to try to clear the Maidan. On the tree people affixed posters and humorous notes, the content of which would not always be appropriate to repeat. But soon no one was paying attention to Christmas trees and jokes. The atmosphere was ever less conducive to humour. People still made jokes, but the jokes were now gloomy.

On the night of 10 December I got an SMS from a female friend. She was on the Maidan and Berkut was attacking. This was very troubling news. Three hours earlier, on my street, twenty meters from my apartment building, I had seen three parked buses full of titushki [hired thugs]. In a flash I understood the plan. Drive people off the Maidan by force, and then hunt them down on the streets. That night it was impossible to order a taxi. My best hope was to stop a car that happened to be passing. But within an hour I found a way to get to the Maidan, thanks to friends and Facebook. I drove together with friends. It was impossible to get close to the Maidan by car, so we walked the last kilometre.

My friends were an invalid who is well over 60, and his wife of about the same age – next to them I seemed rather young, strong and healthy (I am a 53-year-old woman, and of course at my age it is difficult to think of physically overcoming armed men.) My friends are both Jews and I am a Polish citizen, but we all walked together, all of us Ukrainian patriots, convinced that our lives would be of no value if the protests were crushed now. We made it to the Maidan, not without some difficulties. My friend Lena, the doctor, the gentlest being in the world, is only a metre and a half tall – I had to keep her at a distance from the riot police, because I knew that she would tell them exactly what she thought of them and the whole situation.

The next revelations of terror [after the failed attempt to clear the Maidan that night] all had the same goal: to frighten, to humiliate. The authorities did not try to hide what they were doing: on the contrary, they tried to make their actions as open as possible, so that society would see that resistance was pointless. All the while the protestors on the Maidan grew ever more annoyed and frustrated with the powerlessness of the parliamentary opposition. From the very beginning there had been not two sides in the conflict, but three. When on 19 January the three leaders [of the parliamentary opposition] came to the stage and spoke lovely words without any content, people were furious. This was after the introduction of the dictatorship laws, which had banned public gatherings, ended the free press, etc. One of the laws was a ban on wearing helmets [the purpose of which was to make it easier for the Berkut, who tended to beat people in the head]. People on the Maidan now appeared wearing strainers, bowls and buckets on their heads, to show the absurdity of these regulations, and to show that they did not want to live with absurd violence.

Some of the people reacted to the speeches of the leaders the way I did – I went home to warm up a bit, because it was unbelievably cold, to eat something and to be quietly furious. But others understood that the laws of 16 January had made millions of people into criminals. If no reaction came now, then thousands of people would be imprisoned, tens of thousands more would emigrate, and the rest really would then submit. In the next two weeks it became normal for people to walk through the Maidan with masks, helmets and clubs. People began telling a joke that was all too true: a masked man with a helmet on his head and a baseball bat in his hand walks into a café. What kind of a man is he? You can be sure that he speaks three languages, has a higher education and is rather prosperous.

In the main slogan of the Maidan, “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!”, one hears the traditions of the UPA [the wartime Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a nationalist formation whose history has been divisive in independent Ukraine]. Today no one makes that association. The first heroes on the Maidan were the Armenian Serhiy Nigoian and the Belarusian Michas’ Zeleznevsky. Many people on the Maidan, especially those who took part in the patrols of the Automaidan spoke Russian and some considered themselves Russians by nationality. During the protests various opponents tried to equate Ukrainians with anti-Semites, but that had no resonance in Ukraine itself, thanks mainly to the position taken by the leaders of the Jewish community of Kyiv and Ukraine. An artist of Jewish origin spent almost every day on the Maidan, painting its scenes, creating a kind of complete documentation.

The protestors understand that the struggle is an unequal one, that the chances for fundamental change are small. If they go to the Maidan, it is because they do not want to live degraded lives. You cannot fear that they will burn your car or close your business when something much worse is at stake: the return of a system of slavery.

Marieluise Beck, 11 December 2013 to 8 March 2014, in German

11 December 2013: I change out of my grey office suit and my smart shoes, into warm boots, a woollen pullover and a hat. I arrive in Kyiv in the evening. Many media outlets are using without any reflection a sentence that belies their ignorance: “Ukraine wants to join Europe”. However, in fact: Ukraine is Europe!

12 December: The people in Kyiv are already in their fourth week of demonstrating for a democratic and European Ukraine. The Maidan presents a peaceful picture. The citizens wait, the square is well organized. From the provision of food to dealing with the rubbish, the self-organization works admirably. The movement on the Maidan is colourful and has wonderfully sympathetic sides to it, culture and politics stand together. But: there is also a problematic side to the Maidan, that of the rightwing extremists who tear up women’s placards and wish to know nothing of gay people. It is therefore a place suited to provocateurs. I hope that there is enough political wisdom and responsibility to ensure the democratic idea the upper hand.

13 December: Just now a mixture of folk festival and winter blockade on the Maidan. Open University: Every morning from 10am there is a large stage for all lectures. That is what it’s all about: open society. The Maidan is Europe. Nonetheless, one looks to the weekend with concern. Through party, business and community structures, president Yanukovych has orchestrated an Anti-Maidan. Each administrative area is encouraged to recruit 250 demonstrators.

Although the citizens unreservedly refute the use of violence on the Maidan, there is an increasing danger that provocateurs under orders provide the security forces with a pretext for violent intervention. There are 80,000 police posted in the city from throughout the country.

14 December: I make my way to the Anti-Maidan. Only 200 metres away from the huge civic festival, the powers that be have staged an opposition demonstration. One has to make one’s way through a martial cordon in order to make it there, where it’s not at all colourful like the Maidan but rather sad. Here we are confronted with an image and a way of thinking that hails from the former Soviet Union.

It is overwhelmingly men from the “working class” – they fear losing their jobs and want “order and someone to lead”. They certainly want to join Europe but the president “only found out three weeks in advance of signing the treaty what exactly has been negotiated and these people will now be punished”. This is what the opposition demonstration is given to understand. Beyond which, the West has given millions to the demonstrators on the other side. But they find it good that we have come to meet them rather than only meeting “the others”. They don’t want any violence. “For we are all Ukraine.” It is here that one has to negotiate – and communicate. Where is Europe?

15 December: Maidan, 24th day. Here stand without a doubt the people. They want to see an end to corruption and to politicians using their power to get rich. They want good governance and freedom. A banner with the slogan: “Belarus is with you!” Contrary to the motives of the opposing demonstrators they say on the Maidan: “We’re not here for money”.

14 January 2014: Last weekend, Maidan activists from all over Ukraine gathered in Kharkiv. The first step toward a joined up Maidan movement.

19 February: As I arrive in Kyiv, the first dramatic escalation of violence on the part of the security forces against the people on the Maidan has already taken place. In spite of which, new citizens continue to gather on the square.

In addition to young people who appear to be students there are also well-dressed citizens, as well as the self-organized Maidan security forces with their martial appearance. The light-spiritedness of the first weeks has faded and given way to a pronounced sense of determination. Now that victims have been claimed, the protestors don’t want on any account to give up any more ground.

Impressions of tonight: young, thoroughly civil people distribute food. Not with their faces covered, but following the rules of hygiene …do “fascists” look like this, as tweeted by political spooks? Whoever takes on board the shibboleths of the Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov and denounces the Maidan as a product of the radical Right, they stand on the wrong side of history.

20 February: There is no civil war here but a regime without a conscience that’s leading a war against its own people. No one among us anticipated new violence last night, for the three foreign ministers of the Weimar Triangle were ante portas and it was beyond the powers of our imagination to think that Yanukovych would preface talks aimed at compromise with an orgy of violence.

As the citizens try in the early hours to drive the security forces back, the regime is obviously ready to deploy snipers to mow down in a blind rage the civilians in the square.

This prompts me to recall pictures from Hungary in 1956 as well as from Prague in 1968. Of course, there are no Russian tanks now, but the unswerving will of the people to be liberated from Yanukovych’s regime, with its lack of a conscience, is obvious. The people don’t leave the square because there is violence but come there to join the movement.

Courageous doctors and first-aid attendants at Euromaidan. One first-aid attendant implores me to help. It was the same in Bosnia twenty years ago. Priests, crying, bless the dead. Last night it was still peaceful on the Maidan with a young, friendly, open public. But the crowd’s anger increases continuously in view of the many dead. More spilt blood can only be avoided if Yanukovych approaches the opposition.

21 February: I hardly want to sleep. What will tonight bring? If it’s true that Yanukovych has fled for Kharkiv and Russian voices announce that they would fight for Crimea then things will be terrible. The compromise (negotiated together with the ministers of the Weimar Triangle) is no longer credible on the Maidan. After the many dead, it may well have come too late.

22 February: The presidential palace has been taken peacefully. No rioting. The people gape at the wealth. Friede den Hütten – Krieg den Palästen [Peace to the shacks, wage war on the palaces]. Atmosphere like Berlin in1989.

7 March: Back in Kyiv. The situation is very tense. To what extent can the people rely on the “West”, to what extent will Putin be allowed a free hand to “take” Crimea? Will he then feel emboldened to destabilize the eastern part of the country? More questions than answers. Only one thing is clear: Putin forges unity among people with his aggression, regardless of whether those people are Ukrainian or Russian speakers or Jewish. Wir sind das Volk.

Kyiv, 8 March 2014. Women’s Day on the Maidan. Source:Facebook

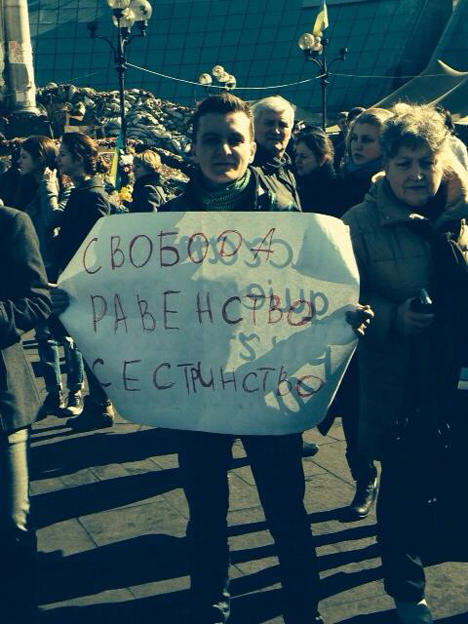

8 March: Women’s Day on the Maidan. A transgender poster: Freedom, equality, sisterhood!

Irina Kalinina, 4 April 2014, written in English

I know that you have asked me precisely because I watched the Maidan from a great distance, both in geographical as well as personal terms. I live and work in Donetsk, the political base of Viktor Yanukovych, and I took no part in politics on either side in these weeks and months. So what I would like to do is share three of the stories of the Maidan, which, for whatever reason, left an impression at such a distance. These are stories that were present in the Ukrainian media, for which the Maidan was a period of renaissance.

1. They saw that I was a reporter, and they shot me anyway.

Natalka Pisnya, a television news reporter, interviewer and red-carpet correspondent, is best known in Ukraine for her reports from the Cannes Film festival and her witty interviews with famous people from all over the world: English actor Hugh Laurie, French singer Patricia Kaas, the Russian politician Irina Khakamada and many others. She’s a single mom and an experienced journalist.

On 20 January Natalka Pisnya was shot in the leg by riot police while reporting from Hrushevsky Street, near the entrance to Dynamo Stadium entrance, where major clashes took place. Medics and activists carried Natalka to a safe place where she was given first aid. One of the activists who had helped Natalka that day was Mykhaylo Havrylyk, a Cossack who was later caught, stripped naked, beaten and brutally tortured by Berkut special forces.

Despite having been shot, Natalka finished her report on that very day. She decided to keep the rubber bullet that had hit her as a reminder for herself and later commented on the incident, saying: “They saw I was a journalist, and they still shot me in the leg. I guess if they’d wanted to shoot me elsewhere, they would have done it.”

2. The Chuck Norris of the Maidan

Oleksiy Mochanov, a famous Ukrainian racing driver, automobile journalist and test pilot, was one of the Maidan activists. On 22 February, he took the stage during the Viche and in his charismatic manner spoke about things that were on his mind: corruption, Ukrainians who have long outgrown their weak-willed politicians, his hopes for the new Ukraine…

When commenting on the Automaidan, groups of usually prosperous car owners who follow politicians and help with organization, he said: “With all my respect to the Automaidan guys, I do not stick with them. I always work alone. Just like Chuck Norris. The fewer people you know, the less of them you’ll turn in when you get caught, which is important.” Since then Oleksiy is known as the Chuck Norris of the Maidan. Although Ukrainian protesters had gone through some horrible times, they still managed to keep their sense of humour.

3. A daughter whose father was killed during protests

Olena Shvets, the daughter of Viktor Shvets, the 63-year-old Ukrainian man who was killed by a sniper during protests at the Maidan, spoke about her father on Ukrainian television. According to Olena, Viktor was a very loving father and grandfather. Olena spoke of her father in the present tense:

“My dad is a retired submarine officer, and a Master of Sports of the Former Soviet Union. He is not a member of any political party, not even an activist. He and Mom occasionally helped people of the Maidan by bringing food and warm clothes. On 18 February they were watching television non-stop. On that day he told my mom that he couldn’t just sit at home and do nothing about young guys being shot at the Maidan. So he decided to go there.”

Viktor never came back.

Kyiv, 13 June 2014. After the Maidan. Institutskaya Street, where the “Heaven’s Hundred” lost their lives, 18-20 February 2014. Photo: frescomovie. Source: Shutterstock

Published 27 June 2014

Original in English

Translated by

Marysia Blackwood, Tatiana Zhurzhenko, Timothy Snyder

First published by Eurozine

© Timothy Snyder / Tatiana Zhurzhenko / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- Not epistemic enough to be discussed

- Another lost generation of art?

- A trace of Russia at the heart of Austria

- What makes a humanist kill?

- Something happens, somewhere

- Vertical occupation

- No longer a footnote

- The Ides of March

- Counteroffensive exhibitions

- No peace without freedom, no justice without law

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

From Bosnia to Afghanistan, the neoliberal peace-building model has compounded conflicts and inequalities by eroding the core function of states. But in Ukraine, the co-optation of the recovery process by private economic interests is being taken to a whole new level.

Artist Marharyta Polovinko’s creativity persisted in a tormented form through her experiences as a soldier on the Ukrainian frontline. The words of a recently called-up fellow creative and young family man provide a stark reminder that the Ukrainian military is buying Europeans time.