The neo-Thatcherism embodied but by no means exhausted by the unfortunate Liz Truss differs from the original in its failure to appreciate that the deregulation of the labour markets can only be realized by strengthening the state, writes Bill Schwarz in his editorial to the new issue of Soundings. ‘Thatcherism Mark II is an improvised phenomenon’ that ‘is unsure how on earth the United Kingdom post-Brexit can ever dissemble at introducing anything approximating to a working economy, beyond the primal dedication to slash both taxes and public expenditure.’

The ‘buccaneering fantasies’ of Brexit have been badly let down, leaving culture as the soft target for Conservative intervention. ‘Soundbites come easily; emotions are easily charged; and practicalities aren’t exactly the issue. The culture wars provide an inviting prospect, not least because on every occasion, it seems, Labour is wrong-footed.’

What’s at stake in the culture wars?

New Left elders Janet Newman and John Clarke argue that a restrictive view on parts of the Left as to what constitutes ‘real’ politics tends to ignore the Left’s roots in cooperative, mutual and internationalist forms of politics, marginalizing a diverse array of social movements and their struggles for rights and redistribution.

‘The refusal to take culture wars seriously reflects a combination of left-wing orientations that connect Marxist scepticism about “superstructural froth” … to Labourist desires to reconstruct fractured relationships with ‘traditional’ working-class Labour voters,’ comments Clarke.

Newman concurs: ‘Resistance towards what might be called a progressive cultural politics reflects a longstanding scepticism on the left about culture, social movements and what are usually dismissed as “identity politics”. That dismissal masks the complex histories of the movements that struggled for material, as well as cultural, change. Feminism transformed the cultural landscape of Britain, through dress, language and the symbolic repertoire of protest, marches, camps and collective practices. We introduced new political discourses and representations, making visible the contested boundaries of public and private life, introducing discourses of embodiment and affect, and offering alternate political terrains of engagement. But we were not just concerned with a politics of representation: we also fundamentally challenged the practices of the police, courts, health services, schools, libraries and the media. Alongside other social movements, we brought about substantial institutional, legal and material shifts, many of which, of course, are now under attack.’

The BBC and culture wars

That the BBC is in thrall to the ‘woke’ is a rightwing commonplace and the latest form of pressure placed by conservatives on the BBC. Yet a bastion of the Left it is not, says Debs Grayson in discussion with Tom Mills and Justin Schlosberg in a wide-ranging discussion on how to reform the UK’s PSB.

‘There is a problem with the demographics of people that work at the BBC, and it’s that they are liberals, and are very invested in a particular structure of power that we have, and they are not able to think critically.’ All the big issues – Brexit, Covid, trans issues, anti-vaxxers, the war in Ukraine, strikes, the monarchy and antisemitism – are discussed within a range of positions circumscribed by The Guardian and The Daily Mail. This omits the possibility for genuine dialogue between positions outside the norm.

Are the culture wars a way to preserve that status quo? Schlosberg thinks so. ‘What’s happened with the explosion of digital forms of communication and social media is that the basic ideas about truth that were underpinning the liberal consensus have been exposed – or are subject to increasing exposure. From the perspective of hegemonic power, the best alternative to a relatively cohesive manufactured consensus is complete dissensus – because the alternative is an organic consensus, which could actually be the engine of real and lasting social change.’

What does that mean for the reform of the BBC? According to Schlosberg: ‘You have to find a way to articulate an idea of a truly independent BBC that speaks to public service values, and is going to engage not just people of the left, but also people of the right, including people on the right who have legitimate concerns and critiques – not of the BBC having a general left bias, which we know is nonsense, but genuine and legitimate concerns – as for example, with the whole sovereignty dimension of the Brexit debate.’

Understanding the far right’s online powerbase

Millions of people are consuming, repeating and disseminating far-right ‘culture war’ material online, but if you do not seek out that content and are not served it by algorithms, you may never know it was there. Alan Finlayson Annie Kelly Ben Little Rob Topinka discuss the digital culture wars.

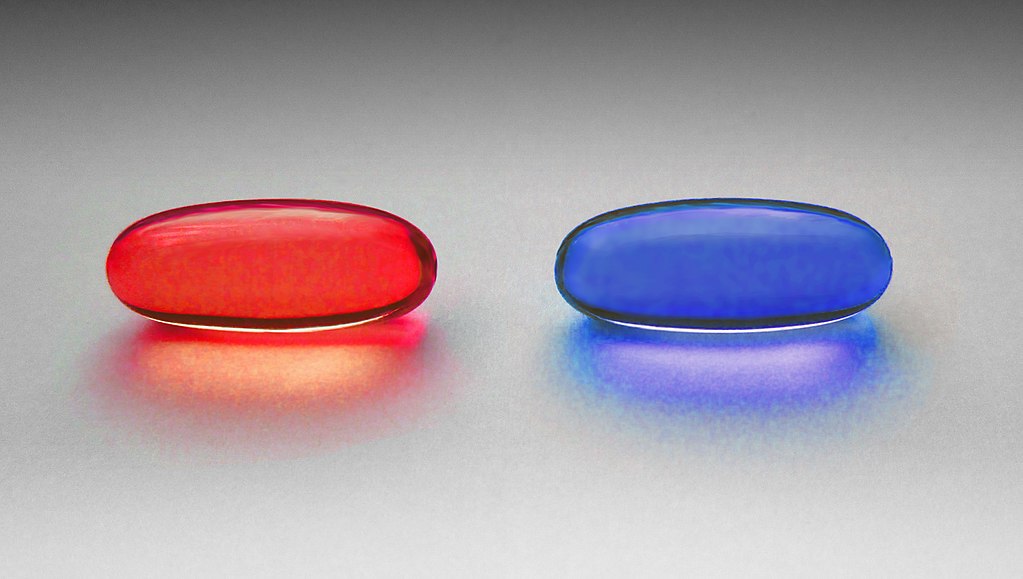

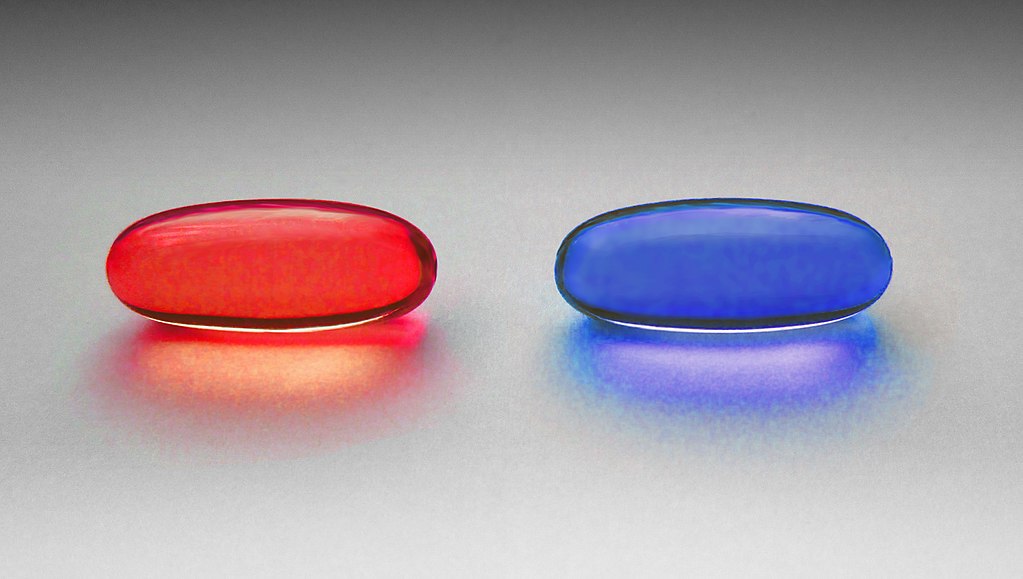

Photo by W.carter via Wikimedia Commons.