Neganthropology

Czas Kultury 2/2024

The politics and psychology of locality: on reviving local communities as high-tech expands and diversifies; forming networks against entropy; the Tortoise Strategy for caring; and rewriting life scripts.

Polish journalists, micromanaged by the authorities, tread a fine line between boondoggling and ritually sensationalizing political debate. The following fragment from ‘Bullshit Journalism: Why is it so bad to work in the Polish media?’ gives voice to professionals under duress.

‘You want content verifiers working with us? The media represent the biggest bunch of hypocrites you can imagine. Journalists don’t need fact checking, they need moral backbone!’ Iwona’s critique may be strong, but it isn’t spurious; she used to work for a major media company, known for its critical stance towards the Law and Justice Party (PiS) that was nevertheless happy to accept revenue from businesses linked to Orlen, the Polish oil and gas company.

Wasn’t this kind of dependence always the case, I hear you ask? Was there ever such a thing as fully independent journalism?

Certainly, in a country as polarized as Poland, press freedom will never be easy to achieve. If a journalist writes about corruption in the PiS, she is automatically perceived as a supporter of Donald Tusk and the Civic Platform Party (PO). Likewise, every word of criticism against the PO is seen as evidence of collusion with Jarosław Kaczyński’s right wingers and the PiS. There is no third way – which is why bold conversations about journalistic freedom recorded in this book are greeted with peals of laughter. Because it’s political patrons who wield the whip, alongside the advertising sector that often has ties with state-owned companies or else with business ventures linked to the opposition. Party political colours are obviously key, until pay rates come into play. The state sector usually offers more money.

Sociologist Jarosław Flis in a lecture about the state of the Polish media suggested that the country’s journalism reflects the dualism of the political scene. According to Flis, it is showy and reminiscent of American-style wrestling: it may look more dangerous than it really is, but, very occasionally, a contestant gets killed.

So, what role can journalism play in all this? Should it report exclusively on political struggles? Could it unmask the artificiality of the game? Or should it side with a single group, presenting it as the ‘good’ option while relentlessly painting the opposition as an embodiment of wickedness? On the whole, journalists opt for the latter. Over the past two decades in particular, this choice has created a new divide between pro-left and pro-right reporting – or rather vying for the right and centre-right: the PiS and the PO.

In Flis’ view, ideological differences in the classical sense were once evident in differing attitudes to the individual and the community. The left – or progressively minded groups – believed in communality where economic issues were concerned, and individualism in the field of social and cultural mores. The right – conservative thinkers – pinned their faith on the opposite. Today, however, mainstream battles are fought between supporters of greater economic and social freedoms, and their adversaries who support socio-economic communality (in ways often bound up with the traditions and conventions of Polish rural culture).

So, in one corner you get those who are well educated, relatively well off and independent, while in the other you see the less privileged – people who are not keeping up with new developments and need economic support from the state.

Clearly, what we are seeing here is class tension. But how does this affect the state of the media, you might ask. In Poland, the overwhelming majority of media outlets and advertising companies represent parties linked to the ‘upper echelons’ of the social ladder, where there is a marked desire for greater freedom and less communality in all areas. These parties have difficulty with less privileged groups and those stuck at the bottom of the pile, whom they view as pitiably ignorant. They communicate a mindset that necessarily brings populists to the fore and this, in turn, leads to authoritarianism and repression. (Yes, I am thinking of the PiS which likes to exploit the sense of grievance in the ‘lower strata’ of Polish society and the growing desire of the underprivileged to get even).

In this scenario, there is little room for social sensitivity or for understanding the perspectives and problems of people with low cultural and economic capital. This includes a growing precariat within the journalistic profession, which generally has just the first group of resources mentioned here at its disposal. What’s more, a nuanced position is difficult to maintain. It would not be true to say that the story about threats presented by one side or the other are entirely without foundation, but tweaking the narrative is problematic because it tends towards the conclusion that, depending on who has the power and the strongest voice, either democracy or the country itself will collapse. In outlining the discourse arising from this thinking, Flis makes metaphorical use of a domestic image: eggs. Some end up hard-boiled, others soft-boiled.

As the media narrative would have it, however, the eggs involved in the social struggle for dominance are exclusively either overdone or raw – which is very far from the case. Some journalists and publicists do detect shades of grey within this black and white palette, making a media story that has been simplified in the extreme look a little more multifaceted.

And what do the authorities do in response? They put those who complicate things out with the rubbish. They discard them into black bags, together with ‘all those pesky symmetrists’1 and ‘crypto-enthusiasts’ from whichever political camp is in opposition (these people are often dubbed the ‘useful idiots’ of both the PiS and the PO), alongside ‘all those’ fundamentalists of the far right, ‘those’ neo-liberals and ‘those’ leftists. As a social commentator, Professor Flis made various attempts to nuance the discussion, but he soon found himself reading out the likes of the following: ‘You say you’re sitting on the barricades but, more often than not, you’re just pissing on us.’

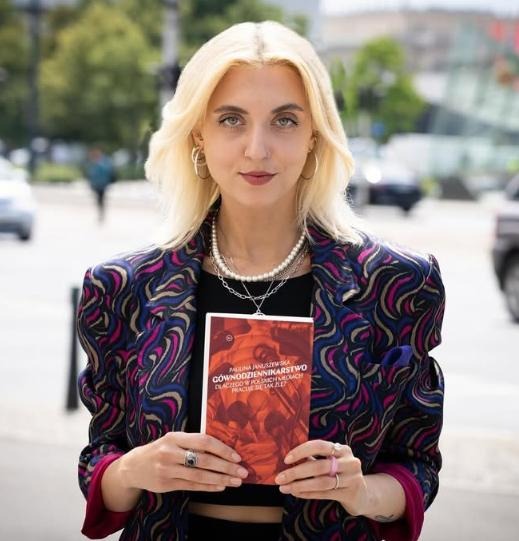

Paulina Januszewska, author of ‘Gównodziennikarstwo’ (Bullshit Journalism), 2024. Image via Instagram

Nonetheless, media employees are no fools. They know someone will always be treading on their heels – or rather not ‘someone’ but specific politicians and business people. And indeed, media organizations are not short of voices prepared to expose ugly cases of patronage and dependence. At times, the way they do so may seem downright brutal, but some journalists risk their careers doing it. Others merely take advantage of the privilege and status they have worked for years to acquire.

Dariusz Rosiak is a distinguished journalist and broadcaster. He is the author of A Report on the State of the World, broadcast on Polish Radio Three and later, with the support of listeners, on the Patronite website. Commenting on journalistic independence, he writes that the profession has always depended on ‘resisting the temptation to succumb to pressure from those who are stronger, more influential and more numerous’ and on not giving way to ‘three kinds of pressure: political, commercial and environmental-cum-emotional’. Let me focus here on the political.

Magda swapped her full-time post in public media for a low-grade, rubbish job in tabloid journalism. She says that in all issues related to economics and employment rights, as well as politics, things look much the same no matter which side you work on. She had imagined that working for an organization, which forms part of the government’s propaganda machine, was about as low as it gets. Then the Internet portals came knocking from lower down.

‘I moved from a big news agency that thought it was running the country, because it supported the government, to a tabloid founded by a guy who worshipped Donald Tusk,’ she tells me. ‘It’s hard to say which of the two was worse. In my old job I was all but branded a half-wit. In the new one, I was exposed to ritual mobbing. Now I’m out of work and very down. I’m told there’s a crisis in mainstream media and journalists are being sacked en masse, department by department. Can it get any worse, I ask myself? Perhaps it can, because I still keep hoping that I might find a way of making a career in the profession. Honestly, I’m mortified to be telling you this.’ I ask her about journalistic objectivity and she taps her forehead in response.

Let’s drop the questions of whether a journalist should hold or express her own views and who is partisan and who isn’t – particularly given that well-known media personalities invite politicians to their birthday parties, or brag on X about sharing bottles of vodka with them. Instead, let’s see how political convictions and sympathies can affect the running of an editorial office.

‘I had two Warsaw-based beats to begin with: waste management and the zoo,’ Magda says. ‘A fucking dream job, no less. But how long can you blather on about lions and garbage disposal? In my case it was about 18 months. Generally, I was just boondoggling – but it was still tiring because I wanted to write and there’s not much I hate more than doing nothing or feeling like I’m wasting my time and letting myself down intellectually. Then I was told I was shirking and didn’t know anything, and that my job was to show that I was toeing the official political line. My boss instructed me to keep making calls to the Ministry of Infrastructure, and to the transport department, to find out in what the President of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, was getting wrong.’

On another occasion she was sent out to Grochów, a district of Warsaw, to look for ‘green waste’ such as backlogs of uncollected fallen leaves. This time it was the locals who were baffled when Magda asked them about Trzaskowski’s supposed negligence. Once she even left work early to check what people in Grochów were putting in their bins. ‘I know how it must sound, but I was desperate,’ she admits ruefully. ‘I thought I was missing something. I really believed those uncollected leaves must be there.’

It is getting towards evening and we order a couple of coffees because we hadn’t got anywhere near the end of Magda’s professional peregrinations. We hang around in the bar until staff come in to clean the floor. Then we stand talking outside the entrance to the Metro, though the weather was quite as vile as the propaganda Magda was instructed to drum up. I am offering these details because, according to one school of journalistic writing, a genre scene adds quality and flavour to your text. So here it is: the coffee was black. OK, so maybe there was a bit of oat milk with it. Not soya though.

Magda’s memories of the pandemic are grim. The editorial office treated news about the level of COVID-19 transmission as a conspiracy, and consequently jeopardized the health and safety of its journalists. The deputy editor-in-chief of the state news agency, who came close to giving Marta a nervous breakdown, remained a COVID-sceptic for months after the Wuhan virus took hold. ‘He was anti-vax as well,’ Magda says. ‘He maintained that the pandemic was a fabricated story. It took thousands of news reports for him to twig and see that he was wrong. Meanwhile, during the worst wave of infections, he had an issue with staff working from home. “The editorial office ceases to exist if people are working remotely. There’s simply no point to it,” he used to say – even though you could rattle off your dispatches just as well in the loo. But no, it’s all about the essential nature of the work. What bloody essential nature? Spreading muck, busting one another’s balls and doing the government a favour? There was an office in-joke about the PiS politician and adviser Radosław Fogiel: we called him our ‘Nowogrodzka Street correspondent’ because we had a hotline to the PiS office there.

‘When I did an interview with the security experts who exposed the Pegasus spyware affair, my material was trashed,’ Magda adds. ‘It represented an attack on the government and we only ever published paeans about the authorities. That way the till came out looking clean – though sometimes even the PiS office in Nowogrodzka Street shat on our bosses, after which they’d shit on us, and so it went on. Sometimes, of course, the bosses would pick up some nice, enthusiastic pro-government arse-licker and take him under their wing. But, generally, we were all drowning in bullshit. So I left. And after a while I ended up with a copy-paste website. In the first job I was letting Trzaskowski have it: in the second, my task was to go for “Kaczor” (Jarosław Kaczyński).’

Magda recalls her early days at the online tabloid as a time when she was under close scrutiny and constantly tested by the management checking out who they were working with. Yet the training on offer was minimal. Employees of other Internet portals confirm the same. They say that on-the-job training is usually confined to instruction on how the portal deals with content. It does not cover career development or the improvement of journalistic skills.

‘Why on earth would you need those?’ Marta asks, ironically. ‘It was like leaving a child alone in the woods with a knife: “Let’s see how he manages. Will he find himself? Will he pick up the vibe?” Those guys were just overflowing with their own sense of how cool and awesome they were. The vibe was really just a combination of autofellatio and doing the PO a favour. They thought they were forming an elite to counter those pitiful little pricks from the PiS. They stood one another lunches, they relished their sushi, it was as though they were still back in 2002. They’d watch TVN together and make comments like: “God, Kaczynski’s a clown – but isn’t Tusk brilliant!” So, you see, the propaganda was inverted. It was the opposition, the PO politicians who had their own blogs and were exposing attitudes that were outdated and condescending. Makes me feel sick to remember it. They imagined themselves as Poland’s saviours, defending us all from the PiS ruling class. It felt a bit like the cover of Newsweek, with Tusk on a white charger. They’d publish descriptions of Roman Giertych’s achievements as leader of the opposition. They’d share his “fantastic” tweets about defending democracy, even though his stuff smacked of crassness, reactionary rural conservatism and smut. But as far as my editors were concerned they were “strong words”, “clever comebacks” and “spot on”. And so what if Giertych used to be a cranky, right-wing Catholic fundamentalist? “He had converted, after all.”’

Igor is a former employee of online Polish Radio. He says that the experts invited to give interviews on the abortion issue all came either from the Catholic University of Lublin (KUL) or that ultra-conservative think tank, the Ordo Iuris Institute for Legal Culture. At least no one could complain that they were ‘religious fundamentalists paid by the Kremlin’.

‘Everyone knew what they would say and what this was all about,’ Igor tells me. ‘The public media has worked out ways of countering any attack on the government. If anybody remarked that the PiS had violated the compromise on abortion, they’d bring out Joanna Lichocka to argue that the left had started the row and that the issue was a complete red herring, even though the opposite was true. This is something the government and the PiS both do. During the 2020-2021 Women’s Strike, we were told to write that “these women, who are doubtless sponsored by somebody” were spreading COVID. We exaggerated incidents like graffiti on the walls of churches, which Polish Radio inflated into a major calamity. I used to go along to demonstrations and never saw any aggression from protesters. But then I’d have to go back to work and write that I’d witnessed “scenes worthy of Dante”.’

A woman who worked for an Internet portal affiliated to a national weekly was tasked with telephoning members of the European parliament linked to the PiS, pretending to be a journalist from the BBC. The intention was simply to check if the MEPs could speak English.

Paula was instructed to put together a piece about junk contracts. ‘I had to write a suitably outraged article about how people were working their butts off during the pandemic. By the way, did I mention that I had no formal employment contract myself at the time?’ she queries rhetorically.

Igor, mentioned above, was also employed on a junk contract by Polish Radio and got an assignment to write about how failures in the management of contractual formalities were affecting journalists working on the national daily Gazeta Wyborcza.

Daria, who has worked in the media for 30 years, says that while she was at TVP Info things were very similar. ‘They don’t give you an employment contract. Instead, you get “tasks” from people often dubbed “racketeers”. These are permanent employees who engage in small-time business activities. They may be editors or cameramen who take an advance from TVP and then pick up teams of people to work for them on junk contracts and pay them a pittance. It’s an arrangement that ensures Polish television keeps its hands clean so it can say that, unlike other opposition media, it respects its employees and upholds its values. What values are we talking about here, exactly? Finding loopholes in the law? Misleading the public?’

Mateusz has worked for some of the biggest tabloids in Poland and jokes that, today, journalism ‘is the most useless profession ever’. When he left the daily Fakt to join a competing paper, he was offered neither a contract nor insurance. It happened during COVID, so he quaked every time someone next to him sneezed. Even though most of the editorial team were working from home, and the paper kept publishing calls for everyone to respect social distancing, his new employer insisted he came into the office.

‘The buses were almost completely empty, I remember,’ Mateusz says. ‘You could count the passengers on the fingers of one hand, and I’d be looking at them all nervously, not to say with loathing, in case anyone was carrying the virus. But that wasn’t the worst thing. My employer always kept in with virtually every political party on the scene, but especially with whichever party was in power. It seemed to me that, since I was in the media, it might be worth investigating if the authorities were keeping their hands clean – whether it was the PiS today, the PO tomorrow or the Polish People’s Party (PSL) next week. Because that’s the way it goes in this game. But my line manager rejected virtually everything I suggested. Forbidden topics included the strike at the Polish airline LOT, for instance, or fraud within state-owned companies. The fact that representatives of the opposition were regularly given an official voice in the paper was irrelevant. I was hitting my head against a brick wall.’

So, what really is going on in anti-government media, you may well ask? Can’t you trust them either? Economist Łukasz Komuda doesn’t offer much in the way of good news. ‘Some journalists remain obsessed with defending the so-called free media in Poland – and rightly if naively so. But despite what idealists and ideologues say, ideas and principles are no more than a bit of gold foil wrapped around a mechanism that monetizes absolutely everything. If you can achieve press freedom by battling with an oppressive state – great! But the content that will suit visual advertising, or campaigns led by media agencies, is bound to be very different.’ All this has eroded checks and balances, as well as the ethical dimension in journalism, Komuda says.

A lack of journalistic self-regulation in all areas, not just political coverage, is also highlighted by media specialist Dr Jacek Wasilewski. ‘A fashion journalist is dependent on advertising within the industry. He simply won’t want to write about how climate change is affecting the fashion world while discussing new trends on the catwalks. The critical approach that used to form part of journalism’s professional ethos has been outsourced. It is now the domain of political and social activists.’

Nina, a former journalist with feminist objectives, illustrates Wasilewski’s observation with another example. ‘I used to work with a woman who had an interest in ecology and kept to a firmly anti-capitalist position in everything she did. She put together some excellent critical material about the online shopping platform Shein, and then found out that the advertising department had signed a cooperation agreement with them. Vogue doesn’t even hide the fact that it takes money from Shein, even though the company exploits people and poisons the environment on a massive scale. The Vogue journalist who promoted the retailer is well known and respected in the profession but remains happy for her byline to appear beside a paean to the Shein brand. We may write reports about Ukraine, but suddenly we discover that our media corporation advertises companies that are financing the Russian military. When I hear senior editors complain that journalism was once different, I have to suppress a laugh because – after all – they were responsible for creating the media we have today.’

‘Do you think there’s any kind of remedy for all this?’ I ask. ‘I don’t know. I can’t see a way back,’ Nina replies. The financial resources simply aren’t there. The cash is for the management and the advertisers. It’s for grubby businesses that don’t interfere with the status quo and for sponsored articles that are politically comfortable – not for genuine reportage or investigative journalism.’ She escaped a news outlet in favour of a niche cultural portal and doesn’t hide her amusement at the way things turned out – even though she admits that she’s laughing through tears and that the current set up suits a lot of people. Those who are committed to the ideas and principles they hold are a minority who make conformists feel uncomfortable, she says.

‘In practice, that’s the way it is everywhere. If company X puts down the money but has suspect links with China, you simply avoid mentioning it when you interview their representative or write about their products and technical know-how,’ a journalist with an interest in technology tells me. In politics it’s the same.

Today, the media fall easily into three separate groups, depending on how they are funded. But you cannot ignore the common denominator: the systemic exploitation or self-exploitation in various guises imposed on employees, both women and men. The outcomes that are hoped for vary. They include the dissemination of government propaganda through state media, generating sales in commercial media and the implementation of socially significant ideas, as well as filling gaps created by the state and by private enterprise in their dealings with NGOs. As a result, journalism ceases to be a socially useful activity. It no longer inspires confidence in its audiences, listeners or readers, nor does it seriously engage its professionals.

On the one hand, we are dealing with the defence of mass media which are far from free. On the other, we are lured by temptations to re-Polonize them. The second of these impulses does not aim to revive journalism as a tool for news dissemination or the implementation of socio-political checks and balances, but it does highlight one very real issue: most of Poland’s media outlets are owned by companies that are non-Polish.

Commenting on the economy as a whole, Jakub Sawulski mentions two concerns: ‘the owners of companies that put capital into Poland earn interest from doing so. In other words, some of the profit foreign companies make is reinvested here but part of it flows out of the country, in the form of dividends paid to shareholders for example. Further, there is a danger that, if the present model of economic development is maintained, it will be difficult for Poland to break out of its current role as subcontractor. And, on the whole, the subcontractor earns less than the prime contractor he works for.’

Earnings are effective disciplinary tools, certainly, but in newsrooms they also support a vertical power structure and may undermine solidarity, especially existing bonds between rank-and-file employees and middle management. If we believe that journalism really is the Fourth Estate, then clearly Poland’s public media must be depoliticized and commercial media should put greater emphasis on serving the public. But, for many people in the country, this represents no more than a pipe dream.

This article is based on a fragment from the book Bullshit journalism: Why is it so bad to work in the Polish media? originally published by Eurozine partner journal Krytyka Polityczna in June 2024. The translation of this article was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.

A term used in Poland to describe someone who refuses to take sides in a political argument and remains even handed in their analysis.

Published 28 April 2025

Original in Polish

Translated by

Irena Maryniak

First published by Krytyka Polityczna (Polish original); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Krytyka Polityczna © Paulina Januszewska / Krytyka Polityczna / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The politics and psychology of locality: on reviving local communities as high-tech expands and diversifies; forming networks against entropy; the Tortoise Strategy for caring; and rewriting life scripts.

Expectations, standards, and requirements in higher education vary from country to country. In the third episode of the Knowledgeable Youth podcast Ukrainian students embark on the complex subject of tertiary education.