I should like to begin with a poem. It is by the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa and is the first poem in his collection Message (Mensagem), published in 1934 – at a point when fascist movements had prevailed here and there in Europe, and a state based on this model was also emerging in Portugal: the Estado Novo, an authoritarian dictatorship The motto of the cycle was Bellum sine bello, that is, war without war.

Europe is lying propped upon her elbows: / From East to West she lies and stares, / Face framed with billows of romantic hair, / In Greek eyes the memory glows. / The left elbow is set back behind; / The right is at an angle cast. / That one says Italy where it rests, / This one set aside says England, / and holds the hand that supports her face. / Her gaze, like a sphinx, dark and fatal,/ Towards the West, the future of the past. / The face with which she stares is Portugal.

The pointe may sound surprising for readers from other European countries, with other native languages. Portugal, of all places, located on the far southwestern edge of the continent, is meant to furnish the woman’s face. In time-honoured tradition, Europa is depicted here as a mythical figure, as an allegorical woman hailing from Phoenicia, today’s North Africa, a princess kidnapped by Zeus, a defenceless creature: in fact, little more than a beautiful silent body, exposed to the whim of the male gaze.

The chair of the Russian Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, set out a quite different vision of the continent in a statement on the civilians killed in Bucha, shortly after his nation’s invasion of Ukraine. The man had a vision: Russia’s goal was to ‘build an open Eurasia – from Lisbon to Vladivostok’. To European ears, especially those of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, but also Poland, this sounded less like a proposal than a terrible threat.

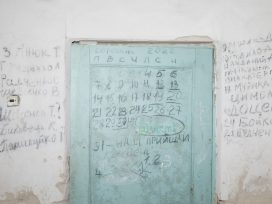

Berlin 1961. Image: Library of Congress / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Now that Europe has rejected the generous offer and resolved to stand by Ukraine in this war of annihilation, it is forced to stand by and see itself criticised as a hotbed of Nazism. Moscow’s new enemy is the European Union, and we should take that seriously both because it serves as a motivation to kill but also because it reveals the real phobia: the Russian problem is not China, not even America. Europe as an association of more or less democratically constituted states is the bastion that needs to be razed, from outside as well as from within, through influence, a war of disinformation, cyberwarfare. Ukraine’s crime was its turn to the West, no more, no less.

Instead, the fantasy of a Europe in the clutches of the current Russian police state. All the more so since, in an unprecedented escalation, its chief of staff threatened the West with nuclear strikes if the European Union persisted too far with its support for the ailing Ukraine. The threat specifically targeted cities such as Berlin, Strasbourg, Paris or Brussels – a declaration of war against the European community or what they over there have since taken to calling the ‘collective West’.

For the first time, I became conscious again of the fragility of Europe, the danger in which this precious continent finds itself. Europe, which is dearer to me (even as the bearer of a German passport) – precisely on account of the catastrophe caused by Germans, supporters of Hitler and his Nazi movement, a world war accompanied by the murder of Jewish people from all over Europe – than the successes or failures of the country whose mother tongue I call my own. In other words, I feel more like a European than a German. I could imagine dying for Europe, I would not go to war for Germany, should that be necessary one day.

Since the beginning of the war waged against Ukraine, I have felt complicit. I often think about the Spanish Civil War, which was the start of the campaign of city bombardments, which then became the norm in the Second World War with the air raids on Warsaw, Coventry, London, Rotterdam, until it was finally visited back on Germany and cities like Hamburg or Dresden were destroyed. Just as Kharkiv and Kyiv are today subject to relentless volleys of missiles. I ask myself what I would have done in the Spanish War, when the International Brigades were being formed. How I would have behaved as a soldier in the German Wehrmacht – what I would have done when the German army marched into Kiev or besieged Leningrad.

I ask myself this and in doing so try to discover where I stand today, eighty years after the end of the Second World War and at a time when the Russian bid to annexe Ukraine rages unabated, a war that for us is hardly more than the daily ritual of disposing of another page from the tear-off calendar. The bystanders who read the newspaper every day to learn how people there are dying, are far away, still protected from the rocket barrages, and have their own opinions. I speak as a European in taking these events – which are and remain monstrous – seriously. Should I pretend that none of this is happening, this daily murder ‘in Ukraine far away’ (to paraphrase a line from Goethe)?

No, not a day goes by that I am not shaken by the attacks, but also by the deaths on both sides of the front. Because war is above all a machine for producing loyalty, on the Russian side for cementing power, for colonizing its own population along with that of Belarus: re-education in the spirit of deadly patriotism. The eyewitness account of an American who was deployed in one of the volunteer battalions fighting for Ukraine: ‘The Russians are using their own people as cannon fodder. They are shooting prisoners of war. These people will not hesitate to eat up their own for political reasons.’

A young Russian historian described it as one of the most senseless wars at the very start. An expression of helplessness, since we know that this ‘special operation’ is part of a calculation by the ruling caste as to how they can hold on to power by the utmost means – and for life. And we are not talking about President Zelensky. The difference is free elections, which have not existed in Russia for a long time. To be clear: this is no longer a conflict between systems as in the days of the Cold War, but one about forms of rule. It is about an imperialist claim to foreign territory, which even a ceasefire would not change – apart from a return to business as usual, America’s, in the form of President Trump’s chief concern, in the name of economic spheres of interest.

Everything that presents itself by way of explanation (geostrategic rationale), or historical background (the collapse of the Soviet Union, the legend of Russia’s isolation, plus all the myths of a third Rome, Byzantium, or the fantasies of a strong Eurasia) fails to grasp this fact. At a moment when thousands upon thousands are being sacrificed for a new tsar, my concern is the irrecuperable tragedy of the Ukrainian people, whom the worst fate has befallen: a fate, moreover, that has no end in sight and will traumatize them for generations.

A word about the preconditions of this conflict, which the few Ukrainians and Poles I know, poet friends, have seen on the horizon for a long time. Two dates from the depths of recent German history belong here, and with them I am back to Europe and its present malaise. One is what I would like to call the Curse of Yalta. It befell Germany – this monster that had to be defeated – and its division as the result of the end of the war. But it also affected the Baltic States, which went to rack and ruin under the wheels – or rather the armoured tank tracks – of this decision. I was reading in the work of an Estonian author how Churchill allowed himself to be exploited by Stalin and made far-reaching concessions to him in February 1945 regarding the expansion of the Soviet sphere of influence. The war was over, but at the Potsdam Conference not only the Baltic States, but all of Central Europe was abandoned.

The other date was the Hitler-Stalin-Pact, the meaning of which is still contentious today, also among historians. On the one hand, this had created certain realities that continue to have an effect today. At the time, as the author Jüri Reinvere explains, the western Allies simply gave their blessing to the spoils that fell to Stalin as a result. Half of Europe was thus handed over to a mass murderer. On the other hand, could it not be the case, and I think it is, that on 23 August 1939, two dictatorships sought to close ranks in pursuit of a joint extinction of liberal Europe?

The fact that Hitler’s Germany finally invaded the Soviet Union and that all this had been a long time in the planning is an objection, to be sure. But that two totalitarian states only became allies for strategic reasons remains a myth, told differently on both sides. It does not change the fate of the Jews in all the occupied countries, including the Soviet Union. The murder of the Jews in every single country under German military rule is and remains an open wound as long as we are discussing Europe. That is why the question of antisemitism is so central and must never be forgotten in the commemoration of the wars of yesterday and today. No, we will not escape of the moment of absolute solar eclipse so quickly, and as it turns out, its shadow remains with us today.

It has become colder in Europe, the spaces are closing again, Europe is currently in the process of rearranging itself. It is understandable that Finland and Sweden have now joined NATO, under pressure from the threat from the East, which is at least a ray of hope. Neutrality is not an option in times when human rights are once more being trampled underfoot. Once it was the order of the day to join a fundamentally European transatlantic alliance which was focussed on defence, the only one without an ideology of attack. Finland in particular has learned a lesson from the consequences of the notorious Hitler-Stalin-Pact. It has an important story to tell about its changed position after the armistice of 1944, the only country to be wrested from Stalin’s grasp.

Also, about how it came to be the venue for the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in 1973, which ushered in a thaw between the icebound blocs. The famous Final Act of 1975, which dealt primarily with human rights issues, the most important aspect for those of us trapped behind the Wall – much more so than the re-definition of those false borders which remained ours to challenge. I certainly felt the wind blowing from Helsinki in the last years of SED rule. There was a kind of juridification of the situation; and dissenters, those who wanted to leave the country, could suddenly point to a legal treaty to which the GDR was also a signatory. I remember the pride of the country, which had scarcely been recognized on the international stage before then, to have been in Helsinki. Even if the obligations that had been entered into as part of the Accords hardly had any effect on the population.

And with that: back to the woman, the kidnapped figure of Europa in the poem, who has been the subject from the beginning. The starting position still seems to be the same. On the one side, the western democracies, changing in their formations, rising and falling, as they always have. And on the other side, dinosaur-like counter-projections, forms of rule that tend towards imperialism and the devouring of all resources and the people in their sphere of influence.

In Russia, this is the special case of a regime that is trying to regain its old stature and strength based on its sacrifices in the ‘Great Patriotic War’. Any talk of the threat to Russia from the West is simply a diversionary tactic; in reality, the goal is to curb grassroots democratic movements in Russia itself as well as in neighbouring countries. Putin’s model of a secret service state feels itself threatened, from outside as well as from within, a situation that could perhaps be solved by the psychoanalytic treatment of those involved, but unfortunately Freud never made it as far as Moscow. A state in which all the forces of the left and right are now forcibly welded together into a bloc that excludes any opposition by means of terror and perversion of justice (the murder of Nemtsov, the poisoning of Navalny, the expulsion of the female opposition, Pussy Riot). A state that is now waging war in order to nip any potential drift towards the West in the bud. For this, war is the last resort to force regime change after all other forms of influence have failed. A sign of poverty, a mark of backwardness.

Europe has renounced waging war, therein lies its inner peace, its modernity. And this was reflected not least in the Budapest Memorandum, which even the Russian Federation agreed to when it joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1994. A golden decade of de-escalation – from today’s point of view, the happiest time of my life. For the first time, Europe was no longer simply that woman kidnapped and fought over by all sides, but a continent that had freed itself from its old myths and the cursed ideologies of the twentieth century in order to look forward to a future without wars and without violence. After Russia’s regression into the past, I can only hope for all our sakes that Europe will seize its opportunity for cohesion in a way that has not before been possible and use it for the future.

The article is based on a speech Durs Grünbein delivered at the Helsinki Debate on Europe, 16 May 2025