To have a body

Esprit 3/2025

Esprit revisits the philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty: including Guillaume Le Blanc on ‘incarnation’; Corine Pelluchon on eco-phenomenology; and Judith Revel on Merleau-Ponty, ‘the eternal runner-up’.

The feeling that we are being watched by a wild animal can lead to shock. Suddenly we comprehend how immense the world is, and how overwhelmingly lonely we feel.

The octopus sat on a stone, wrapped in her own arms. An amber eye glistened amid the soft red of her flesh. I swam up closer, she was within arm’s reach. Her eye widened, unveiling a pupil shaped like a straight horizontal line.

I could see her clearly. And she could see me.

What is it about encounters with wild animals that makes them stay with us forever? Aldo Leopold, father of the ecological concept in philosophy, recounted that one look into the eyes of a dying wolf – into its wild, green fire that, when extinguished, would take with it secrets known only to wolves and to the mountains – transformed him from a hunter into a staunch defender of the wilderness.

Jane Goodall said that the most important experience of her life was the moment when David Greybeard, one of the chimpanzees she observed, looked her straight in the eye. She was holding her hand out to him with some fruit, which he took, yet dropped it to the ground. That wasn’t what he wanted. Instead, he lightly squeezed Jane’s hand. ‘In that moment we communicated in a way that seemed to predate words. Perhaps in a way that was used by our common ancestor millions of years ago,’ she recounted on the radio programme ‘To The Best Of Our Knowledge’.

Photographer Bryant Austin recalls floating in the water when he felt a gentle tap on his shoulder. He turned and looked straight into the eye of a female humpback whale. Her fin weighs a tonne and is almost five metres long. And yet she only gently touched him. Her eye was brightly lit; Austin saw a calm awareness in it. He devoted the next five years to photographing whales on a 1:1 scale.

My encounter with the octopus ended with us taking a walk together – she leapt from rock to rock and looked back to see if I was following her. And while this meeting of minds did not decide my life path, it had an effect on my diet and left a trace that I think will stay with me forever. The sight of her eye comes back to me along with the feeling that I have been noticed and recognised – as a creature with consciousness and a will, unpredictable and therefore interesting.

In that split second when we gazed at each other – a round pupil and a rectangular pupil – I was an animal being watched by another animal. Looking at me, she saw the same thing I saw looking at her. A glimpse of alien consciousness hidden in the pupil of an eye.

The eye of an octopus, photographed in Cirkewwa in 2021. By Victor Micallef via Wikimedia Commons.

‘The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary’, wrote John Berger in the late 1970s in his essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’ According to the British art critic, what we have in common with animals is birth, sentience and death. Man and animal are ‘similar, but not identical […]. Just because of this distinctness, however, an animal’s life, never to be confused with a man’s, can be seen to run parallel to his. […] With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.’

I understand the ‘companionship’ of which Berger writes to be the gaze of a being that reveals its individuality, its singularity to us.

The sense that we are being watched by a ‘wild’ animal (wildness is the key point here: a domesticated animal, according to Berger, cannot offer us its own narrative, because it occupies a place in ours), that we have been noticed by it, can be cause for shock. Suddenly we grasp the vastness of the world – the multitude of beings, each enclosed within a skin, each unique and each alone in that uniqueness. We feel an acute loneliness mixed with a sense that we are not as alone as we think.

The heart of a blue whale weighs as much as a Fiat 126p.1

An early Polski Fiat exploring the Norwegian wilderness in 1976. This car was the same size as the heart of a blue whale. Photo from Fortepan / A R

The sounds made by sperm whales are louder than a rocket taking off into space. Humpbacks can travel up to 25,000 kilometres in one year, moving between the tropics and the poles. And Cuvier’s beaked whales can dive to a depth of three kilometres (the human record on a single breath is 214 metres) and spend as much as two hours underwater.

The whale’s giant body is a representation of the world. During its lifetime, it reacts to magnetic storms on the sun and influences the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. When it dies, it becomes a feast for hundreds of species of sea creatures for several decades or even centuries.

Although whales evolved from dog-like land mammals that entered the ocean 50 million years ago, everything about them is epic, beyond human scale. What do we see when we look into the eye of the world’s largest creature?

The book by Australian journalist Rebecca Giggs, ‘Fathoms: The World in the Whale’, has taken me on a journey through time, cultures, and genres. The author writes that ‘a whale’s eye is looking, unexpectedly. Its vigilance seems to resemble ours – thoughtful, inquiring, knowing. […] Making eye contact with a whale runs a deeper taproot into the human psyche than catching the eye of another sort of animal. They don’t want your attention. They’re searching inside you. For what? What is it that migrates with the look passing from whale to human, human to whale?’

Giggs is not interested in the size of a fin whale’s tongue or the reproductive behaviour of sperm whales. Rather, the whale interests her as an icon. What does it mean to kill a whale, to eat a whale, to watch a whale suffer, to hear a whale, to be in a whale, to dream of whales, to stroke a whale to death?

It is an erudite and at times meditative journey into the depths of humanity. Whales are a mirror in which we have been seeing our reflection for thousands of years. For some, they were harbingers of divine tidings, for others, the source of the oil that fuelled the industrial revolution. For most people today, they are the story of the ability for humans to change.

We associate whaling with creaking wooden ship decks and Captain Ahab from Moby Dick. Yet most of the whales did not die in the 19th century, when whalers were after their oil (used as a lubricant and fuel for street lamps), their baleen (used to make umbrellas or corsets and to beat naughty children) and their bone (for buttons and the keys of musical instruments).

We culled the most whales in the 20th century, when advanced technology, finely lubricated with whale fat, made it possible for us to sail faster and further. Large ships, or more like floating factories, appeared in the oceans, on board of which the great carcasses could be processed and their blubber rendered. Whales were no longer impaled by steel harpoons but by explosive charges. It is estimated that from 1900 to 1999, humans killed 3 million whales – more than in all previous centuries combined. During a single century, the blue whale population declined from 300,000 to 2,300 individuals. The global humpback population shrank by 90 percent, and as many as 770,000 sperm whales were killed in the second half of the 20th century alone.

A mother sperm whale gives us the side eye while swimming with her calf, off the coast of Mauritius. A 2012 photo by Gabriel Barathieu via Wikimedia Commons.

Today, when we board a cruise ship hoping with crossed fingers to see a whale, we are going to see a rescued animal. ‘[…] it’s a double marvel,’ Giggs says.

The spectacle of witnessing immense animals, unhindered in their marine habitats, offered hand in glove with a chance to contemplate our own species’ capacity for temperance […]. To spot a whale is to animate a redemption narrative; to reflect on the supposed moral turnabout of our kind. We wonder at our ability to command nature to such decimating ends. We wonder, too, at our capacity for control ourselves.

In the 1960s and 1970s, whales became a symbol of the environmental struggle. Following a series of high-profile oil spills and the first photograph of Earth from space (taken in 1972 by the Apollo 17 crew, it depicted a solitary blue sphere in the vast blackness of space), the green movement began to take off. Whales had capacious symbolic value, embodying the struggle to save endangered species and to reduce pollution, and the fight for the right to clean air. The animal that had previously been seen as the source of blubber to make margarine and soap, now became a symbol of protecting the planet, thanks to a major international effort.

The whale song made a major contribution here. In times of war, it had been treated as noise that disrupted the search for enemy boats. Yet thanks to activists and artists, it was later transformed into proof of the intelligence of a different species. A whale song album, released on vinyl by biologist Roger Payne, sold more than 10 million copies. When a whaling ban was being debated in the US Congress in 1972, in place of boring speeches, activists simply played a recording of a humpback whale singing.

Thanks to the 1986 international ban on commercial whaling, the population of blue whales has increased and is now estimated to number between 10,000 and 25,000 individuals. There are now between 80,000 and 100,000 humpbacks and 300,000 sperm whales. Giggs believes that we saved them in order to save ourselves.

In the whales, Rebecca Giggs finds a story of last-minute remorse and self-transformation. And much more than just that.

Golf balls. Twenty plastic bags. A dozen metres of crab fishing net. Tracksuit bottoms. Pieces of a plastic bucket. Chicken packaging from Ukraine. Birthday party cups. An entire flattened greenhouse. Disposable cigarette lighters.

Our entire world in the single whale.

Our world in whale blubber, half a metre thick. Pesticides that have been long banned yet entered the sea decades ago are deposited in the tissues of cetaceans. They do not harm the animal until it begins to digest the fat – and during long migrations, fat is its only food. Or until it turns the blubber into milk. The mother whale does not understand what killed her calf.

Our world in the changing tones of the whale’s songs, which have to cut through the noise of container ships with engines reaching five storeys in height and weighing 2,300 tonnes.

Our world in the skinny bodies of humpbacks that are suffering from food shortages in the increasingly acidic waters of the ocean.

Our world in beached whales: 337 whales were beached off Chile in 2015, 656 in New Zealand in 2017 (around 200 were rescued), 470 in Tasmania in 2020 (20 were rescued). Some had been poisoned by toxic algae, others stunned by military sonar.

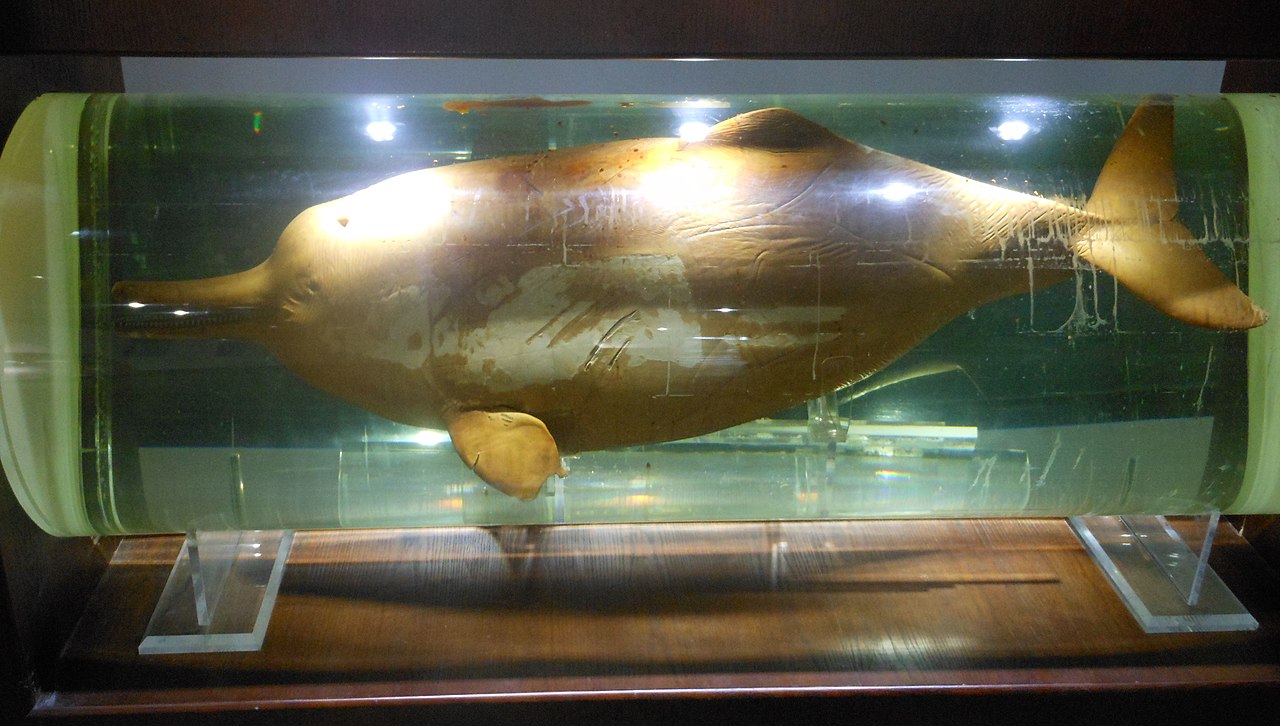

Our world in China’s Yangtze River, where excessive traffic and over-fishing were too much for the baiji, a dolphin species endemic to this river. The last one was seen in 2004. It was declared extinct in 2006.

Sadly, this is the only way to see a Baiji dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) today. This specimen is exibited in a containerat the Museum of Hydrobiological Sciences, Wuhan Institute of Hydrobiology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Photo by Alneth via Wikimedia Commons.

Our world in the fading sounds of the Antarctic BW29. It is a never-seen species – or perhaps a single individual, maybe a hybrid – whose voice has been picked up by the hydrophones of scientists. There are more recordings of other such sounds that do not match any known cetacean species. Some die away before we can discover to whom they belonged.

Giggs looks at the whale and sees what is invisible to us on a daily basis: global warming, toxins, increasing acidification of seawater, noise pollution and plastic pollution. We read about these things in the media, but we are unable to fully register their scale.

Timothy Morton, author of Dark Ecology, calls such phenomena hyperobjects – something impossible to describe because they are so huge, yet things we are heavily entangled in. They are all around us, they are in us, they are us.

It turns out that all it takes is a good look at other species and the invisible begins to take on a shape. Looking at whales helps us to experience and feel, not just understand – the extent of our impact on the Earth.

‘Everywhere animals disappear’ – wrote John Berger in 1977. Although he was concerned with the marginalisation of animals and their perspectives, he could not have foreseen that the sixth extinction was already underway. Animals were disappearing not just from our sight, but from our world. It is estimated that there are 60 percent less wild animals today than in 1970. They now account for only 4 percent of the mammalian biomass – the rest is humans and livestock.

According to the 2019 report of IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services), one million species (yes: species, not individuals) are threatened with extinction. Scientists estimate that there are roughly eight million species in total, most of which are insects. Many of these have yet to be discovered and described. They will be lost before we even find out anything about them.

In recent decades, as much as three quarters of the Earth’s land surface and 66 percent of the seas have been transformed under human influence. We have almost completely destroyed wetlands (85 percent). We have deforested nearly a fifth of the land. And our consumption keeps increasing. Andrew Deutz of the Nature Conservancy calculated in 2021 that we spend more money today on destroying nature than on protecting it.

Many believe that the loss of biodiversity, symbolised by pictures of Chinese people pollinating pear trees with paintbrushes, is an even greater threat to our species than global warming (the two phenomena are closely linked and interdependent). By losing the diversity of life on the planet, we weaken entire ecosystems. A disturbed balance does not just mean fewer ladybirds and frogs. It is a rupture of the networks of dependencies that sustain our existence on Earth.

One such network is formed by whales, phytoplankton and ourselves, among other things. Cetaceans fertilise the upper parts of the ocean so that microscopic plants can grow on the surface of the water, producing more than half of the oxygen present in the air we breathe. A thought we do not like to embrace is the fact that Homo sapiens is just another species of fauna, dependent on others – and thus could also become endangered.

As the philosopher Andrzej Marzec points out in his book ‘Anthropocene. Philosophy and Aesthetics after the End of the World’, ultimately, THEIR extinction is OUR demise.

The speculative exhibition ‘Mitigation of Shock’ prepared by UK-based design studio Superflux was shown in Barcelona in 2017 and Singapore in 2019. Superflux envisions a not-so-distant future: it presents the interior of an apartment in the second half of the 21st century. The view from the window shows flooded streets and high-rise buildings with balconies turned into vegetable gardens. In the kitchen is a jar with a portion of rice for five weeks. Ration cards for sugar and electricity are laid out on the table. On the bookshelf, we have ‘Pets as Protein’, ‘Feast for Free. Foraging in Pulau Ujong’, or ‘How to Cook in a Time of Scarcity’. Pinned over the countertop is a recipe for a roach stir fry. In the corner, we see a small ultraviolet tomato farm and a DIY hydroponic kit made from Ikea boxes with green seedlings. And at the entrance, we have a rack adorned with spears made from hangers and sharp pieces of plastic – repurposed CDs and computer chips.

In the description, the authors invited guests to ‘experience a world where extreme weather conditions, economic uncertainty and a broken global supply chains mean widespread resource scarcity’. I saw the exhibition the week before Covid-19 hit Italy.

Two years later at the Venice Architecture Biennale – held under the motto ‘How will we live together?’ – Superflux presented a table hosting a post-apocalyptic feast. A fox, a pig, a snake, a raven and bees are seated next to a human at a piece of wood salvaged from some cataclysmic event. They feast using mangled cutlery pieced together from fragments of the human era and discuss the new rules of the game.

Are we ready for this? How much more evidence do we need that the world around us, along with our narrative about it, is crumbling to pieces?

When Giggs looked into the eye of a humpback whale, she felt as if the cetacean’s gaze had frozen time. Only moments before, she had watched in horror as the seventeen-metre-long animal glided beneath the catamaran filled with people holding binoculars. One flick of the tail and they would all have been in the water. Giggs understood what it felt like to be the prey. But when this female humpback positioned herself alongside the boat and turned her eye to look straight at the journalist – fear gave way to awe. Today, contact with animals gives us something far more, Giggs says, quoting writer and activist Barbara Ehrenreich who explains it as experiences that ‘people have more commonly sought through meditation, fasting, and prayer…’

So the animal’s gaze is a window into the solitude (and extinction) of a species, a spiritual experience, a symbol, a mirror.

The only thing is that the humpback whale – like other cetaceans – is myopic, at least by our standards. Above the waterline it is probably unable to distinguish much detail. From a distance of several metres, this particular whale would not have been able to see Giggs’ eyes staring into hers, much less freeze time by the sheer power of her gaze.

When we talk about how we observe animals, we are duplicating our own narrative. We see ourselves in them, because we are the ones weaving the story. In the story, each animal – a wolf, chimpanzee, or octopus – can become a mirror, and indeed a spiritual experience and an impetus for self-transformation, if we are willing to look closely enough. But instead of seeing ourselves in them, can we see them for who they are?

After all, the point should not be for animals to serve a narrative about ourselves, even if it does lead to a glorious personal epiphany. Yes, it’s important to see our own destructive power in the eyes of animals. But to me it seems even more important to see the animal itself.

In the 1980s, the eminent writer Ursula Le Guin (1929-2018), gave a lecture that was later published as an essay entitled ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’. The author, a specialist in alternative perspectives, writes about the origins of narrative. In her view, human storytelling originated from boredom – it was used to fill the time around the campfire. But how do you tell a fascinating story about pulling up root vegetables? A chilling tale about chasing a mammoth with a spear promised much more of thrill – it was full of testosterone, risk, death, victory and heroism.

In fact, hunting mammoths was not an absolute necessity. Our ancestors did just fine on a diet of berries, nuts, and grubs, besides the occasional mammoth. But in addition to the meat, the mammoth hunters brought back a story. According to Le Guin, it is this story – linear and adventurous, involving a kill made with a long, simple tool and, above all, with a Hero – that has dominated human culture for several thousand years. And while the story also features other characters, it is not their story.

The author further explains that ‘so long as culture was explained as originating from and elaborating upon the use of long, hard objects for sticking, bashing, and killing, I never thought that I had, or wanted, any particular share in it. […] Wanting to be human too, I sought for evidence that I was; but if that’s what it took, to make a weapon and kill with it, then evidently I was either extremely defective as a human being, or not human at all.’

Le Guin is not interested in the story of the Ascent of Man the Hero. ‘You just go on telling the story of how the mammoth fell on Boob, how Cain fell on Abel, and how the bomb fell on Nagasaki […],’ she quips and leaves the heroes to themselves while goes out to pick berries, nuts and rootlets. She stashes them in a carrier bag, takes them home, shares them with others and makes preserves for the winter. In doing so, she discovers that humankind’s first tool was not a spear at all, and the first story was not the one about thrusting that spear into the heart of a mammoth. The first tool was a container – a rolled-up leaf, a woven basket, a bag. And in this story of the origins of humanity, Le Guin finds herself. ‘If that’s what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully, freely, gladly, for the first time.’

If we were to listen to the berry-gatherer, the story would resemble a bag in which each object has something engaging to recount. As he tells the story, he pulls the objects out in no particular order, with no particular purpose, because the purpose is to be together, to listen, to delight and to gain knowledge.

‘Conferences may have replaced the campfire, but the principle is basically the same: it’s the story, the legend [and the Hero], that matters,’ writes Siobhan Leddy for ‘Outline’, in a comment to Le Guin’s text in 2019.

Two years later, I am observing the international leaders and delegates in October [2021] at the virtual UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, and in November at the face-to-face UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow. Leaving aside the obvious futility of holding the two summits separately, it is clear that what was supposed to be a great success has turned into a game of words and petty politicking.

The representatives of Tuvalu talked in Glasgow about their sinking islands and how in a few decades they might not have land on which to be a nation. Yet when the Polish prime minister spoke about a just transition and ensuring citizens’ security, he was not really thinking of the citizens of that remote archipelago (it isn’t without reason that Poland was given the title of Fossil of the Day in Glasgow by environmental campaigners for holding on to coal-based power).

Activists who demand bolder action are shut out of the negotiations at such summits. Decisions are made too slowly because our world’s dominant narrative is one of economic growth. Nothing will change until we rid ourselves of the cult of the Hero who slashes, stabs and kills. And the linear narrative needs to go down with him as well. Today’s heroism involves making enough room for the stories of others. Perhaps they are not as heroic and engaging, although this may just be a question of habit. Yes, it may be difficult to tell an intriguing and passionate story about gathering roots. But it is not impossible.

A lot of treasures have accumulated in my bag over the last few months. I read about fungi, bacteria, trees, lichens, jellyfish and termites. I have no idea where this sudden fascination for biology comes from, but I’m unable to digest anything else. I prefer the drama of ants, in which a predatory fungus takes control of the brain, to human drama. I find myself reaching for the stories that exist alongside ours, written by people who are specialists in giving up their space for others: Anna Tsing, Ed Yong, Donna Haraway, and thus learning about the web of interconnectedness. No story exists in a void. After all, the mammoth story, in addition to Oob and Boob, features a mammoth. And then there’s the tree from which the spear was carved, and the berries, and the roots that both hunter and prey fed on. And this is only a tiny art of the relationship, the most visible one.

With each species that goes extinct – the Spix’s macaw, the northern white rhino, the Hawaiian snail, the cetacean and the lice that live on it – a narrative in Le Guin’s carrier bag is lost. Along with each of them, we lose a way of life on Earth that had evolved over millions of years. We become poorer, being deprived of yet another narrative about a relationship with our environment.

‘It sometimes seems that that story is approaching its end,’ Le Guin wrote in 1986. ‘Lest there be no more telling of stories at all, some of us […] think we’d better start telling another one, which maybe people can go on with when the old one’s finished. Maybe. The trouble is, we’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story, and so we may get finished along with it.’

This was unnecessary, says Ursula LeGuin. Also, do note how the men facing the viewer wear modesty loincloths, and the rest exhibit their naked behinds. An etching from William Cullen Bryant and Sydney Howard Gay’s A popular history of the United States from 1876 bears an interesting testament to modernity’s view on history and nature. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

For Berger, the history of Homo sapiens is a story of the separation from animals and their perspective.

Animals were once messengers of the divine, whose livers revealed the future to fortune-tellers. At the same time their behaviour shaped our language (try to cross out all the animal metaphors out of the Iliad – you won’t have much left). Then they became the companions of our day-to-day lives, and in the end we crammed them into cages at the zoo against the backdrop of painted images of palm trees and swamps. Here they stare out with unseeing eyes, skimming over the faces of the people filing past them as if they were a museum exhibit. In such conditions, there is no way to exchange meaningful glances.

Wildness is now something we see in television and at the zoo, Berger believes. We have turned into spectators. The more we know, the further we move away from animals and animality. We no longer have any need to make eye contact with them. Berger argues that the gaze of a beast has become a cause for concern, even horror, in Western civilisation. After all, Homo sapiens is cultured, not just another type of fauna. To look into the eyes of a wild animal is to trigger a form of species-related narcissism, to prove how far we have come.

‘[The animals] in zoos […] constitute the living monument to their own disappearance,’ Berger concludes. In his view, this disappearance is the last metaphor given to us by wild species. The zoo is a place that marginalises. ‘All sites of enforced marginality – ghettos, shanty towns, prisons, madhouses, concentration camps – have something in common with zoos,’ Berger argues.

And he adds without pausing: ‘it is both too easy and too evasive to use the zoo as a symbol,’ as if wanting to justify the idea to which his reasoning leads. By marginalising the wild animal, by depriving it of its power to make us aware of our origins, we marginalise our own animality. ‘The rejection of dualism [of our nature] is probably an important factor in opening the way to modern totalitarianism,’ he concludes.

What is left when we kill the animal in us? A terrifying thought.

In the past, saving whales from extinction was about saving our morality. Today, saving the world is about saving Homo sapiens.

‘The animal inside, the creature that quakes at what twitches beyond the campfire light; that animal, too, needs protection.’ For me, this is one of the most shocking phrases in Giggs’s book. ‘When there are no places unfathomed by technology, when wilderness is excoriated in its entirety, something inherent to our humanness is also lost. We kill off the animal in ourselves, the part that belongs to the wildlife. We extinguish a species of wonder.’

For Homo sapiens, the threat is the human being.

The whales lead Giggs into yet another space. It is a space of twilight, four o’clock in the morning and a shore shrouded in mist. You may spot a humpback in the distance, its gleaming back, the flash of a great fin. Some will swear they saw a monster. Others will try to prove that it’s just a whale entangled in fishing nets.

But Giggs listens carefully to those who see monsters, because there is an important truth in the seemingly crazy desire to protect non-existent beasts. Are we capable of protecting what we have not yet recognised? A heroic act of restraint in the name of the invisible? If only to leave ourselves a chance for discovery, for delight, for mystery. Just so that the unnamed, the unexplored, the unknowable, the unconquered, the uncontrollable can exist alongside us.

I would take the matter even further: are we able to stand back? Whether we save the world depends not only on our effort to save it, but also on the effort to take one step back and make room for other creatures’ stories. To recognise them as legitimate, worthy of being heard and being saved. To see in animals beings who are like us, whose knowledge of the world developed over thousands, indeed millions, of years. If we were to abandon our species-related narcissism and just started to listen, what would a whale, a wolf, a chimpanzee or an octopus tell us?

This article was shortlisted for a European Press Prize in 2023 in the category of Public Discourse. It was originally published in Polish in Książki. Magazyn do Czytania. Translation by Voxeurop and Mark Ordon.

The First 126p was a very popular small car produced in Poland between 1972 and 2000. It became an icon especially during the period of the Polish People’s Republic It weighs around 630 kg.

Published 3 August 2023

Original in English

Translated by

Mark Ordon, Voxeurop

First published by Książki. Magazyn do Czytania

Contributed by Książki. Magazyn do Czytania © Katarzyna Boni / Książki. Magazyn do Czytania / Voxeurop

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Esprit revisits the philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty: including Guillaume Le Blanc on ‘incarnation’; Corine Pelluchon on eco-phenomenology; and Judith Revel on Merleau-Ponty, ‘the eternal runner-up’.

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.