When the first volume of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf was released on 18 July 1925, the book market was in deep crisis and the publisher didn’t expect much. Yet over 10 million copies of Hitler’s book were sold in Germany alone, and it became a commercial success in other countries too, including the United States. In 1947, the publisher reported that Hitler had earned around 15 million Reichsmarks (approximately 67 million euros) from the book, 7 million of which remained uncollected.

These facts are recorded by the Austrian historian Othmar Plöckinger in his 2011 study Geschichte eines Buches: Adolf Hitlers Mein Kampf (1922–1945). One of the myths Plöckinger dispels is that although the book sold well, it wasn’t actually read. On the evidence of library data, Plöckinger shows that Mein Kampf was read, criticized and, in some places, even celebrated.

The book was published by Franz-Eher-Verlag, run by Max Amann, Hitler’s former First World War superior. It was initially announced under the title ‘4.5 Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice: A Reckoning’. The ‘4.5 years’ referred to the First World War, in which Hitler had served as a corporal. The working title was mostly abandoned, what remained was the struggle (Kampf), a single word that encapsulated it all.

In 2018, I wrote that Mein Kampf could help us recognize modern fallacies and delusional conspiracy theories. I would no longer phrase it that way. There is no indication that an effective vaccine exists against false saviours. The culture of remembrance hasn’t been entirely ineffective, but we cannot sing hallelujah. The battle against lies, cowardice and stupidity is still enthusiastically waged from all sides, though mainly it seems to make oneself appear less stupid, cowardly and dishonest.

The past creates the present. But the present also creates the past, if only because our interpretation of the past is subject to constant change. If the political-religious messianism of the Israeli government continues, it is only a matter of time before Hitler’s mass murder of the European Jews will be understood as a pre-emptive war.

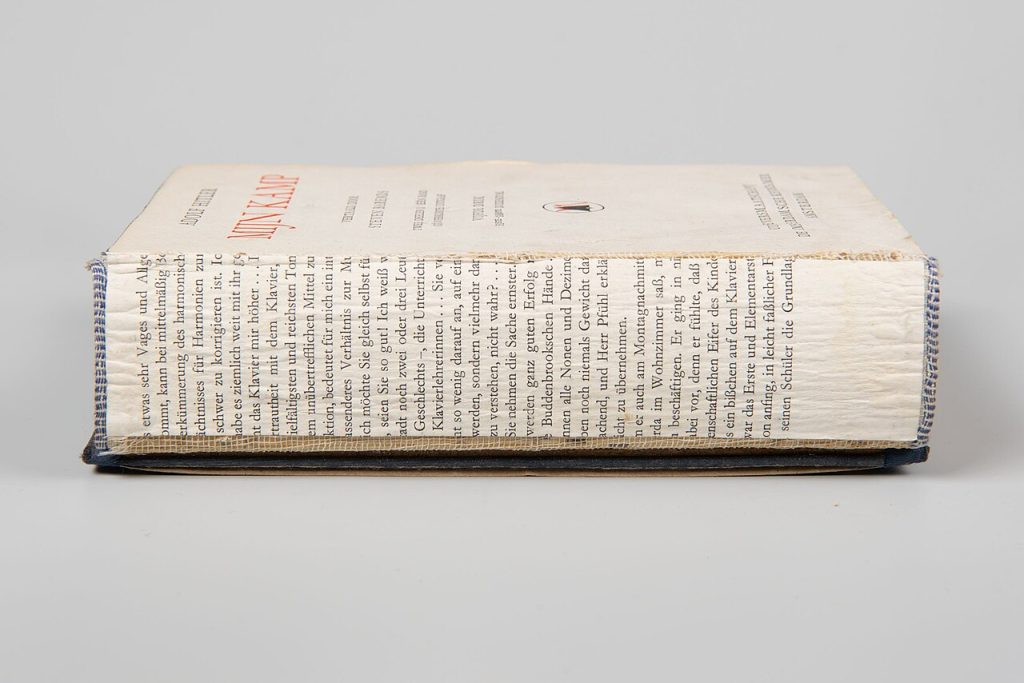

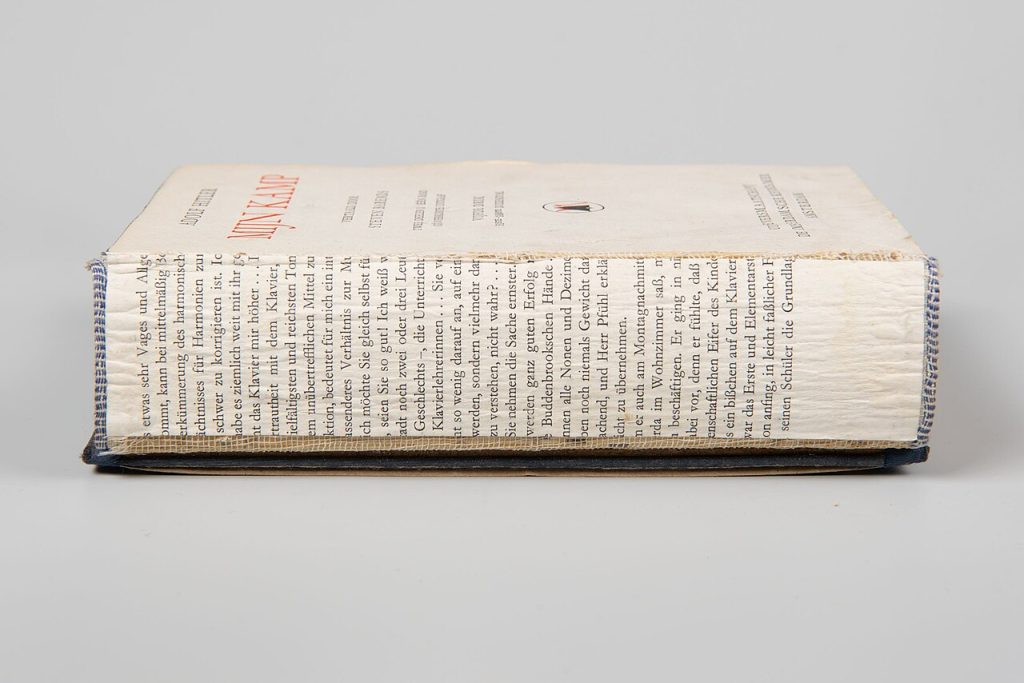

Dutch edition of Mein Kampf printed during the Occupation. The paper used for the spine comes from a novel by Thomas Mann. Image: Vrijheidsmuseum / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Beerhall messiah

Hitler’s political life began in Munich, where he discovered his oratory talent and where, after the bloody end of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919, the hunger for salvation may have been even stronger than elsewhere in Germany. Antisemitism flourished there more than in other parts of Germany.

As early as the 1920s, Hitler compared himself to Jesus: ‘We may be small, but once there was a man in Galilee, and now his teachings rule the world,’ he said in one of his speeches. According to Hitler’s biographer Volker Ullrich, his voice (a baritone) was his strongest weapon. Some listeners reported feelings of ‘religious conversion’ when listening to Hitler. He was said to be a ‘Luther’ for his time, though Ullrich notes that ‘copious amounts of beer’ likely made the audience more prone to such sensations.

From Charlotte Beradt’s 1966 classic Das Dritte Reich des Traums, we know that, by 1933, Hitler’s terror had already infiltrated the dreams of the German people. The Third Reich had penetrated the unconscious. Temptation had become fear, and redemption had become pure terror. Hitler’s battle against cowardice, lies, and stupidity would last twelve more years. By the end, between 70 and 85 million people were killed, including the six million Jews. We are still grappling with this legacy today.

Principles and lies

Even in the spring of 1945, when German cities were being firebombed and the Red Army’s artillery could be heard in Berlin, the faith of many Germans in their Führer remained unbroken. In The Rebel, Albert Camus wrote: ‘When principles fail, men have only one way to save them and to preserve their faith, which is to die for them.’ Many prefer losing a loved one to abandoning their principles. True loneliness begins when you wave goodbye to your last principle. And morality is so elastic that the fight against cowardice, lies and stupidity can sometimes take the form of terror.

Admitting you were wrong is so painful that most would rather not. Günter Grass served at the end of the War in the 10th SS Panzer Division ‘Frundsberg’. When I interviewed him two years before his death, he said he had believed he was fighting ‘for a just cause’. Even after Germany’s surrender, he dismissed the news as propaganda. It was only when Baldur von Schirach, the former Reich Youth Leader, admitted during the Nuremberg Trials that he had known about the mass extermination that Grass could finally admit he’d been wrong.

Grass referred to von Schirach in the interview as ‘my Reich Youth Leader’, as if a part of him had never truly left the Hitler Youth. A moment I’ll never forget. If you don’t die for the principles unmasked as lies, those principles – which can no longer rightly be called principles – turn into a wound that seldom truly heals. A societal wound.

Mass psychology

Anyone reading the scholarly edition of Mein Kampf today will be struck by how contemporary it is. The most striking passages concern the Jews and propaganda. Much of what Hitler says about propaganda still applies. He wrote that the NSDAP should not be a ‘helper of public opinion’, but a ‘ruler’. The party should not be a ‘servant of the masses …, but a master.’

Many political parties today, perhaps nearly all, aim to be masters of the masses instead of servants. Think about the perceived asylum ‘crises’. The most successful politicians are those who command public opinion. The less talented abandon their principles to gain favour. Propaganda masquerades as morality. Hitler keenly sensed that the lonely, resentful and disappointed crave community, and that nothing creates community as powerfully as a shared enemy, a scapegoat.

Antisemitism was just as virulent in prewar France as it was in Germany, but Hitler created a community of belief in which Jews were both Bolsheviks and capitalists, parasites and masters, visible and invisible. They were everywhere and nowhere, but above all: omnipotent. In Hitler’s view, the Weltjudentum was a world power, which meant that antisemitism had to become a world power too, concluded historian Salo Baron in 1942. We are still grappling with that legacy, too.

Forever bound to Hitler

Myths endure, especially when we believe we’ve overcome them. Mein Kampf’s critical reception wasn’t particularly enthusiastic. Rudolf Binding wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung that Hitler loved no one and had only one instinct: ‘the subjugation of the people’. His antisemitism was largely ignored or dismissed as secondary, except in Christian and Jewish press. Hans von Lüpke wrote in Kirche und Nationalsozialismus that the destructive influence of Judaism could not be fought by ‘glorifying one’s own race’.

Ullrich concludes his biography by stating that we are, in a way, ‘forever’ bound to Hitler, and that his life remains a warning of how easily ‘the rule of law and moral standards can be sidelined’. All the more reason to read his Bible.

Morality is elastic. One could say it’s a trampoline: the harder you jump, the higher you bounce. Those who cling to their principles become either heroes or mass murderers. Had warnings helped, Hitler might have been avoided. Anyone today who claims to fight lies, stupidity and cowardice should remind themselves that Hitler did so too. So did Günter Grass. For those, and I might say for those of us, who find comfort in the thought that we are merely compliant followers, only one certainty remains: the next saviour will come, and they will again put the elasticity of our morality to the test.