Popular culture in flux

Varlık 5/2025

In Varlık: how northern cultural hegemony is being challenged by Bollywood, Korean television dramas, K-pop and Nollywood; also, post-emotional human relationships and the aesthetics of uncertainty.

The outbreak of the Lebanese civil war fifty years ago inaugurated an era of nation-state collapse in the Arab world. In failing to mediate, the international community carries responsibility for the sense of impotence felt in societies in which violence dominated everything.

Historians are generally wary of commemorations – fireworks that dazzle the eye only to fade in the same instant. But they are also aware that ‘round number anniversaries’ can provide a unique opportunity to think about contemporary societies in their three-dimensional temporality: past, present and future. 1975 was one of those pivotal years in which events took place that, although not causally linked, each in its own way reflected the end of one historical era and the beginning of another in a particular part of the world.

On 13 April, tit-for-tat shootings in Beirut sparked off the Lebanese Civil War, which would go on to claim some 180,000 lives before coming to an end in 1989–1990, when Syria began its decades-long occupation of the country.1 On 30 April, the evacuation of American diplomatic staff in the famous ‘last chopper’ from the roof of the US embassy in Saigon – soon to be renamed Ho Chi Minh City – brought the Indochina wars to a close, and with them a long cycle of revolution in East Asia, while marking the beginning of the ‘boat people’ crisis and Cambodian genocide. And on 20 November, the death of the Spanish dictator Caudillo Francisco Franco signalled an end to last remaining regime founded in the 1930s as a branch of the international fascist movement.

The death of Hannah Arendt on 4 December made 1975 a year of loss for political philosophy. Recent events had amply demonstrated the relevance of her ideas. She had argued that ‘the meaning of politics’ was found not in raison d’état or the art of governing, let alone in geopolitics or projects for the creation a new society, but in freedom itself.2 Known for her Athenian sympathies, Arendt was perhaps also the first thinker to highlight the antithetical nature of violence and politics,3 and how the presence of the one attests to the non-existence or disappearance of the other.

At the time of Arendt’s death, Spain was transforming itself into a democratic society and equipping itself with a new institutional architecture that stripped ‘revolutionary violence’ of all legitimacy. Concurrently, the Arab world was entering upon a liberticidal and politicidal cycle in which the agora – that partly imaginary institution so dear to Arendt – would be destroyed by tyranny and war.

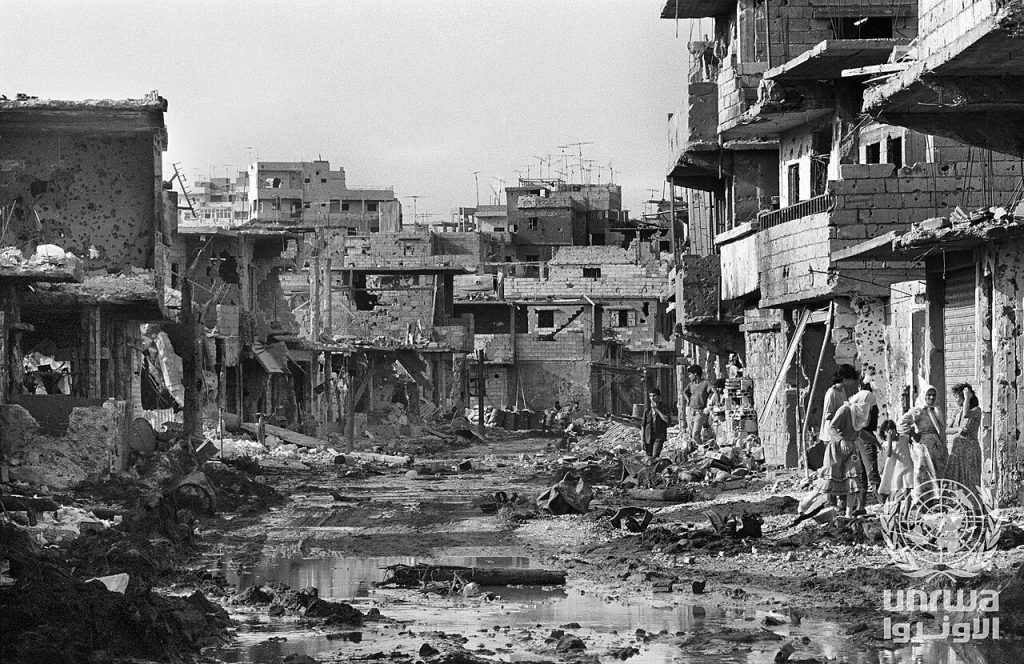

A main street in Shatila camp during the July ceasefire, Beirut, Lebanon. © 1986 UNRWA Photo by H. Haider. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Lebanese Civil war was preceded by a series of momentous events in the region, beginning in June 1967, when the Israeli military defeated the Arab coalition forces and seized what was left of historic Palestine. Then, in 1968 and 1969, ‘progressive’ coups brought Hassan al-Bakr and his protégé Saddam Hussein to power in Iraq and resulted in the eccentric Muammar Gaddafi taking over in Libya. In 1970, the ill-advised attempt by Palestinian revolutionaries to overthrow the ‘reactionary’ King Hussein of Jordan ended in crushing defeat following their betrayal by Hafez al-Assad, then commander of the Syrian air force, who abandoned them to their fate. This episode, which has gone down in the annals of history as ‘Black September’, claimed thousands of lives and radicalized part of the Palestinian liberation movement.

Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian president and leader of the Arab ‘resistance camp’, was deeply affected by the conflict, and died of a heart attack on 28 September. Shortly afterwards, Hafez al-Assad ousted his comrades from power in another coup, establishing a dynasty that would not be overthrown until December 2024. Finally, in 1973, came the Yom Kippur War, which historian Henry Laurens described at the end of the last century as the first victory of the Arab states in their conflict with Israel and simultaneously their last – and heaviest – defeat to date.4

The Lebanese Civil War brought this short but intense period in the history of the Arab world to a close. Initially, it appeared to conform to the political grammar of its time, with a pro-Palestinian Left, made up mainly of Muslim actors, pitted against a Right mainly drawn from Christian communities that advocated, if not an alliance with Israel, then at least a policy of neutrality towards it.

But the conflict was more complex than this, concerning as it did the question of Lebanese ‘national’ identity. Who would define such a thing, and which part of Lebanese society would pay the price? What form should the Lebanese state – and Lebanese society – take? What territorial divisions, and what system of confessional and supra-confessional representation, would allow for the coexistence of the country’s Christian, Muslim and Druze communities? Should Lebanon become a base for armed Palestinian resistance or a buffer-zone under Israeli control? Should it be an independent state or part of a larger Syrian–Lebanese entity, forcefully imposed by the Syrian ‘Social Nationalists’?

The dividing lines shifted daily, rendering any attempt at a definitive or binary reading of the situation futile from the start. For example, in August 1976, under siege from Maronite militias, the inhabitants of the Tel al-Zaatar Palestinian refugee camp asked Hafez al-Assad for help. Assad intervened, but in support of their Maronite opponents, who massacred some 2,000 Palestinians. In June 1982, the violence escalated further with the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon, followed by the expulsion of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) to Tunis in August. Then came the assassination of Lebanese president Bachir Gemayel on 14 September, who had allied with Tel Aviv more out of opportunism than conviction and, finally, the founding of Hezbollah with the support of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

The Lebanese civil war began as an inter-community conflict, but also became an intra-community conflict as the old Sunni, Shiite and Maronite elites were physically eliminated or politically marginalized by younger generations in their own communities. The fratricidal war thus turned parricidal. The Palestinians, for their part, also emerged politically and morally damaged: their refugee camps became battlefields between rival factions, supported or manipulated to varying degrees by Damascus. With the foundation of Hamas in 1987 by militants inspired by Abdallah Azzam (1941–1989), the theorist of the Afghan jihad and a forerunner of Osama Bin Laden, the seeds of a bloody future conflict were sown.

Unlike the Asian and Latin American guerrilla wars of the 1950s and 1960s, which had occupied the imaginaries of Arab leftists, this was a war fought by militias that took place in the city. It was an ‘urbanicidal’ conflict, because it destroyed ways of living in and transforming the city. As Élizabeth Picard has shown,5 militia violence is both the cause and the consequence of the partitioning of the urban fabric into territorial enclaves. Fighters, united by an organic socialisation, develop a specific ethos that relieves them of responsibility. Drawing on a generational dynamic to dismantle hierarchical, economic, or social relationships, they seize the fiscal resources and means of violence within a given neighbourhood. The ‘old guard’– the former elites and the urban middle classes – lack the resources to obstruct this form of war, let alone provide political responses to the violence to which they are subjected by their ‘children’.

Was this the end of all life and all the joys of life in Lebanon? Far from it. In Tony Scott’s Spy Game (2001), Robert Redford and Brad Pitt are still able to enjoy excellent service in a Mexican restaurant in Beirut during the ‘War of the Camps’ in 1985, despite the bombings and the multiple checkpoints that reconfigure the urban topography according to the ebb and flow of combat. The commanders were also able to maintain a luxurious lifestyle through their access to certain resources: while their fighters were killing one another, they made sure their trusted technocrats sat on the board of Middle East Airlines, sharing out the dividends amongst themselves.

The civil war broke out just as the artist Etel Adnan (1925–2021) was starting work on a remarkable epic poem, or what might better be described as a verbal torrent: The Arab Apocalypse.6 It is addressed to a ‘people with no calendar’, the ‘Arab people’, who live in a land and under a sky where all is ‘sun’, but all sun is tainted with darkness and ugliness. Jesus has returned, but to witness ‘a succession of graves in the centre of the city’,7 rather than to save it. While he is not sentenced to death again, as in Dostoevsky’s story of the Grand Inquisitor, ‘a sun-ambulance carries [him] to the insane asylum … Close to the monkeys.’

In a world in which all reference points of trust in time and space have disappeared, absurdity prevails over cruelty, while also being produced by it:

The mosque has launched its unheated prayer. Lost in the waves.

The street lost its stones. Brilliant asphalt. Useless roads. Dead army. Snuffed is the street. To shut off the gas. Refugees with no refuge no candle.

The procession hasn’t been scared. Time went by. Silent Phantom.

…

Beirut is eaten by civil war children listen to the roar of cannons matter in fury turns in circles

in the big void of the planets Beirut wallows in misfortune

HOU!

HOU!

HOU!

Beirut bleeds matter circles in tornadoes on nebulae’s surfaces

O Milky Way!

more blood than milk more pus than wine

Beirut, the theatre of a ‘war without revolution’, is a disappointment to the old revolutionaries, those who believed in ‘revolutionary war’ on the grounds of their moral code and universalist commitment. It is a place where ‘death bedecked in its jewels has ridden in on horseback for a very long stopover’; where men with Kalashnikovs expend ‘millions of dollars of hatred and tons of sorrow … Tons of despair and gigantic rivers filled with our collective tears.’ It is a dystopian land in which ‘they killed the dream with an axe! With an axe! With an axe!’

While the capital’s apocalypse is primarily a Lebanese one, it is also a Palestinian one, foreshadowing events that will go on to be repeated over and over, decade after decade:

… the sun a column of stone beating down on the martyr’s head

Fedayeen of a cause stillborn of an anti-matter sun

In the big holes of Space death chambers are being made ready

The Palestinians will be put on a ship to the moon

They sing their own requiem in the rocket that takes them away

Piloted by the angels of evil in Space itself they lose themselves.

Finally, the apocalypse is deeply ‘Arab’, and above all Syrian:

… the executioner washed his hands so as not to contaminate the hanged

In the public square in Damascus three trees grew in four hours

The generals were present the tourists at the windows

The people the people the people the people said Blessed be Hell.

Beirut was living through the apocalypse, going to bed and waking up to scenes that disturbed its sleep. But this was an apocalypse without revelation: it turned language, which George Steiner considered the bedrock of civilisation,8 into a tool of death, thus excluding the very possibility of peaceful otherness. It was sterile, saying nothing of the past other than its absurdity, and heralding nothing of the future other than the absurd.

Violence dominated everything but resolved nothing;9 while it seized on ‘universal freedom’, this was a freedom whose ‘sole work and deed’ – as Hegel put it in Phenomenology of the Spirit – is ‘death, a death too which has no inner significance or filling, for what is negated is the empty point of the absolutely free self. It is thus the coldest and meanest of all deaths, with no more significance than cutting off a head of cabbage or swallowing a mouthful of water’: a ‘meaningless’ death.10

Other societies in the Arab world would go on to experience a similar phenomenon: in the 2010s, northern Yemen was taken over by a sectarian militia, Syria was home to some twelve hundred militias, and Libya three hundred. In Iraq, a coalition of forty Shiite militias took power, alongside the Islamic State. But Lebanon experienced oblivion and impotence long before these lands of violence. Its civil war showed that the ‘international community’ was unable to mediate the conflicts taking place in this part of the world. Israel’s support from the United States and, to a lesser extent, Europe, was of course never in question, any more than it is today. The feeling of impotence this produced that would later turn into indifference.

While the Lebanese Civil War was inseparable from the Palestinian question, its many ramifications and transfigurations gave it much broader significance. For it was the Lebanese state – the Westphalian entity expected to pacify its space of sovereignty and monopolize the means of coercion – that collapsed in on itself, in both principle and practice.

A state is primarily defined by its ability to unify time and space, while allowing multiplicity (of class, age, and gender) to have its own time and space. The purpose of a militia, conversely, is to take apart this unity and undo the forms of socialisation without which a society cannot exist. Under militia rule, time becomes synonymous with violent uncertainty and has no horizon other than the quest for survival. Space, meanwhile, either shrinks to the point of prohibiting all movement, or expands, forcing individuals and groups to migrate from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, from city to city, from one place of asylum to the next, whether in nearby Cyprus or far-off Australia.

A clearly defined state, anchored in the long-term, presupposes huge sums of money and a bureaucracy or technocracy capable of raising or acquiring them. A militia, on the other hand, can make do with modest resources, if necessary taken directly in kind. A state army is founded on command structures, hierarchy, standards and procedures; but a militia, fighting in a profoundly pacified and therefore defenceless urban space, can be effective with just a few hundred men, and is able to deploy at the slightest signal from a nearby authority. While militia and state are positioned on a single continuum of coercion and violence, they are directly opposed to each other: their coexistence necessarily means the transfiguration of the state itself into a new militia force.

The apocalypse that Adnan describes is an apocalypse without revelation, at least for now. But when the revelation does eventually come, it will be not to herald a break with the past, but simply to bury the past, which held no promise for the future:

When the sun will run its ultimate road

Fire will devour beasts plants and stones

Fire will devour the fire and its perfect circle

When the perfect circle will catch fire no angel will manifest itself STOP

The sun will extinguish the gods the angels and men

And it will extinguish itself in the midst of its daughters

Matter-Spirit will become the NIGHT

In the night in the night we shall find knowledge love and peace.

Fifty years ago, as Spain emerged from its long night and began on a path to implementing a politics of freedom, the first shootings, followed by promises of exponential retaliation, signalled the entry of Arab society into its own night, confirming Arendt’s view that a violent society cannot be a political society. Her analysis can also be understood as a message, one that is more relevant than ever to Arab societies under their present reign of Thanatos.

Published in cooperation with CAIRN International Edition, translated and edited by Cadenza Academic Translations.

See Dima de Clerck and Stéphane Malsagne, Le Liban en guerre. De 1975 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2024).

Hannah Arendt, The Promise of Politics, edited by Jerome Kohn (New York: Schocken Books, 2005), p. 120.

Ibid. pp. 164 – 165: ‘In dealing with other states or city-states, the polis as a whole acted with force, and thus in its own eyes acted “unpolitically”.’

Henry Laurens, Paix et guerre au Moyen-Orient. L’Orient arabe et le monde de 1945 à nos jours (Paris: Armand Colin, 1999), 288 – 292.

Élizabeth Picard, ‘Liban, la matrice historique’, in Économie des guerres civiles, edited by François Jean and Jean-Christophe Rufin (Paris, Hachette, 1996), pp. 62 – 103.

Etel Adnan, L’Apocalypse arabe (Paris: Galerie Lelong & Co, [1980] 2021). See Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, ‘Breaking the Silence: Etel Adnan’s Sitt Marie Rose and The Arab Apocalypse’, in Poetry’s Voice – Society’s Norms: Forms of Interaction between Middle Eastern Writers and Their Societies, edited by Andreas Pflitsch and Barbara Winckler (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2006), pp. 201 – 210.

Translator’s note: Where possible, we have referred to Etel Adnan’s own translation of her poem. In other cases, we have translated the French ourselves.

George Steiner, Extraterritorial: Papers On Literature and the Language Revolution (London: Penguin, 1975).

See Hamit Bozarslan, ‘Quand la violence domine tout mais ne tranche rien. Réflexions sur la violence, la cruauté et la Cité’, Rue Descartes 85 – 86 (2015): pp. 19 – 35.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Phenomenology of the Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1998 [1807]), p. 360 and 362.

Published 11 July 2025

Original in English

Translated by

Cadenza Academic Translations

First published by Esprit 6/2025 (French version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Esprit © Hamit Bozarslan / Esprit / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

In Varlık: how northern cultural hegemony is being challenged by Bollywood, Korean television dramas, K-pop and Nollywood; also, post-emotional human relationships and the aesthetics of uncertainty.

In a world saturated with information, stimuli and industrialized noise, silence can be a reprieve – a vital force that is at least as clear as the ‘loud’ slogans raised at protests and rallies.