In Turkey’s official historical narratives, women’s struggle for liberation from the oppression of the patriarchy aligns with the age of the Republic. According to this ‘secular, republican and modernist’ viewpoint, the ‘founding fathers’ granted women various rights and aided them in achieving equal standing as citizens, paving their way to freedom as individuals.

What was later labelled ‘state feminism’ undeniably facilitated Turkish women’s entry into the public sphere and provided them with numerous rights and opportunities. However, the idea that these rights were ‘bestowed’ has consistently burdened Turkish women, impeding their ability to be more assertive, to mobilize, and to develop a critical stance towards the official ideology. For the same reasons, it took considerable time for there to emerge an awareness and understanding of the history of women’s struggle for equality and freedom before the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

In the 1980s, as the feminist movement gained momentum, it made a ground-breaking discovery: that not only had there been a bold and vocal organization in the Ottoman Empire that could be aptly termed a ‘women’s movement’, but that this also had a causal link with contemporary Turkish feminism. The realization that the seeds of a struggle characterized by the motto ‘rights are not given but taken’ were planted much earlier than the Republic itself became a wellspring of courage and resilience. From now on, women’s history began to be perceived outside the official narrative.

Pioneering women

First-hand accounts appeared of trailblazers like Fatma Aliye, Emine Semiye, Nezihe Muhiddin, who advocated for women’s education, marital equality and freedom from the constraints of the hijab. But for political reasons, it was much later that we encountered the Armenian activists Mari Beyleryan and Zabel Yesayan, or the Greek feminist Athina Gaitanou-Gianniou. Together within the non-Muslim community, all three fought persistently against the multiple discriminations tied to their ethnic and political identities. Political factors also delayed the recognition of leftists like Sabiha Sertel, Suat Derviş and Fatma Nudiye Yalçı.

In the realms of music, theatre, opera and cinema, we only realized much later that the first-generation non-Muslim women, defying oppression and professional barriers, had bequeathed a comfort zone to the next generation of Muslim women artists. In 1923, Nezihe Muhiddin and thirteen women friends established the Women’s People Party with the optimistic belief that, under the new regime, women would attain equal political rights. While the Republican People’s Party, founded the same year, was recognized as Turkey’s first political party, Nezihe Muhiddin and her friends were banned. The Women’s People Party was forcibly transformed into the Turkish Women’s Union and its members tasked with shaping the image of the ideal Republic woman, whose characteristics and boundaries were delineated by men.

The corrosive and exclusionary process that left Nezihe Muhiddin isolated and grappling with mental crises also kept women away from political involvement for an extended period. It was only in 1935, a year after men consented to grant women the right to vote and run for office, that the first women deputies entered parliament. Eighteen women occupied the back benches, their presence marked by anxiety and awkwardness. It wasn’t until the 1970s that, as members of the Workers Party of Turkey under the leadership of Behice Boran, women would truly be empowered as representatives of the people and take their place in Parliament.

Allowed to leave the home

The Law on Unification of Education of 1924 paved the way for women to participate in education, while the Turkish Civil Code of 1925 introduced regulations regarding polygamy, property division and divorce, all favouring women. However, the man remained the head of the family. Many aspects of women’s lives, such as entering the workforce or childbearing, still depended on the decisions and permission of men. The first international women’s congress was convened in 1935, under Atatürk’s patronage. Representatives from 39 countries were invited to discuss the topic of equality. Although a manifestation of state feminism, this initiative was an important opportunity for women to address shared problems and seek solutions.

But the impact of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the rise of fascism and Nazism in Europe was also evident in Turkey. Women were excluded from public life. The prevailing discourse glorified fertility and encouraged family values and the idea of healthy generations strengthened solely by the caregiving work of women. The national education curriculum, sports and the press all promoted this perspective. Although attempts were made to ensure equality in the workplace with the Labour Law of 1936, economic depression and political turmoil served as convenient excuses to keep women away from working life. The only professions deemed suitable for women were those involving emotional labour and care work. They were mostly dominated by same-sex relations and characterized by fixed working hours: teaching, secretarial work, nursing, caregiving, etc. Women with lower levels of education worked in weaving, food, alcohol and tobacco production workshops, as well as in a small number of factories.

Even during the Ottoman Empire, women had access to formal education, albeit limited. A small number of young women from the elite class attended schools that provided western education, referred to as ‘missionary schools’. The feminist author Halide Edip, for example, was one of first Muslim-Turkish students at The American College for Girls. Despite condemnation and even threats, her father, a broad-minded bureaucrat, ensured that she attended . Mina Urgan, the philologist and socialist politician, also received a western education, first at the Lycée Notre Dame de Sion Istanbul and later at the Robert College.

The young women who went to these schools were exposed to a western curriculum as well as a culture of democracy. They would later become prominent figures in politics, arts and culture, diplomacy and sports. These schools drew criticism from nationalist and conservative groups not only because they were suspected of spreading Christian culture, but also because their education system fostered individualism and freedom. Today’s criticism of Boğaziçi University (Bosphorus University) and the reaction to the Boğaziçi protests in 2021 can be traced back to this antagonism.

Feminism and the New Left

In the 1970s Turkey witnessed an unprecedented strengthening and legalization of the left. This reflected the momentum gained by the New Left movement internationally. The Turkish Communist Party (TKP) and the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP) were organized nationwide, the struggle for the rights of the working class was shaped in the light of leftist literature, and leftist parties were represented in the Parliament. It was during this time that women began to actively participate in the leftist parties as champions of class politics and the ideal of revolution.

Behice Boran became head of the TİP in 1970, but not all women were as influential as she was in the management levels of leftist organizations and parties. It was the Progressive Women’s Association (İKD), founded within the TKP in 1975 with the slogan ‘equality, progress, peace’, that prepared women on the left for the feminist struggle. Its members marched with the belief that the imminent revolution would solve not only all the problems of the country, but also the issues they were facing as women. Any objections were seen as petty bourgeois sensitivities and were repelled by the male leaders of the party organizations and even by the women themselves. This mentality dominated the leftist literature, newspapers, magazines, literature, cinema and theatre of the period. The İKD became visible in the public sphere thanks to a robust organizational structure. However, its rhetoric reflected that of the TKP and was usually constructed by men.

An explosion of publications contributed to the atmosphere of political diversity and relative freedom in the ’70s. These served as platforms for political discussions and the organization of protests, as well as channels for introducing the public to alternative political currents. By the end of the decade, the İKD’s magazine Kadınların Sesi (Women’s Voice) and the similarly oriented Demokrat Kadın (Democrat Woman) had begun to address – albeit cautiously – issues such as women’s position in the family, exploitation at work, physical integrity and harassment and rape, while still focusing primarily on the class struggle. A group of Kurdish women also began to raise their voices against gender-based and ethnic discrimination, expressing their grievances through street protests and in the magazines they published. Finally, there emerged during this period a group of Muslim women labelled ‘Islamist feminists’ by the press, who actively contested the interpretation and appropriation of Islam by men.

Women shaping their own world

As with every political movement, publishing – and particularly magazine publishing – played a vital role in sustaining feminism in Turkey from the 1970s. However, the movement came up against the constraints of tradition, religion, morality and patriarchy, and was often regarded as marginal and threatening. Under such circumstances, it became clear that magazines that adopted a more moderate style to convey women’s demands would have a wider influence. Elele magazine (the name ‘hand-in-hand’ was selected through a readers’ contest) emerged towards the end of 1976 and evolved into a publication that, in a gentle tone, elucidated the challenges faced by women for a broader readership, offering possible solutions.

The magazine was part of the Hürriyet Group. Before Elele, women’s magazines had predominantly covered subjects like childcare, health and motherhood. Elele transformed their approach by presenting these topics in an encyclopaedic format crafted with input from specialists. Most notably, Elele introduced a ground-breaking sex guide explicitly addressing women. The magazine not only reminded readers of their duties as mothers and wives but also rekindled the struggle for rights and equality. While these issues had been largely addressed in the West through hard-fought battles waged by the first wave of feminism, they had only been a minor aspect of the opposition in Turkey. The demand for the legalization of abortion, a topic that would later be persistently brought up in Kadınca and Kim, was voiced for the first time in Elele in a dossier prepared by Selma Tükel. The threat posed by the abortion ban, jeopardizing women’s health through illegal procedures, was discussed in detail, supported by examples and expert opinions.

The reader interest Elele had attracted and the widespread popularity of women’s magazines worldwide prompted the launch of another women’s magazine two years later: Kadınca. Published by the Gelişim Publishing Group, Kadınca became one of the most influential periodicals in the history of the press. Unlike Elele, Kadınca liberated women from the confines of family life and adopted a publishing approach that focused on various aspects of womanhood. It rebelled to some extent against dominant gender relations and patriarchal culture. After Kadınca was shut down, the same team would publish Kim and for a long time continue along the same trajectory, even pushing it further. Some of its members also contributed to Pazartesi magazine, which played a key role in the history of feminism.

The women’s movement finds an outlet

With the military coup on 12 September 1980, all political activities, organizations and publications were banned. The public sphere and the political stage were closed to both the right and the left for an extended period. The coup’s prohibition on politics provided the women’s movement, which was not yet recognized as a political initiative, with fewer obstacles. Having been excluded from decision-making processes in male-dominated political organizations, relegated to logistical support and ignored, women finally had the opportunity to give the feminist struggle its name. Young women reporters and writers, expressing their personal rebellions almost instinctively in widely read publications, played a vital role in amplifying the voices and demands of women at the forefront of this struggle. Though not labelling themselves as feminists explicitly, this group of women engaged in a quest for women’s rights, identity, dignity and freedom.

In establishing the theoretical underpinnings of the feminist movement, the magazine Somut, published by YAZKO from 1981 to 1987, played a crucial role by providing a space for the self-expression of this movement. This endeavour was followed by the formation of Kadın Çevresi Publications in 1983. Initially rooted in translations of western literature, its list evolved to include original literary works. Duygu Asena’s Kadının Adı Yok (Woman Has No Name), published in 1987, allowed the author – who did not identify as a feminist and had limited engagement with the various parts of the movement – to communicate the aspirations for women’s liberation to a broad audience. The book underwent numerous editions and was even adapted into a film.

Throughout this journey, initiated by Kadınca and sustained by Kadınının Adı Yok, Turkey embarked on a profound exploration of womanhood. The groups formed during this era served as platforms where women actively challenged patriarchy and the societal structure, engaging in a profound reckoning and politicized the personal sphere. As these groups evolved, they somewhat patronisingly came to be known as awareness-raising events.

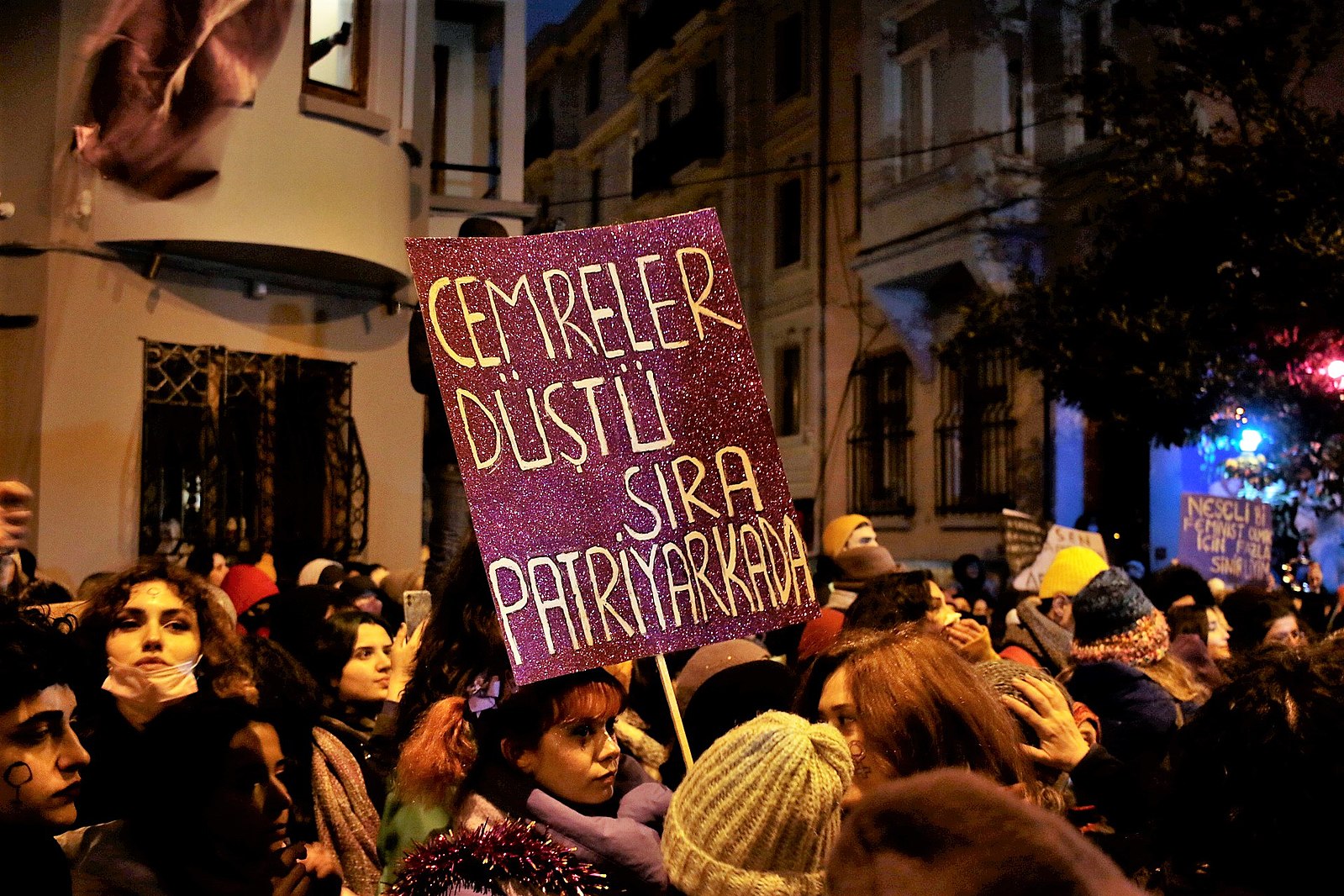

The ‘Women! Solidarity Against Beatings’ march in the spring of 1987 marked the first street protest following the coup d’état of 1980. Kaktüs magazine, first published in 1988, was hailed as the manifesto of socialist feminists. Women involved in class politics could now integrate feminist principles without deviating from this overarching perspective. In 1989, a women’s congress was organized under the initiative of the Human Rights Association. In the same year, the Purple Needle campaign was launched. Women took to the streets brandishing purple needles, symbolizing their resistance against harassment, rape and all forms of male aggression, while advocating for the legitimacy of self-defence. It proved to be a compelling and impactful mobilization effort.

The 90s and the rise of identity politics

During the latter half of the 1980s, the ANAP government, led by Turgut Özal, began adapting to the liberal order of the post-Cold War era. This politically intricate period, rife with challenges, created room for identity politics. Although criticized by advocates of class-based politics, identity politics served as an outlet for Kurdish and Alevi groups in the 1990s, as well as the non-Muslim population of Turkey seeking representation and rights. Fuelled by momentum from the 1970s, the Kurdish women’s movement began publicly addressing conflicts in eastern and south-eastern Anatolia, along with instances of torture in Diyarbakır Prison, whenever an opportunity arose.

Roza magazine stood out as one of these platforms. In the 1990s, Muslim women affected by the Regulation on Dress Code in Public Offices, famously known as the ‘türban ban’ enacted after the 1980 coup d’état, gained more visibility. Simultaneously, the LGBTI movement asserted its identity through the pages of Kaos GL magazine. During this time, the discourse evolved, emphasizing that feminism served as an ideological foundation not only for women’s rights but also for broader struggles against patriarchy, labour exploitation, environmental degradation and all forms of oppression, including racism and animal cruelty. The presence of socialist, Muslim, anarcha-feminists and others with diverse perspectives indicated the existence of a spectrum of feminisms rather than a singular definition. Journals such as Feminist Politika, Amargi and Pazartesi played crucial roles as guiding lights during these transformative years.

21st century challenges

At the start of its prolonged rule in 2002, the AKP promised to support marginalized groups, address hate speech and violence, and initiate efforts in favour of identity politics. In its early years, there were indeed positive developments in this direction, garnering support from diverse political segments, including leftwing dissidents. The signing of the Istanbul Convention in 2011 generated optimism as a document aimed at empowering women and the LGBTI community, particularly in combating domestic violence and advocating for equal rights. Positive effects were indeed witnessed in practice.

However, the AKP’s authoritarian consolidation, initiated with the Gezi protests and consolidated during the 2015 elections, resulted in setbacks in the fight for gender equality. The growing strength and legitimization of the women’s and LGBTI movement prompted unease among the AKP’s coalition partners and the majority of voters. The Association for Women and Democracy (KADEM), established in 2013 under the slogan ‘Equality in existence, justice in accountability’ purportedly to uphold and propagate the AKP’s gender policies, has long functioned as the ruling party’s sanctioned women’s organization. However, when the government declared its intention to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention in 2021, the organization’s critical stance altered to some extent. In the campaign to shift from gender equality to gender justice, and to prioritize family-centric gender policies, KADEM struggled to deviate significantly from the AKP’s agenda.

Rightwing politics, particularly the AKP-MHP coalition – which like any ideological stance, incorporates women’s bodies into political narratives for strategic purposes – has made it its goal to undermine the women’s and LGBTI movements. This is achieved by making references to the türban ban, portraying LGBTI individuals as a threat to family values and hereditary continuity, and encouraging conservative women to reject opposition movements. In the 2023 general elections, the AKP secured a new victory by forming alliances with conservative and nationalist parties, indicating continued suppression and antagonism toward the women’s and LGBTI movements.

Despite claiming to have implemented measures to address the increasing violence against women, the government attempts to discredit civil society organizations advocating for gender equality by accusing them of ‘receiving funds from organisations acting against the interests of Turkey’ and ‘threatening the family’. Nevertheless, women’s organizations and initiatives (such as EŞİK, Women’s Coalition, Platform to Stop Femicide, University Women’s Collective, Women’s Defence Network, Women’s Solidarity Foundation), which constitute one of the most robust opposition groups in recent years, are gaining strength. With less to lose both globally and within the country, they are steadfastly affirming through their discourse and actions that they will not back down in their struggle for equality and freedom.