Expectations, standards, and requirements in higher education vary from country to country. In the third episode of the Knowledgeable Youth podcast Ukrainian students embark on the complex subject of tertiary education.

Poland regained its independence after the First World War. Despite developing multiple ambitious visions, it failed to recreate its former state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and to reconstruct the map of western Eurasia.

In 1918 a newly independent Poland appeared on Europe’s stage with a complex and ambitious vision to rebuild the western parts of the former Russian Empire. The new opportunities that Poland saw were the results of Germany’s and Russia’s defeat in the First World War. Poland, seeing a geopolitical vacuum in the East, came up with three visions. The first was a recreation of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth through a federation of Poland, Belarus, and Lithuania, (and maybe Latvia) that would have had been closely allied with an independent Ukraine. The second vision, called Prometheism, was the liberation of non-Russian nations. At a later stage it was also to offer support to Russian non-communist leftist groups. The third vision, Intermarium, foresaw co-operation among the newly independent states located between the Baltic and the Black Seas, and possibly the Adriatic Sea.

These visions became the foundation of Józef Piłsudski’s foreign policy in the years 1918-1921. Piłsudski is widely considered to be the father of Poland’s independence and was affiliated with the Polish Socialist Party. Before 1918 he was convinced that imperial Russia should be seen as the biggest threat to Polish independence, no matter who the ruling elite were. After 1918 Piłsudski had hoped that a reconstruction of western Eurasia would bring about a guarantee of Poland’s independence. His view was opposed by Roman Dmowski, the leader of the National Democracy party – a nationalist party propagating a vision of Poland as a regional power dominated by ethnic Poles. Unlike Piłsudski, before the First World War Dmowski treated Russia as a potential ally against Germany, which he believed was Poland’s greatest enemy. The rivalry between the two politicians and their visions dominated Polish politics from the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th century.

The ideas promoted by Piłsudski – mostly associated with the Second Polish Republic which lasted from 1918 until 1939 – were deeply rooted in pre-modern Poland. The concept of a Lithuanian-Polish federation was inspired by the 1386-1569 dynastic union as well as the later Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which lasted from 1569 to 1795. The latter was a multi-ethnic and multi-religious state, one that hosted even Muslim Tatars on its territory – quite unusual for a Christian state at that time. However, the Commonwealth gradually became dominated by Catholic Poles.

The concept of Intermarium was also linked to the experience of the Commonwealth and especially the Lithuanian dynasty of the Jagiellonians, who ruled Poland and Lithuania from 1386 to 1569. In fact, the term Intermarium (in Polish Międzymorze, meaning in between the seas) was first used in 1564 in a poem by the great Polish poet, Jan Kochanowski. It was used to describe the state’s location between the Baltic and the Black seas, Poland’s and Lithuania’s territorial reach between the early 15th century and the 16th century. For Kochanowski it was a symbol of their greatness. It is worth adding that at the turn of the 16th century the Jagiellonian dynasty also ruled the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Hungarian Kingdom which had access to the Adriatic.

Intermarium was also an attempt to establish an anti-Moscow alliance, which would have included states located on the North-South axis, between the Baltic and Black Seas. At certain periods it included Lithuania-Poland, Sweden, the Duchy of Livonia, the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire. The belief that Poland’s power came from its vast territory stretching between seas became an element of national identity after Poland lost independence in 1795. It was based on the prophecy of the legendary Cossack Wernyhora, who foresaw Poland’s rebirth. However, the key role in this prophecy was to be played by… Islamic Turkey.

Prometheism, as the name suggests, was a vision inspired by Prometheus, who was chained to a rock in the Caucasus for stealing fire and giving it to humanity. As a foreign policy concept, Prometheism assumed the liberation of non-Russian nations from the oppression of the Tsarist rule. These nations were then to become brothers in arms, despite their religious and ethnic differences. They were to be supported in their fight by Russia’s neighbours.

The term Prometheism was coined in the interwar period, but its roots date back to the early 18th century when two Ukrainian Cossack hetmans, Ivan Mazepa and Pylyp Orylyk started to co-operate with Sweden, Poland, the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire, as well as the mountaineers of the Northern Caucasus, the Volga Tatars, Bashkirs and the Don Cossacks. This tradition was carried on by Polish political emigration in the 19th century, led by Prince Adam Czartoryski. He invoked a concept of different rings for opposing Russian imperialism. Two of them were within Russia and included Ukraine, the Don Cossacks, Latvia and Estonia (the first ring) as well as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (as it existed before Poland’s partitioning), Finland, the Tatars, the Northern Caucasus and Central Asia (the second ring). The external ring was made up of the Russian empire’s neighbours: Sweden, Austria and Turkey.

Piłsudski and his party further developed this idea at the turn of the 20th century, believing that ethnic the heterogeneity of the Russian empire was its Achilles’ heel. According to him, the division of Russia along ethnic lines should constitute a key goal for Poland. To achieve this, Piłsudski used slogans of the social revolution which erupted in Russia and also reached Polish lands. The revolution, in his view, could bring about a complete collapse of the Russian empire. As a result, ‘independent states would emerge, including a Polish-Lithuanian state, a Latvian, an Estonian, a Finnish, an Armenian and maybe even a Tatar state. All of these states were to form a union which would squeeze and suffocate Moscow’ – he suggested.

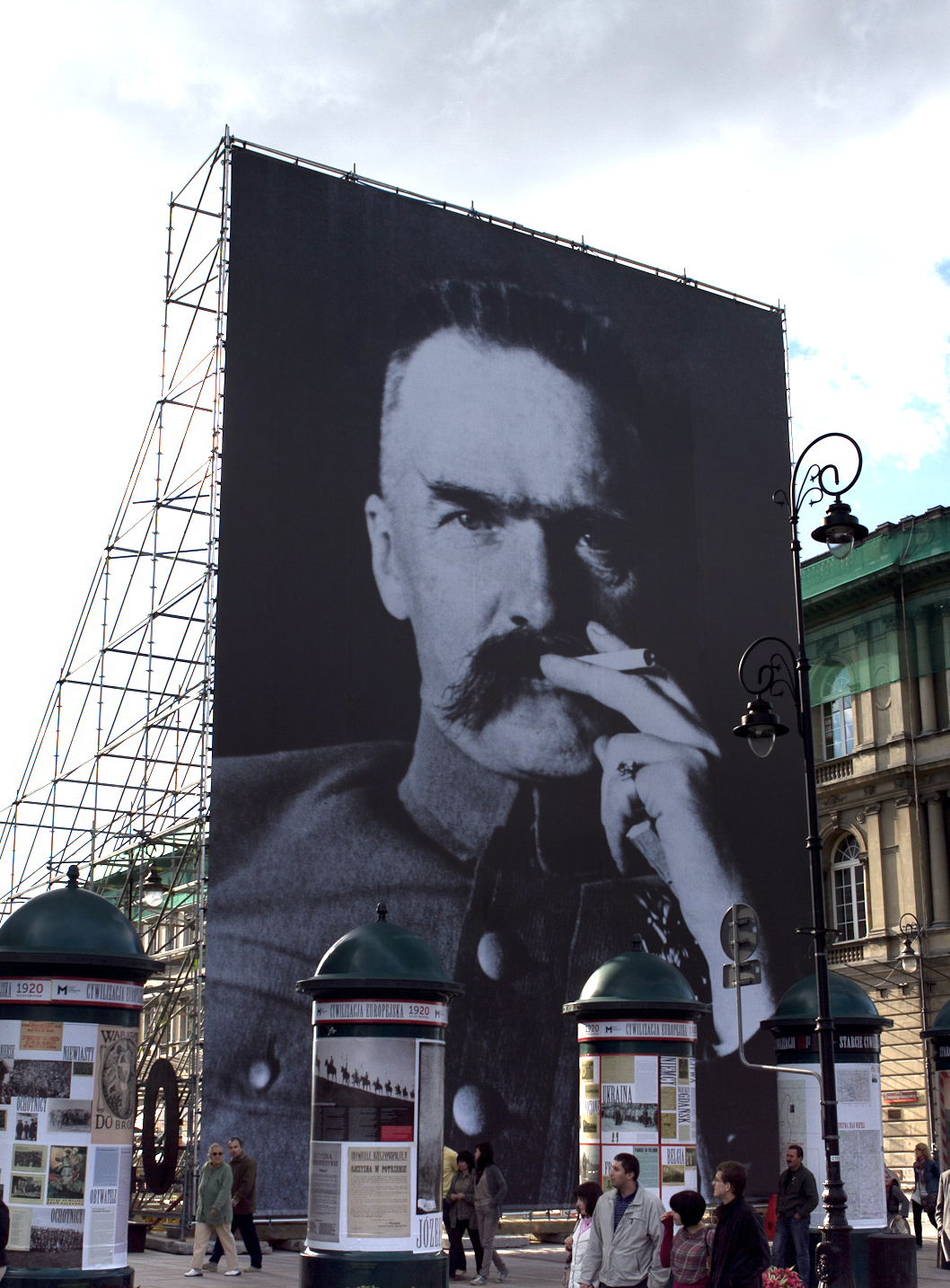

Banner of Józef Piłsudski in the streets of Warsaw (2010). Photo source: Flickr

The concepts of Intermarium and Prometheism were interconnected. The former enivsioned Poland as a power “from sea to sea” that would compete with Russia over dominance in Eastern Europe. The latter foresaw Russia breaking up, which would have had taken place as a result of uprisings of non-Russian nations living in the empire, and Poland would have led this. Both made references to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was idealised by Poles. Poland was seen as predisposed for a leadership position since its own Tatar minority could assist in the plight of the Russian Muslims who, at that time, were among the largest Muslim communities in the world.

Piłsudski’s support for Intermarium and Prometheism was a reflection of his biography. His family came from Lithuania’s most Lithuanian region: Samogitia. However, born north of Vilnius, he was, since childhood, surrounded by Belarusians, Lithuanians, Jews and Tatars. His cousin became the wife of Antanas Smetona, the father of independent Lithuania. In the 1890s, when the first country gathering of the Polish Socialist Party took place in a forest near Vilnius, among its five attendees were two Tatars. One of them was Aleksander Sulkiewicz – Piłsudski’s friend and the party’s general secretary. It is not surprising then, when looking at Piłsudski’s support from the time they were implementing Poland’s foreign policy between 1918 and1921, that some were more connected with the East because they were born and raised in Russia, Siberia, the Caucasus or even Central Asia.

Shortly after gaining independence, Poland suggested to Belarus, Lithuania and even Latvia a ‘reconstruction’ of the Great Lithuanian Duchy. In other words, it offered to rebuild a republic composed of three components (Vilnius-area Polish, Lithuanian and Belarusian). If Latvia was to be included, it could have been a four-part union. These republics would then become part of a federation with Poland.

The Polish political elite hoped that the main factor in favour of co-operation of these nations would be the Bolshevik threat. In April 1919, when Polish troops freed Vilnius from Bolshevik hands, Piłsudski issued a call in both Polish and Lithuanian, ‘To the inhabitants of the former Great Lithuanian Duchy’. After the takeover of Minsk, calls were also issued in Belarusian. In these appeals Piłsudski wrote the following: ‘The Polish troops, which I have brought here to expel the rule of force and violence, to abolish the ruling of a state against the will of the people – these troops are bringing you liberation and freedom. I want to provide you with a chance to solve domestic problems, ethnic problems and religious problems, in the fashion that you want to solve them, without any force or coercion on behalf of Poland.’

The Lithuanians, however, did not agree with the idea of a federation, seeing it as a threat leading to their Polonization. Thus when Poland was at war with Lithuania over Vilnius (1919-1920) and the Polish offensive was progressing into Lithuanian lands, the war from the point of view of Lithuanians turned into a fight for Lithuania’s independence. After the war, in 1920-1922, Poland tried to force Lithuania into a federation by creating an internationally unrecognised state called Central Lithuania (Litwa Środkowa) where Poles were the majority. Finally, Poland annexed Central Lithuania.

The Polish appeal to Belarusians ended with a bit better result; however, the national movement in Belarus was much weaker than in Lithuania or Ukraine. Thus, a part of the Belarusian political elite supported a federation with Poland. To achieve its goals, Poland began creating military units with Belarusians who supported a federation. Other Belarusians allied with Lithuania while others supported the Bolsheviks. Interestingly, Lithuanians and the Bolsheviks wanted a federation deriving from the tradition of the Great Lithuanian Duchy.

Poland had greater success with the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR), led by ataman Symon Petliura – despite the war for Eastern Galicia in 1918-1919. In fact, a few Poles held key positions in the administration and army of the UNR. In April 1920 Poland and Ukraine concluded an alliance and began an offensive which led to taking Kyiv from the Bolsheviks for a short time. The Bolsheviks countered by moving deeper into Ukrainian and Polish territory. By the time the Bolsheviks approached Warsaw in August 1920, where they failed significantly, the Polish army had around 30,000 Ukrainian soldiers among its ranks – nearly ten per cent of its total field forces. No other country but Ukraine supported Poland’s independence to such an extent at this difficult time. Unfortunately, there is not enough recognition of this fact today.

For Intermarium, Poland’s relations with Lithuania were crucial; partly because the Polish-Lithuanian alliance would have provided clear proof of Warsaw’s ability to co-operate with the Baltic states and the newly independent countries of Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, the survival of these states was perceived as a precondition for the strengthening of Polish independence. As Tadeusz Hołówka, a Polish diplomat and politician of the time, presciently said: ‘Poland’s independence cannot be imagined without the independence of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Ukraine and Belarus. Poland’s independence is one of the displays of a deep process which is today taking place in Europe; that is the liberation of nations from political imprisonment. If Poland is left alone, if other states that emerged from Russia’s collapse do not succeed, then we will have a sad future ahead of us.’

Even more ambitious was the idea of regional integration promoted by Włodzimierz Wakar, a distinguished commentator who saw a threat to Poland’s independence not only from Russia but from Germany. In his essay titled ‘The Jagiellonian idea in our times’, he claimed that Intermarium would lead to ‘the creation of a huge union of liberated nations between Germany and Russia, which would prevent them from future conquests. As a result, they would become tamed for centuries, would need to moderate their greed, and a just peace would rule over the nations; from us the Russians and Germans will finally learn to lead an honest national life. This is a significant goal that is worth working towards.’ Wakar assumed that a ‘Polish politics that are honest, just and free from “secrets and tricks” will encourage the newly independent states, starting with Latvia, all the way to Yugoslavia and Greece, to unite’. Clearly for Wakar, Intermarium was the biggest guarantee of Poland’s independence, which since the 18th century had been threatened by the presence of Germany (before Prussia) and Russia.

Soon after gaining independence, Poland proposed the establishment of a Baltic Union, whichwas to be composed of Poland, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania and Latvia. Poland also played a very important role during conferences with these states that were also often attended by representatives of Ukraine and Belarus. For example, during a conference in Bulduria (near Riga) in August 1920, soon after Poland’s victory at the battle over Warsaw, a pact was signed. It stipulated that the Baltic states would be solving “disputes between themselves by peaceful means and not make any pacts against each other, not tolerate any activities directed against any of the agreeing parties on their territories, guarantee the freedom of ethnic minorities and together conclude a defensive military convention”. However, this pact did not come into effect. It was hindered by the Polish-Lithuanian conflict over Vilnius.

Yet Poland pursued initiatives that went beyond diplomatic ones. It established military co-operation with Estonia, Finland and, especially, Latvia. In early 1920 Polish and Latvian troops liberated Latgale (a south eastern part of Latvia inhabited by a large Polish minority) from Bolshevik control. This region became part of Latvia.

The most ambitious idea in interwar Poland’s foreign policy was the attempt to put Prometheism into force. The biggest asset in this regard were the Polish-Lithuanian Tatars –recognized in the 19th century by their Turkic relatives as a source of inspiration for the processes of modernization and nation-building. This shows that the concept of Prometheism included a notion of freedom that was also closely connected to the programme of social modernization and the building of modern national identities. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Tatars of the former Great Lithuanian Duchy took up key positions in the government of the autonomous Crimea.

Moreover, in 1920 the Crimean government in exile approached the League of Nations to establish a Polish protectorate in Crimea. After the Bolshevik takeover of Crimea, Lithuanian Tatars moved to Azerbaijan, which was the first secular democratic republic that legally recognised the equality of men and women. Crimea’s former prime minister, Maciej Sulkiewicz (Suleyman bey Sulkiewicz), became the head of the military force, and established Azerbaijan’s army from scratch. However, he was murdered in 1920 after the Bolshevik’s takeover of Azerbaijan.

Looking at Poland’s relations with the Caucasus states during the interwar period, it is worth remembering that many representatives of their elite studied in Poland, while many Poles moved to Tbilisi or Baku for employment. While settling there, they had a huge impact on the development of both cities. Not surprisingly the father of Azerbaijan’s independence, Mahmud Rasulzade, had a private Polish teacher, while his Georgian counterpart, Noe Zhordania, became a socialist during his studies in Warsaw, where he established contacts with future builders of independent Poland. Therefore, it should not be difficult to understand why in 1918 the parliament of the Federation of Southern Caucasus changed its name into the Polish ‘Sejm’.

In the spring of 1920 Poland sent a large delegation to Georgia and Azerbaijan. In Tbilisi, Polish diplomats proposed a military alliance. It included plans of shared support to start an anti-Bolshevik uprising among Muslim mountaineers in the Northern Caucasus. However, during the visit of the Polish delegation in Baku, a Bolshevik invasion occurred, and the Polish diplomats were arrested.

Poland also established co-operation with Don, Kuban and Terek Cossacks who lived in the vicinity of the Caucasus. After the Bolshevik revolution, they also came up with the idea of building a common state that they would share with Muslim mountaineers from the Northern Caucasus and Cossacks from Astrakhan, the Urals and Central Asia. Those aspirations were partially linked with the emerging idea that Cossacks as a nation should separate from Russia. Even though no independent federation of Cossacks and Northern Caucasus emerged, Cossack military units were created in Poland in 1920. Together with Polish and Ukrainian troops, they fought against the Bolsheviks. There were also plans to create a unit of Caucasus mountaineers to fight with the Cossacks in the Polish military forces.

The apogee of Polish Prometheism was Poland’s support for socialist, non-communist and non-monarchist political forces inside Russia. In 1920 Piłsudski established co-operation with Boris Savinkov, a socialist revolutionary with Russian-Ukrainian roots. As a result, a Russian Army that was to fight against the Bolsheviks was set up in Poland. Even though it did not manage to join the fight before the signing of the Polish-Bolshevik truce (rozejm) in October 1920, Poland did manage to train around 6,000 soldiers.

Between 1918 and 1921 Poland defended its independence and became the largest state that emerged after the First World War in Europe. The Riga Peace Treaty, signed in March 1921by Poland and the Soviet Union, marked a failure in Poland’s attempts to build the Polish-Lithuanian federation which was to be strictly linked with Ukraine, promote the liberation of all non-Russian nations and build an Intermarium. The Peace of Riga meant that Poland withdrew its support for an independent Belarus and Ukraine. Their delegations were not allowed to participate in the negotiations in Riga. In turn, Warsaw recognised the new Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine, created by the Bolsheviks. In fact, both countries were divided between Poland and Bolshevik Russia. This situation was perceived by many Ukrainian and Belarusian politicians as a betrayal. It was the policy promoted by the National Democrats led by Roman Dmowski. At this time, they became the most popular political force in Poland.

As a result, Piłsudski could only say the following to his Ukrainian soldiers: ‘I am sorry, gentlemen. This is not how things were meant to be.’ It turned out that history, contrary to Piłsudski’s convictions, was more of a burden than an advantage in Poland’s relations with its eastern neighbours. Since the beginning of Poland’s independence, Lithuania refused any kind of a union with Poland. At the same time, Poland’s harsh policies towards Lithuania, which included an attempted coup d’etat and an attack on ethnic Lithuanian lands, raised concern among the small Baltic states regarding Warsaw’s intent. Quite often they interpreted Intermarium and the federation as an expression of Poland’s imperial aspirations and an attempt to impose its dominance over them. Russia succeeded at concluding separate peace treaties with all of the Baltic states, including a de facto alliance with Lithuania, undermining regional solidarity.

Belarusian and Ukrainian peasants, who were a decisive majority of inhabitants in Eastern Europe, were unwilling to accept the presence of Polish military forces and a provisional civil administration on their lands. The Polish army clearly supported Polish aristocracy, which had large land holdings and disregarded the non-Polish population in the administration. This situation made it very difficult to break the unwillingness of the Ukrainian and Belarusian peasants towards the idea of a federation with Poland. Piłsudski and people from his inner circle were concerned about this situation but they were incapable of overcoming the strong opposition of Dmowski’s National Democrats.

As stated above, the establishment of a Polish-Lithuanian federation in an alliance with an independent Ukraine was the basic condition for implementing the concept of Prometheism. That is why the failure of the former did not allow for the success of the latter. Despite that fiasco, Piłsudski’s policies had important long-term positive consequences. Without the Polish victory in the war for independence, probably the entire Central Europe might have been conquered much earlier by the Soviets. The Treaty of Riga together with the Treaty of Versailles established an international order in Europe which allowed several nations (Poles, Baltic countries, Finns, part of Ukrainians, etc.) to remain outside Soviet rule for almost 20 years. This situation contributed significantly to the strengthening of their national identities. Thanks to that strength they were able to survive Soviet aggression or domination. Today it helps them to counter the neo-imperial policy of Russia.

As stated by the Polish historian Jerzy Borzęcki: ‘Even though Polish federalism was not the most popular, it forced Moscow to activities that were aimed at maintaining the illusion of Belarusian and Ukrainian independence. As a result, it contributed to the establishment of the Soviet Union as a federation of republics, which included two most important ones, apart from Russia – Belarus and Ukraine.

It is worth noting that in 1922 the Soviet Union added one more republic: the Transcaucasian Soviet Socialist Republic (which was made up of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan). The federal nature of the Soviet Union, though often only nominally, was different from the centralised system of Tsarist Russia. And in 1991, after the collapse of the USSR, it became the foundation for the creation of over a dozen newly independent states.

Published 7 January 2019

Original in English

Translated by

Iwona Reichardt

First published by New Eastern Europe 2018 Winter

Contributed by New Eastern Europe © Adam Balcer / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Expectations, standards, and requirements in higher education vary from country to country. In the third episode of the Knowledgeable Youth podcast Ukrainian students embark on the complex subject of tertiary education.

The crux of different peoples’ history, and of humanity as a whole, is always food and hunger. In the final analysis, it’s the stomach that counts.