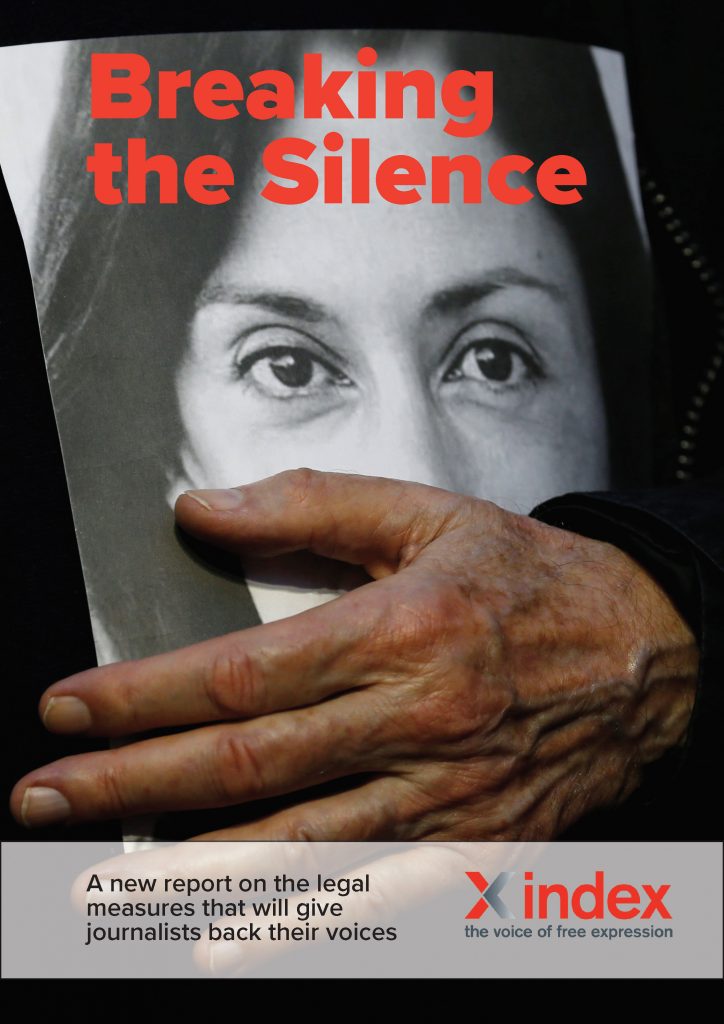

At the time of her assassination in 2017, Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was facing 47 civil and criminal defamation suits. After her death, about 30 of these were transferred to her family under a Maltese law that allows claimants to pursue actions against the heirs of a deceased defendant.

Caruana Galizia is among the most well-known targets in Europe. Slapps – an acronym for strategic lawsuits against public participation – are a type of legal action not undertaken to be won but to intimidate defendants into silence or inaction. They are most often used by powerful actors (corporations, public officials, high-profile businesspeople) in an attempt to stop individuals or organisations from expressing critical views on issues of public interest. They imperil not only independent journalism but academia, activism and other forms of civic engagement. And they seem to be becoming more common around the world.

‘Free speech is vastly protected by the anti-Slapp statute – it’s a night and day difference,’ said California-based lawyer Thomas R Burke about a law in the USA that protects people from being vexatiously sued for exercising their right to free speech. Burke was speaking at a roundtable event organised by Index in July. He was one of 15 legal practitioners and academics to have participated in a virtual discussion which forms the basis for ‘Breaking the Silence’, a report published by Index that looks at the legal measures that will help give journalists back their voices. It is the second report from Index on Censorship’s ongoing research project into Slapps following a May report that looked in depth at the legal challenges journalists are facing in countries across Europe.

‘Even though we know that they will win, it still takes several years,’ said one participant regarding vexatious criminal lawsuits in Hungary. Slapps are usually based on defamation laws and can take the form of criminal lawsuits when national laws permit. Lengthy litigation is characteristic of Slapp lawsuits, with plaintiffs typically looking to drain defendants of as much time and money as possible in an effort to punish them and discourage any further scrutiny. Excessively strict defamation laws and lengthy judicial procedures are just two of the issues that are amplifying the impact of Slapps, according to ‘Breaking the Silence’.

‘Breaking the Silence’. A report by Index on Censorship on strategic lawsuits against public participation (slapps).

Lawyers in Hungary, Poland and Northern Ireland have expressed concern over the increasing misuse of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation and privacy laws. According to the new report, police in the Polish city of Olsztyn issued a statement earlier this year saying that publishing videos of police interventions online ‘may give rise to liability for violation of the provisions on the protection of personal data’. Poland’s commissioner for human rights condemned the misleading statement and called on Olsztyn police to amend it, referring to the GDPR’s journalistic exemption, which also applies to citizen journalists.

‘Breaking the Silence’ also puts forward some potential recommendations that could impede the effectiveness of Slapps, as discussed by the legal experts who attended the roundtable. One of the most far-reaching measures is the introduction of anti-Slapp legislation, such as an EU anti-Slapp directive. Věra Jourov, the EU commissioner for values and transparency, has indicated that she is in favour of this. In June, she replied to MEPs who had written to her about this saying she would look at ‘all possible options to address this matter’.

The right to privacy is protected under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, and freedom of expression may be subject to restrictions if anyone’s privacy is unlawfully interfered with. Legislation would need to respect individuals’ rights to bring legitimate action against any violation of these rights, while also offering increased protection to journalists, activists and others who speak out on matters of public interest.

What could such legislation look like? Breaking the Silence includes the insights of Burke, who has successfully litigated hundreds of anti-Slapp cases in California – a state that has had an anti-Slapp statute in place since 1992. According to Burke, the statute enables a defendant to file a motion to dismiss complaints through a quick judgment-like procedure. Once the motion is filed, amendments cannot be made to the complaint and the plaintiff cannot dismiss it without facing legal fees. The motion also places a freeze on discovery (pre-trial exchange of evidence), the most expensive stage of litigation in the USA. If the motion is granted, the action is dismissed and the defendant recovers all costs.

‘It would be enormously effective, but how do we do that now when we have politicians banging on about fake news?’ replied one of the European lawyers upon hearing of the legislation. As ‘Breaking the Silence’ shows, several legal experts expressed concern about the prospect of introducing such legislation amid the current political environment. ‘Politicians are very reluctant at the moment to give additional protections to online media and social media. There’s rather a tendency to restrict and repress,’ noted one legal expert.

As efforts continue among a coalition of civil society organisations – which includes Index on Censorship – to push for an EU anti-Slapp directive, other measures can be put in place to help support Slapp victims. ‘Breaking the Silence’ proposes training for judges and journalists, a rethink of the role of the jury in media trials, and the full application of European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case law.

Norway, which has comparatively few Slapp cases, is mentioned as an example. ‘In the 1980s and 1990s, defamation cases were a problem – a big problem – for the Norwegian press because we had not properly incorporated the jurisprudence of the European Court,’ explained one Norwegian lawyer. Now Norwegian courts allow for defences provided for by ECtHR jurisprudence to be used. ‘It doesn’t mean the media don’t lose cases,’ he said, ‘but it’s a much more realistic attitude toward press freedom.’

According to ‘Breaking the Silence’, another reason why Norway has been so successful in protecting its media against Slapps is the well-organised nature of its editors’ and press associations. This contrasts with Italy, where the media – and freelance journalists in particular – are habitually targeted with Slapps. According to Italian lawyer Andrea di Pietro, who spoke to Index, ‘journalists are really economically isolated, also from a trade union perspective; therefore, weakening journalists with a lawsuit is very possible thanks to a legal system that doesn’t punish [the vexatious litigators]’.

The implementation of the recommendations in ‘Breaking the Silence’ will be key to protecting freedom of expression and democracy. But some recommendations – not least the introduction of anti-Slapp legislation – will take time to bring about. In the meantime, civil society and the media must come together to ensure that journalists are supported and are not silenced by these abusive legal threats and actions.

This article was first published in Index on Censorship. Read more here.