Disillusion with social media only stimulates the search for ever more refined techniques of manipulation. Detoxing won’t help, writes Geert Lovink: it is collective action, not will power, that can free us from the permanent state of distraction.

‘Never get high on your own supply.’ (Ten Crack Commandments) – ‘The Other as Distraction: Sartre on Mindfulness’ (Open University lecture) – ‘She never felt like she belonged anywhere, except for when she was lying on her bed, pretending to be somewhere else.’ (Rainbow Rowell) – ‘This content is not suitable for all advertisers.’ – ‘In my head I do everything right.’ (Lorde) – ‘15 years ago, the internet was an escape from the real world. Now, the real world is an escape from the internet.’ (Noah Smith) – ‘Do Not Feed the Platforms.’ (t-shirt) – ‘My words don’t matter and I don’t matter, but everyone should listen to me anyway.’ (Pinterest) – ‘Stop Liking, Start Licking.’ (ice cream advertisement) – #ThisIsWhatAnxietyFeelsLike – ‘Kick that habit, man.’ (W. Burroughs).

Welcome to the New Normal. Social media is reformatting our interior lives. As platform and individual become inseparable, social networking becomes identical with the ‘social’ itself. No longer curious what ‘the next web’ will bring, we chat about what sort of information we’re allowed to graze over during lean periods. Former confidence in the seasonality of hypes has been shattered. Instead, a new realism has set in. As Evgeny Morozov put it in a tweet: ‘1990s tech utopianism posited that networks weaken or replace hierarchies. In reality, networks amplify hierarchies and make them less visible.’1

An amoral stand towards today’s intense social media usage would be to not pass judgement and instead to delve into the shallow time of lost souls like us. How can one write a phenomenology of asynchronous connections and their cultural effects, formulate a critique of everything hardwired into the social body of the network, while not looking at what’s going on inside? Let’s therefore embark on a journey into this third space called the techno-social.

Networks are not quite pleasure domes. Discontent grows around form and cause: from Russia’s alleged interference in the 2016 US presidential elections, to former Facebook president Sean Parker admitting that the site employs ‘addiction by design’. Parker: ‘It’s a social-validation feedback loop … exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.’2 Next is Justin Rosenstein, inventor of the Facebook ‘like’ button, who compares Snapchat with heroin. Or Leah Pearlman, a former Facebook project manager, admitting that she too has grown disaffected with the ‘like’ button and similar addictive feedback loops.3 Or Chamath Palihapitiya, another former Facebook executive, who claims that social media is tearing society apart and advises people to ‘take a hard break’.4

After reading such stories, who wouldn’t feel betrayed? Cynical reason sets in as we realize the tricks being played on us. The screens are not what they seem. Behavioural targeting is exposed and our suspicions are confirmed; the effects wear off and marketing departments go on the look-out for the next form of perception management. Is it never going to end? What does our awareness of ‘organized distraction’ mean? We know we’re being interrupted yet continue to let it happen: that’s distraction 2.0.

What to do once we realize we are cornered and must come to terms with mental submission? What is the role of critique and of alternatives in such a desperate situation of ubiquity? Depression is a general condition, whether realized or unrealized. The internet – is that all there is? Discontent with the cultural matrix of the twenty-first century necessarily moves from ‘technology’ to political economy. Let’s see our collective inability to change the architecture of the internet in terms of ‘democracy fatigue’ and the rise of populist authoritarianism and the ‘Great Regression’.5

But let’s also beware of moralism passing for critical analysis. We must confront the uncomfortable question as to why so many have been lured into the social media abyss in the first place. Is it perhaps because of the ‘disorganization of the will’ that Eva Illouz talks about in her book Why Love Hurts?6 Those that defend the usefulness of Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram at the same time express mixed feelings about Mark Zuckerberg’s moral policing. In what Illouz describes as ‘cool ambivalence’, rational and emotional considerations blur, causing a crisis of commitment – a pattern we also see in the social media debate. I want to leave but I can’t. There’s too much but it’s boring. It’s useful yet disgusting. If we dare to admit it, our addictions are filled with an emptiness at the prospect of a life unplugged from the stream.

Dopamine is the metaphor of our age. The neurotransmitter stands for the accelerated up-cycles in our mood, before we come crashing down. The flux on social media varies from outbursts of expectation to long periods of numbness. Social mobility is marked by similar swings. Good and bad fortune stumble across each other. Life goes its way, until you suddenly find yourself in an ‘extortion’ trap, your device hijacked by ransomware. We move from intense experiences of collective work satisfaction, if we are lucky, to long periods of job uncertainty, filled with boredom. Our interconnected life is a story of growth spurts followed by stagnation, when staying connected no longer serves a purpose. Let’s call it social hoovering: we’re sucked back in, enticed by improvements that never materialize.

Social media architectures lock us in, legitimated by the network effect. Everyone is in on it, at least so we assume. The certainty, still felt a decade ago, that users behave like swarms, moving together from one platform to the next, has been proven wrong. Departure seems persistently futile. We have to know the whereabouts of our ex, the event calendars and social conflicts of old or new tribes. One can unfriend, unsubscribe, log off or block individual harassers, but the tricks that get you back into the system ultimately prevail. Blocking and deleting is considered an act of self-love. The idea of leaving social media altogether is beyond our imagination.

Our unease with ‘the social’ starts to hurt. Lately, life seems overwhelming. We go silent yet return before long. The fact that there’s no exit or escape leads to anxiety, burn-out and depression. Hans Schnitzler reports on the liberating withdrawal symptoms experienced by his students when they discover the magic experience of walking through the park without having to take Instagram snapshots.7 At the same time, we hear growing aversion towards New Age ‘school of life’ responses to digital overload. Internet critics give voice to the outrage over the instrumental use of behavioural science, aimed at manipulating the user, only to see their concerns ending up as ‘digital detox’ recommendations in self-help courses. Nothing much happens after the Alcohol Anonymous-style confessions of MyDistraction.

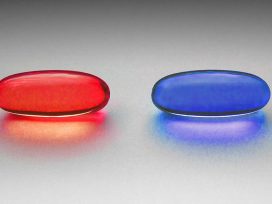

Should one be satisfied with a ten per cent reduction of time spent on devices? How long does it take until the effect has worn off? Are you also feeling restless? Well-meant advice becomes part of the problem, since it mirrors the avalanche of applications aimed to create ‘a better version of you’.8 Instead, we need to find ways to politicize the situation. A ‘platform capitalism’ approach must, first of all, avoid any solution based on the addiction metaphor: the online billions are not sick and I’m not a patient either.9 The problem is not our lack of will-power, but our collective inability to enforce change.

We face a return of the hi-lo distinction in society with an offline elite that has delegated its online presence to personal assistants, in contrast to the frantic 99% that can no longer survive without 24/7 access, struggling with long commutes, multiple jobs and social pressures, juggling complex sexual relationships, friends and relatives with noise on all channels.

Another regressive tendency is the ‘televisual turn’ of the Web experience, due to the rise of online video, the remediation of classic TV channels on internet devices and the emergence of services such as Netflix. A Reddit Shower Thought put it this way: ‘Surfing the web has become like watching TV back in the day, just flicking through a handful of websites looking for something new on.’10 Social media as the new TV is part of a long-term erosion of the once celebrated participatory culture, a move from interactivity to interpassivity.11 This world is massive but empty. What’s left are the traces of the collective outrage of those that do comment. We read what the trolls have to say and swipe away the verbal filth in anger.

One of the unintended consequences of social media use is the growing reluctance to have direct verbal exchanges. In his blog-posting, ‘I hate telephones’, James Fisher complains about the dysfunctionality of call centres and labels all ‘synchronous’ telecommunication inefficient: ‘Asynchronous textual communication is how everyone communicates remotely now. It’s here to stay.’12 According to Fisher, killing the telephone is a big market. This is part of a silent revolution. The most effective way to sabotage the medium is to not take calls anymore. During a visit to a vocational media college in Amsterdam, I was told that the school had introduced a ‘communication’ class for digital natives after firms had complained that interns were incapable of talking to clients on the phone.

Dialogue, whether on the phone or in a café, is an expansive semiotic landscape where meaning is not tied to commitment. Instead, it’s all about decision avoidance, probes into the world of the possible. We get lost in time while we ask, explain, interrupt and wonder, guessing the meaning of the hesitations and body language of our partner. This extensive experience is the opposite of the compression technique, manifested in the condensed form of the meme. These compress complex issues into a single image, adding an ironic layer, with the explicit aim of propagating a message that can be grasped in a split second, before being swiped away.

‘Please approach me, astonish me.’ No matter how perfect the technology, smooth and fast exchanges remain the exception when we bump into the harsh reality of the Other. At the moment we send a text message we expect to receive one back. This wait, also known as ‘textpectation’, can be a long and painful experience. ‘Every time my phone vibrates, I hope it’s you.’ As Roland Barthes noticed, ‘to make someone wait is the constant prerogative of all power.’13 It is always me that waits.

After the excitement, during the dark days, social media no longer fills the void. During the loveless days one feels flat, like a failure. Some get angry easily: social anxiety is on the rise. When mood stabilizers no longer work, and you no longer get dressed in the morning, you know you’ve been hoovered.

Swiping fingers help move the mind elsewhere. Checking the smartphone is the new daydreaming. Unaware of our brief absence, we enjoy the feeling of being remotely present. While checking status updates we wander off, the movement is reversed and, unannounced, the Other enters our world. Like day dreaming, social media visits can be described as ‘short-term detachment from one’s immediate surroundings during which a person’s contact with reality is blurred’.14

However, the second part of this Wikipedia definition doesn’t fit. Do we pretend to be somewhere else when we swipe through messages in the elevator? Quick social media scans may be an escape from present reality, but do we withdraw into a fantasy? Hardly. We glance through updates and incoming message for the same reason that we daydream: to erase boredom.

Should we see social media use as an expression of repressed instincts? Or instead read social media as flows of digital signs coming from dispersed tribe members? Does the psyche need to restore social ties in order to regain a sense of kinship in the age of thinly-spread networks? We re-assemble those close to us on our devices. Can we describe the online version of the social as a secondary revision (Freud), a form of processing the complex processes in our everyday lives?

Can we understand social media use in cafes, on the street, in trains, in the kitchen and in bed as an altered form of consciousness, this time fed by the outside world? Certainly, a definition of social media as ‘alertness of the elsewhere’ or even ‘techno-telepathy’ runs counter to widespread calls for more bodily and spiritual presence, leading to a less-distracted brain able to concentrate longer, and better.

Admit the envy: others have rewarding experiences from which you are absent. The Fear of Missing Out causes this constant desire for engagement with others and the world. Jealousy is the underside of the need to be part of the tribe, at the party, chest-to-chest. They are dancing and drinking while you’re outside, on your own. There is also another aspect: the online voyeurism, the cold, detached form of peer-to-peer surveillance that carefully avoids direct interaction. We watch and are being watched online.

Overwhelmed by a false sense of familiarity with the Other, we quickly get bored and restless. While still aware of our historical duty to contribute, upload and comment, the reality is different. We’ve regressed back to news outlets and professional influencers: only a few know how to turn attention to their advantage.

When applications are no longer new, they turn into a habit. This is the moment when geeks, activists and artists vanish from the scene and are replaced by parents, psychologists, data analysts and marketing experts. In Updating to Remain the Same, Wendy Chun argues that ‘media matter most when they seem not to matter at all, that is, when they have moved from the new to the habitual’.15 Chun describes habits as strange, contradictory things, both inflexible and creative. Habit enables stability in a universe in which change is fundamental. Its repetitive nature is not seen as something bad. ‘Habit, unlike instinct, is learned, cultivated: it is evidence of culture in the strongest of the world.’16 Its policy of privatization destroys the private sphere, resulting in internet users being turned inside out, framed as private subjects exposed in public.

‘Habitual media’ capitalize on the wish for anti-experience, sharing information within one’s own filter bubble. Decoupled from its radically Other newness factor, social media caters to the desire for something different. This also plays out on the interpersonal level. ‘Experience becomes piercing, grating, intrusive,’ observes Mark Greif. ‘It is no longer a prize, though it is the goal everyone else seeks. It is a scourge. All you wish for is some means to reduce the feeling.’17

We start to feel detached as friends get emotionally over-demanding. Once we no longer care, and the melodrama is gone, we give it a glance, like it and a split second later swipe on. Social anxiety wears off and flattens out into a mood of indifference, in which the world still glides, but with a quality of numbness. When the world is emptied of meaning, we’re more than ready to delegate experiences to friends. No hard feelings. As distance grows, jealousy dissipates.

In order to investigate the term ‘social cooling’, technology critic Tijmen Schep has created a website that tries to capture the long-term effects of living inside a reputation economy. Cooling describes the simple observation that if you are being watched, you change your behaviour. ‘People are starting to realize that their “digital reputation” could limit their opportunities.’18 This leads to a culture of conformity, risk aversion and social rigidity. Resistance will have to seek to decommission algorithms and criminalize data gathering. Only when data analysis services are no longer available will there be a chance of collectively ‘forgetting’ these cultural techniques and their consequences.

Schep’s conclusion: ‘Data is not the new gold, it is the new oil, and it is damaging the social environment.’ A recent Data Prevention Manifesto argues along similar lines: it’s not enough to ‘protect privacy’ through regulation. Both data production and capture need to be prevented in the first place. For Schep, privacy means the right to be imperfect. We need to design a freedom that undermines the technological pressures to lead a predictable life. Otherwise, we might find ourselves living under a regime of social credit. Welcome to Minority Report Society, in which deviancy prevention has been internalized.

Remember the film Her? In it, the male mid-life crisis character falls in love with a female operating system called Samantha. The film is a both a parable about narcissistic solitude and a ‘soulful’ story about machines that assist us in the difficult passage from one relationship to the next. In Her’s retro-future scenario, we’ve conformed to a uniform life and shied away from diversity. But we can’t say the subjects of Her are absent-minded. The ‘artificial interiority’ they inhabit, being structurally inattentive to outer things, shields off contact with the outside, much like the innocent Hello Kitty dresses visible on the streets of metropolitan Asia for decades.

In her book Distributed Attention, media theorist Petra Loeffler provides us with a shift of perspective.19 Going back to the writings of Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Krakauer, she notes that distraction was once seen as a right claimed by the early labour movement. Repetitive factory work had to be compensated with entertainment. The demand for leisure time was supported by technologies such as the panorama, the world exhibition, the kaleidoscope, stereoscope and cinema, a metropolitan culture embodied in the figure of the gawker.

With the rise of media technologies after World War II, this attitude slowly changed. The phase of ‘disorientation’ (Bernard Stiegler) set in. Now that we’ve detached distraction from entertainment, we are no longer able to see how the smart phone is a necessary toy in the reproduction of the labour force.20 At what cost? Instead of policing digital daydreaming, we should bet on the horse called boredom. At some point, Silicon Valley will lose its war on attention and its add-driven economy will make the inevitable slide. But we’re not there yet. Their strategies of behavioural fine-tuning and surprise still work.

Loeffler’s historicization can help us to free ourselves from the morals that surround the distraction discourse and to ask what exactly it is that is pulling us deeper and deeper into these networks. As Roland Barthes did with photography, let’s investigate the ‘punctum’ of social media. How can you identify and analyse the striking element that hurts and attracts you, that rare detail your eye is searching for? It is the possibility of freedom and liberation from orchestrated stimulation, the unlikely information that will upset the routine. What we desire is the next wave of disruptions, while feeling unable to disrupt our own behaviour. Addiction ‘programs its continued use by blocking our ability to envisage alternatives’ (Gerald Moore). We’re locked into a situation that makes it impossible to ‘disrupt the disruptors’.

As the discontent with the distraction discourse spreads, there’s a growing revolt against the suggestion that it’s all our own problem. Take Catherine Labiran, who no longer wants self-care to be synonymous with pampering, recognizing that she ‘grew tired of conversations about self-care being solely linked to some form of meditation’.21 Digital detox therapy only fights the symptoms, writes Miriam Rasch: ‘It overlooks the causes of perpetual distraction, loss of concentration and burn-outs. Going out into the woods without a phone will not help you in the long run.’22 According to Rasch, detoxing and other disciplinary strategies only help corporations make more money.

Michael Dieter disagrees. He warns that it’s too easy to condemn digital detox retreats as a neoliberal ruse. ‘The retreat highlights a need for collective practices and changing the environment of use,’ he argues. ‘I’m not sure we should trust our individual interests to fight distraction alone … Pure detox is a risky endeavour, as medical experts claim: it can strengthen the impulses or habits that we aim to get rid of. Hybrid media experiences, diversified interdisciplinary forms of training and more-than-digital methods are some paths forward, along with a willingness to experience crisis as moments of clarity.’23

The elite is in two minds about the ‘distraction epidemic’, a confusion with profound implications for educational standards and pedagogic approaches. The rulers demand digital skills sets and deep reading abilities at the same time. It is not in their interest to bring the hollow user to life. We’re not just talking about doubts rationalized as ethical issues; the attention issue goes to the core of how the global economy is being shaped. On the one hand, research repeatedly makes the point that considerable productivity gains will be made once access to social media during work hours is prevented. On the other hand, a growing number of businesses benefit precisely from the blurring of boundaries between work and private life. Under employment conditions that make permanent access a prerequisite, going offline is a potentially dangerous affair. The app that hooks us, will also set us free.

Should the response to the ‘access for all’ demand be the ‘right to disconnection’? Can we move beyond this dichotomy?24 Existing social media lack hubris, style and enigma. It’s their petty, sleazy, behind-our-backs mentality that needs to be attacked. In order to avoid offline romanticism, we need to ask what information is really vital for us, how we can obtain it regardless, and to what extent we can accept built-in delays. Can vital information bridge the ‘air-gap’ and reach us even when we’re no longer present on the networks? Offline or online, what counts is how we escape from a calculated life, together. It was fun while it lasted, but now we’re moving on.

A German translation of this article was published in Lettre Internationale 120 (2018); a longer English version is published on the author’s blog Net Critique. A Spanish translation can also be read here.

Twitter, July 11, 2017.

Heinrich Geiselberger, The Great Regression, Cambridge, 2017. The term ‘democracy fatigue’ is the title of the opening essay by Arjun Appadurai.

Eva Illouz, Why Love Hurts, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2012, 90.

Hans Schnitzler. Kleine filosofie van de digitale onthouding, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2017.

Title of a ‘technology fair’ in Seoul: http://www.artsonje.org/en/abetterversionofyou/.

An example from the arts world would be the London exhibit at Furtherfield, We’re All Addicts Now: https://www.furtherfield.org/events/are-we-all-addicts-now/.

I am using interpassivity here in a media technological sense and slightly differently from Robert Pfaller, who defines the term as ‘delegated enjoyment’ and ‘flight from pleasure’. See: Robert Pfaller, On the Pleasure Principle in Culture, London/New York 2014, 18.

Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, London 1990, 87.

Wendy Chun, Updating to Remain the Same, Cambridge (Mass.) 2017, 1.

Ibid. 6.

Mark Greif, Against Everything, London/New York, 2016, 225.

Petra Löffler, Verteilte Aufmerksamkeit: Eine Mediengeschichte der Zerstreuung, Zürich-Berlin 2014.

Rob Horning, ‘Distraction is no longer a relief from tedium but its metronome.’ See: https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/ordinary-boredom/.

Email exchange with Miriam Rasch, November 2017.

Email exchange with Michael Dieter, December 2017.

See interview with Pepita Hesselberth: http://blogs.cim.warwick.ac.uk/outofdata/2017/06/01/on-disconnection/.

Published 28 March 2018

Original in English

First published by Lettre International 120 (2018) (German version); Eurozine (English version)

© Geert Lovink / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Planetary imagination

Soundings 78 (2021)

In ‘Soundings’: environmental justice and the failure of neoliberal regulation; littered space and the emergency in Low Earth Orbit; Dipesh Chakrabarty on the global of global warming; and Paul Gilroy on the creolized planet.

COP26’s mandate focuses on averting the loss and damage caused by climate change. And technological solutions hold much promise. But high-tech and the environment aren’t always best matched: largely unregulated mega satellite projects are on the increase with space debris a real near-space threat.