Even though socialist internationalism was the official ideology in communist Hungary, popular media at the time was teaming with nationalist narratives, hidden in plain sight. What does this contradiction explain about today’s politics?

Is the return of Serbian nationalism to be dismissed as domestic political point-scoring in an election year, or does it pose a deeper threat to the region? And will Russia step in as the rift with the EU over Kosovo deepens? Slavenka Drakulic considers the possibilities.

A long time ago, in a far away land, a Great Leader told his people, who were as poor as church mice: “We will eat grass rather than give in!” The land was called Albania and it was the early Sixties. Enver Hoxha had broken off the alliance with the USSR and Nikita Khrushchev had stopped sending aid, including grain. Albania then turned towards… China. Ever since, “eating grass” has been a proverbial expression for a stubborn kind of pride, and also for the willingness of an authoritarian regime to sacrifice people’s wellbeing in the name of “principles” – be it isolationism, Marxism or nationalism.

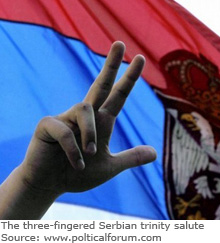

It looks as if Serbia might be on its way to tasting grass right now. During a recent visit to the medieval Orthodox monastery Decani, which is situated in the Republic of Kosovo, the Serbian President Boris Tadic said that Serbia would never recognized Kosovo as an independent state. A few months previously, however, his attitude had been more conciliatory: Serbia does not recognize Kosovo, but is open for negotiations. Now, no negotiations were mentioned and Tadic’s “never” sounded like a pretty dramatic swing towards nationalism. For a long time, the EU had pinned its hopes on this educated, westernized politician, a sort rare in the Balkans. Now it looks like those hopes have been disappointed. The question is: why?

When nationalism becomes “in”, one can be sure that elections are approaching, be it in Serbia, Belgium, Hungary or Croatia. Before Croatia’s December 2011 parliamentary elections, the Croatian Democratic Party (HDZ), the country’s leading party, showed signs of reverting to Tudjmanism – an authoritarian, aggressive brand of nationalism that in the last decade has became pretty much passé. Instead of adopting the values of tolerance promoted by the EU, HDZ leader Jadranka Kosor adopted a populist, nationalist rhetoric in the belief that it would win over voters clinging to the old days.

When nationalism becomes “in”, one can be sure that elections are approaching, be it in Serbia, Belgium, Hungary or Croatia. Before Croatia’s December 2011 parliamentary elections, the Croatian Democratic Party (HDZ), the country’s leading party, showed signs of reverting to Tudjmanism – an authoritarian, aggressive brand of nationalism that in the last decade has became pretty much passé. Instead of adopting the values of tolerance promoted by the EU, HDZ leader Jadranka Kosor adopted a populist, nationalist rhetoric in the belief that it would win over voters clinging to the old days.

With Croatia on the threshold of becoming a member of the EU (the referendum on 22 January showed 66 per cent support), the nationalist agenda can be interpreted as the last resort of losers. But the nationalist rhetoric in Serbia should be taken more seriously. With parliamentary and presidential elections approaching this year, Tadic’s swing towards nationalism is a telling sign. Many Serbs do not accept Kosovo’s declaration of independence and consider it part of their state. According to the opinion pools, the ultra-nationalist Serbian Progressive Party headed by Tomo Nikolic is becoming more popular than Tadic’s Democratic Party. Tadic has to adapt his vocabulary to this situation. Despite Angela Merkel’s recent visit to Serbia and her urging of Tadic to compromise, the general mood of his country has forced him to back-peddle. Further talks between Brussels and Belgrade have now been postponed until the spring at the earliest.

It therefore looks as if nothing will change for the better in Serbia in the immediate future. If anything, nationalism could escalate. Moreover, the Kosovo question means that Serbia is drifting away from the EU. But Brussels cannot and will not cease to demand that Serbia recognize Kosovo’s independence. There are therefore two sides in this Balkan game, neither of which can make a move. Further aggravating the situation is the Union’s general unwillingness to consider new members, a result of the general crisis and growing nationalism within the EU.

Will this mean that Serbia remains isolated in Europe, like Albania once was? Will Serbs be forced to “eat grass”? Not quite. It would be different were Serbia dependent solely on the EU for “grain” and other goodies. But as communist Albania once connected herself with distant China, so Serbia is already well plugged-in with not-so-distant Russia. If the EU were to place too harsh demands on Belgrade – well, there are always the “fellow Slavs” who can ease Serbia’s suffering and add potatoes and even a little meat to their diet of grass. And Serbian grass, spiced up by Russia, would certainly taste better than the Albanian variety. There is a long tradition of sympathy and solidarity between the two peoples. During Soviet times, Serbs used to say, “Together with the Russians we make up 300 million”. But while there is no doubt that today’s Russia is a big power, it is also an ambitious one. Russia would not help Serbia out of charity. It wants to keep a foot in the door of central Europe. Seen from the West, the strong economic and political presence of Russia in a potential EU member country is not a pleasant scenario.

Slovenia is a member of the EU, Croatia is just about to enter it, Montenegro will soon start negotiating. Even Macedonia, suffering from the Greek ban of its name, has a better chance of a future membership than Serbia – as long as Belgrade is not prepared to solve the Kosovo problem. And what about Bosnia-Herzegovina? While it might be an independent state, it is not really a fully functioning one. A part of it, the so-called Republika Srpska, is all but formally independent. In reality, Bosnia is divided, functioning along nationalist divisions, supported – and ultimately ruled – by “the international community”, through its High Representative.

Even so many years after the end of the several wars there, the territory of the former Yugoslavia remains a potentially destabilizing region of Europe. On the other hand, nationalist rhetoric primarily serves domestic policy purposes. In Serbia, George Orwell’s “doublespeak” is alive and well. It flourished under both Tito and Milosevic – and it still does. “Never” doesn’t really have to be never.

Published 1 February 2012

Original in English

First published by Süddeutsche Zeitung 24.01.2012 (German version); Eurozine (English version)

© Slavenka Drakulic / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Even though socialist internationalism was the official ideology in communist Hungary, popular media at the time was teaming with nationalist narratives, hidden in plain sight. What does this contradiction explain about today’s politics?

Reintegrating Russian-speaking Ukrainians into the ‘Motherland’ – one of Putin’s central pretexts for war – has impacted a sharp counter reaction: many are abandoning their mother tongue, reaffirming their Ukrainian identity. Could Ukraine be headed for monolingualism after centuries of multi-language cultural exchange?