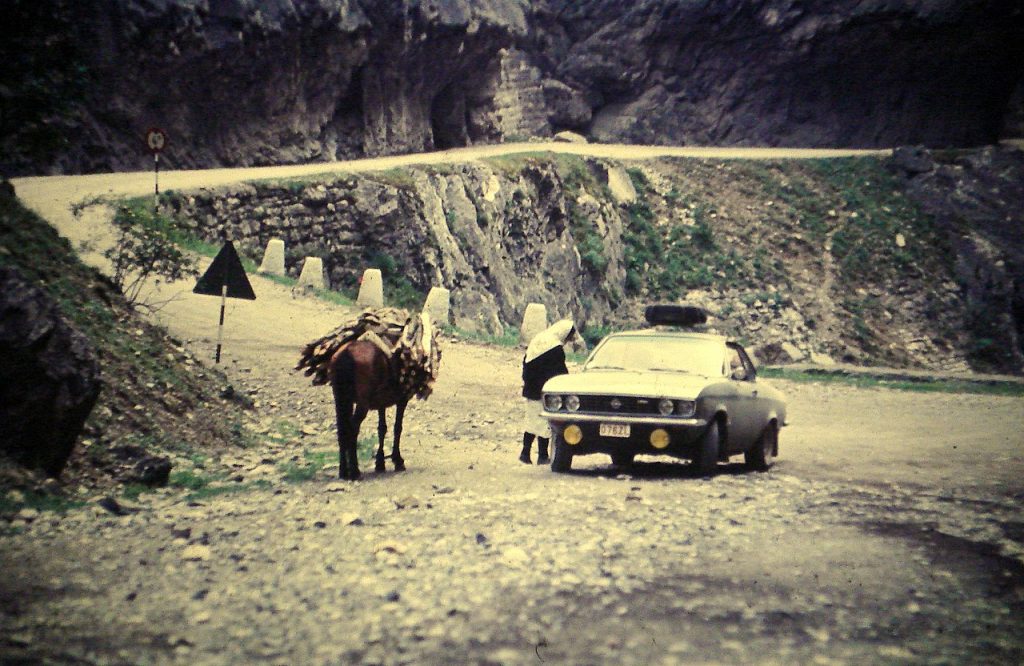

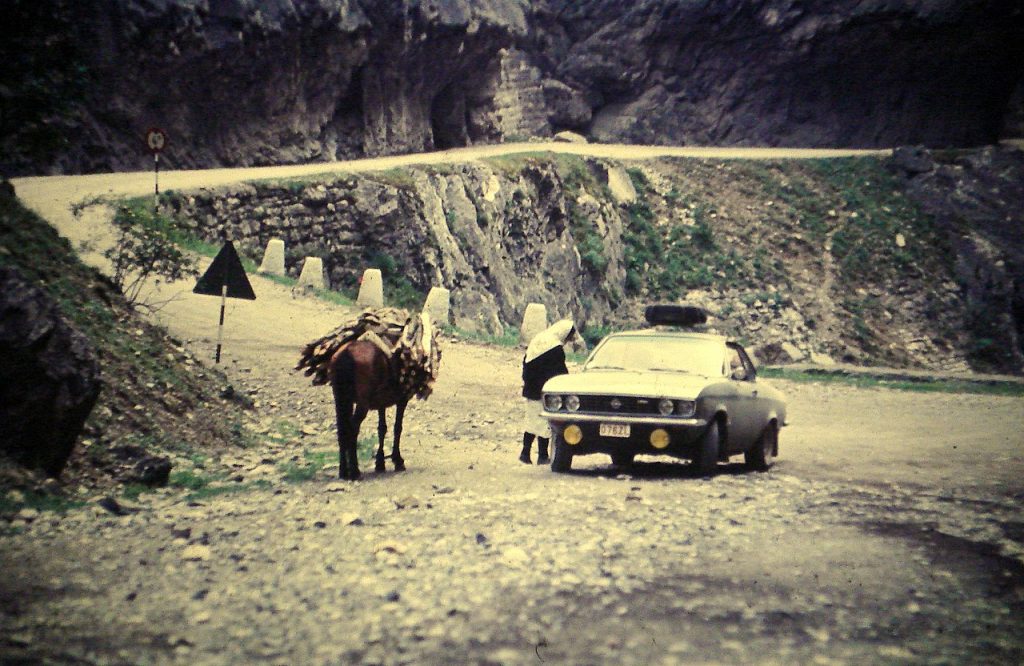

In early 1972, a public health threat penetrated Yugoslavia’s open borders, unwittingly carried in through the country’s periphery. A 35-year-old Albanian Muslim man named Ibrahim Hoti set out on hajj from his village of Danjane/Dejnë in western Kosovo, crossing eastward to Mecca. After completing the pilgrimage, he made his way back through Iraq, stopping at a market in Baghdad to pick up souvenirs. On his return on 15 February, he reported symptoms of fatigue and body aches, which he attributed to the long and arduous bus ride home.

Hoti recovered over a period of days, but another man a few miles away in Djakovica/Gjakova wasn’t as fortunate. Latif Mumdžić, a 30-year-old teacher, showed similar symptoms. Not suspecting smallpox, doctors administered penicillin, to which he had an adverse reaction. Mumdžić’s case was puzzling and, because his illness was particularly severe, he was reassigned to a hospital in Čačak in central Serbia, and subsequently to another in Belgrade. He died days after being admitted. No autopsy was done and Mumdžić was taken home to Novi Pazar, to be buried according to religious custom.

But the disease continued its insidious spread. Kosovo soon became the site of the largest outbreak of smallpox in Europe since World War Two. While it would remain impossible to trace precisely how the virus travelled from patient zero, there was abundant potential for transmission. On his return, Hoti had received visitors at his home – friends and relatives eager to congratulate him on his newly acquired status as hajji.

From the early 1970s, in line with the ambitions of the non-aligned movement, the Yugoslav state had adopted a more liberal stance toward religion. Yugoslav Muslims were now able to communicate and interact more freely with the wider Muslim ummah. Roughly 2,400 Yugoslav citizens embarked on the hajj each winter.

Although pilgrims were advised to travel by plane, for many the costs were prohibitive and they opted for chartered buses instead. The authorities had greater difficulty tracking such cases and monitoring their health upon return. Although the threat of smallpox was acknowledged – in Iraq especially – cholera appeared the more pressing danger. Hoti had been vaccinated for both. Mumdžić had not.

Rumours about Hoti’s motives circulated. According to some, he knew that he had the disease. But, heeding advice from religious leaders, who feared a backlash from state authorities, he had feigned ignorance. Others speculated that he had been smuggling goods from the Middle East. In the immediate wake of the outbreak, there were even suspicions of bioterrorism.

The state springs into action

Smallpox was eradicated in Yugoslavia in 1930, sooner than in the United States. After that, Yugoslav children were vaccinated against the virus at 18 months, at 7 years and at 14 years. Part of the male population was vaccinated during military service, which was compulsory for men aged between 18 and 27. Medical personnel were supposed to be vaccinated frequently, which wasn’t always the case. Other failures of the health care system also came to light, including resistance to vaccination measures, and claims that false vaccination cards and exemption certificates were in circulation.

Smallpox is a highly contagious virus that spreads through coughing, sneezing and direct skin contact. The incubation period ranges from 7 to 16 days. The symptoms are readily discernible and particularly unpleasant. Patients develop high fever, complain of fatigue and headaches, and break out in rashes and blisters, which eventually turn into scabs. Once the scabs have fallen off, the disease can no longer be transmitted.

Despite the government’s belatedness in detecting the incursion of smallpox, the response was swift and containment largely successful. As soon as the disease had been confirmed, the state declared martial law and undertook a massive re-vaccination campaign of some eighteen million citizens, including infants over three months, children and the elderly. Vaccination was mandatory for all. Pregnant women, diabetics and people with skin, heart and kidney conditions were urged to consult their doctor first. Vaccine donations came from the World Health Organization, the United States, West Germany, the Soviet Union, Switzerland and neighbouring countries including Bulgaria and Romania. The donations supplemented the country’s own paltry reserves.

On 16 March, about a month after Hoti’s return, the vaccination programme began in western Kosovo, followed a week later by efforts to vaccinate all the inhabitants of Belgrade. The vaccination programme prioritized areas where cases were found and extended outward from there. Quarantine facilities were set up in private homes, villages, hospitals and even motels. Movement to infected areas was restricted and checkpoints were set up where proof of vaccination was required. Public gatherings were prohibited. Since the virus was known to spread easily, even by touching infected items and surfaces, there were rigorous disinfection measures. By the end of March, nearly the entire population of Kosovo had been vaccinated.

In a news report on local TV, the leader of the League of Communists in Kosovo, Mahmut Bakalli, praised the efforts of doctors who had arrived from other Yugoslav republics to contain the spread of the virus. Documentary footage depicts a group of volunteer nurses who put their own lives at risk to assist on the front lines. Doctors from Karlovac and Zagreb in Croatia, and Ljubljana in Slovenia also went to Gjakova to assist the vaccination efforts. Eighty teams of personnel were dispersed throughout the affected areas of Kosovo.

By the time the epidemic was declared to have ended on 10 May, 175 people had been infected and thirty-five had died, mostly in and around Kosovo. But while the death toll could have been much higher, the epidemic dealt a heavy blow to the Kosovan economy. Closures on commerce and trade resulted in shortages. In April, the Belgrade daily Politika reported that the towns of Djakovica/Gjakova and Orahovac/Rahovec in the south-west were in need of flour, sugar and meat. In Prizren in the south, a boycott on industrial exports to Belgrade and elsewhere – including textiles, shoes and preserved food – was causing alarm in the population. In Hoti’s home village of Danjane/Denjë, eighteen families in quarantine were in desperate need of food and supplies, and there was no one to cultivate their land and tend to their vineyards.

Physician checking immunization reaction of a man vaccinated during the smallpox epidemic in Kosovo, Yugoslavia, March/April 1972. Author: Dr. William Foege. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Cracks in the healthcare system

Kosovo was the poorest and least developed region in Yugoslavia. Debates for greater investment in Kosovo’s infrastructure focused on public sanitation and public health, particularly in the more rural and inaccessible areas. In addition to chronically low access to clean water and a lack of adequate sewage systems came a heavy population density and a high rate of unemployment.

Deficiencies in the healthcare system also impacted the emergency response to the disease. The vaccine administered in Kosovo during the first eight days of the programme was of low quality. Practitioners who administered the vaccine were untrained and unprepared and a shortage of needles forced them to use alternatives like pens and styluses, which they put to a flame, dipped in the vaccine, and applied to patients’ forearms, a method that was extremely painful.

Approaching his eightieth birthday, Tito went conspicuously silent on the epidemic, which was uncharacteristic for a leader so adept at managing his public image. The handling of the crisis was left to health experts, ministers and civil servants. The virologist Ana Gligić was one of those at the helm of the state’s efforts to get rid of smallpox and became well-known after announcing the end of the epidemic. She was head of the laboratory of the Institute of Virology and Vaccines in Belgrade and charged with detecting positive patients and examining vaccines imported from abroad. In a recent interview, Gligić recalled the initial reluctance of the Yugoslav authorities to alert the public, not wanting to jeopardize the tourist season. During the COVID-19 pandemic she has re-emerged as a pundit and outspoken advocate of vaccination.

Although the epidemic was short-lived, it remained rooted in the public imagination. A number of artistic works sought to reckon with the collective fears and traumas provoked by this episode in the country’s history. In 1982, the leading Serbian director Goran Marković released the horror-cum-drama Variola Vera (the scientific term for smallpox). It became a box office hit and was seen by audiences in Hungary, Poland and elsewhere in Europe. Marković had long wanted to make a film inspired by Albert Camus’ The Plague and Yugoslavia’s experience with smallpox made the idea not only timely but financially feasible.

A relatively faithful retelling of events, Variola Vera is set inside a Belgrade hospital plastered with slogans urging prudence, good behaviour and strict hygiene: ‘clean hands for a clean bill of health’ and ‘let your actions be an example to others’. As advocacy for an ethics of public health grounded in the collective, they are injunctions that would be familiar to us today.

When Latif Mumdžić’s fictional analogue in the film, Halil Rexhepi, arrives at the hospital it is already a shambles. A bumbling repairman works on a broken furnace, while a workplace affair is in full swing just beyond closed doors. After patient zero is discovered, medical staff, patients and others are confined to the hospital and quarantined. An unsuspecting boy comes to the aid of the afflicted man covered in blisters, while everyone ignores his piercing cries of agony. The hospital, a place of refuge, morphs into a kind of house of horrors. As inspectors would later reveal, Yugoslavian hospitals were in fact a major site of transmission. A nurse, unable to endure the uncertainty, chaos and turmoil of illness and death, commits suicide. Outside, her son pleads to be reunited with her.

The film was a veiled critique of a ‘rotten society’. Talking in 2012, Marković claimed that the smallpox epidemic foretold the country’s eventual collapse. Indeed, a sense of foreboding pervaded the film. In an early scene, a man, presumably a Yugoslav Muslim, approaches a flute player at an oriental bazaar. A brief transaction later and the flute has changed hands. The tourist puts his lips to the mouthpiece, a small gesture auguring doom hundreds of miles away in the West. A poster for the film is similarly eerie, featuring a pair of hands on a flute surrounded by a pitch-black shadow.

In January 2021, Marković became something of a poster child for the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in Serbia. Interviewed by Reuters while standing in line to be given his jab, he quipped that he didn’t understand the scepticism towards the vaccine. He’d had the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine and had received vaccinations all his life, he reassured readers.

In 1983, the author Borislav Pekić followed suit with his novel Besnilo (‘Rabies’), a dystopian sci-fi novel that has also enjoyed a revival during the COVID-19 pandemic. It tells of an aggressive form of rabies introduced at London Heathrow Airport by a puppy smuggled onto a plane headed from Israel to New York City. By the end, all of the characters have died except the dog and a spectral figure in the form of a guardian angel. Pekić made an overt reference to The Plague in the final pages, reinforcing the pessimistic message throughout the novel that the danger of the disease and the ensuing chaos is always lurking.

Kosovo, 1972. Kosovo was the poorest and least developed region in Yugoslavia. Author: Jean Melis Source: Wikimedia

Experts and prejudices

The effective management of Yugoslavia’s smallpox epidemic has drawn much interest from contemporary observers of the current COVID-19 pandemic. Eighteen million Yugoslavs were re-vaccinated in a matter of weeks and the campaign garnered praise from the World Health Organization. The state’s response was swift and largely well-coordinated. However, it was not without its challenges. A team of experts was dispatched from the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), led by an American epidemiologist named J. Michael Lane, who had travelled to various places around the world affected by smallpox. The CDC had been established in the United States in the aftermath of World War Two to prevent the spread of malaria and was credited with eradicating smallpox on a global scale.

The CDC experts concluded that the state’s immediate recourse to mass vaccination had been misguided and premature, leading to oversights. They emphasized the need for better contact-tracing and surveillance. Although the official narrative was that Ibrahim Hoti had imported smallpox, the CDC team had difficulty accepting that someone with such a mild case of smallpox could have spread the virus so efficiently. These findings were instrumental in revising contingency plans in the event of a similar outbreak in the United States.

The CDC report also discussed the cultural factors of transmission. Albanian family structures, the architecture of houses in the affected region, and particularly the frequency of extended families living under one roof were understood to contribute to the high rate of infection.

At the time, Kosovo had a population of 1.1 million. The majority of inhabitants of the province were ethnically Albanian and predominately Muslim. Within Yugoslavia as a whole, however, Kosovo Albanians constituted a minority. The phenomenon of minority group as embodiment of public fear of the ‘Other’ – also evident during the coronavirus pandemic in the form of anti-Asian racism – merged with elements of public hysteria.

Cartoons published in Rilindja, Kosovo’s leading Albanian-language newspaper at the time, both pointed out and succumbed to the social prejudices that ran rampant as a result of the disease as well. In one cartoon, a hajji introduces himself to a customs officer with a sign bearing his name, implying a language barrier and apparent lack of cultural intelligibility between him and the state. It was indeed the case that a scarcity of Albanian-speaking epidemiologists hindered the authorities’ efforts to trace contact. But the cartoon was making another, more malevolent point. Written on the sign was ‘Hajji Alija’ with the first letter of the name struck through, a play on words for the Albanian term for smallpox, ‘lija’.

In another cartoon, a man is reading a newspaper. A passer-by stops to read the headline: ‘Suspicions that hajjis brought smallpox to the country’. When the man reading the newspaper folds it up and reveals himself to be wearing the traditional Muslim skullcap, the passer-by runs away. Such subtle expressions of narrow prejudice reveal the darker side of Yugoslavia’s smallpox outbreak, and contrast sharply with official government rhetoric and reports.

Lessons for today

From today’s perspective, however, another problem identified by the CDC stands out. In 1972, vaccination efforts were hampered by ‘an irrational set of contraindications to vaccination’, something that ‘should not happen in the United States’. The freedom to choose not to be vaccinated did not exist in Yugoslavia in 1972, however. More importantly still, the public largely accepted the state’s emergency measures.

Today, the tide has shifted. Many citizens of the former Yugoslavia remain sceptical toward the COVID-19 vaccination. Slovenia has the highest share of people fully vaccinated, but at 59% is still considerably below the EU average of 73%. Croatia comes next with a share of 55%. North Macedonia has the lowest share at 40%, followed by Montenegro (45%), Kosovo (46%) and Serbia (48%). Other former communist countries in south eastern Europe have even lower rates: Romania has a share of 28% and Bulgaria only 18%. In central eastern Europe, rates are around ten percentage points higher than the Western Balkans (with the exception of Slovakia at 51%). In the Baltics, on the other hand, vaccination rates are nearer the EU average. Clearly, the communist experience alone does not account for resistance to vaccination programs.

As disinformation continues to spread through various channels, the global anti-vaccine movement has dogged efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19. People are emboldened by celebrities who flout medical experts’ advice: Serbian tennis superstar Novak Djoković being the most prominent example. Djoković has been touted as a national hero, his actions garnering support from far-right nationalists who saw his detainment by the Australia immigration authorities as another example of Serbs being unfairly targeted by the West. With or without nationalist overtones, however, distrust in government and western medicine has contributed to vaccine hesitancy.

Even as states begin lifting restrictions, the question of how to manage health crises in the contemporary world remains. What kind of society will the COVID-19 pandemic leave behind? In the aftermath of the Yugoslavian epidemic, one Kosovan journalist urged people to band together to deal with its psychological and economic consequences. Kosovans no longer needed to fear the people of Gjakova, Rahovec or Prizren; the other republics and provinces no longer needed to fear Kosovans; and the outside world no longer needed to fear Yugoslavia. The lesson might just as well be applied to the present day. When fear and isolation dissipate, it becomes imperative that we re-build a sense of community and solidarity.