Writing is a known tool for healing trauma. And poetry lends itself to rapid responses under pressure. Forced into migrating to flee war, many Ukrainian women turn to the short form as a call of solidarity, a weapon and solace.

Plenty of women are working as correspondents and reporters, but relatively few as opinion writers and editors. And while the gender gap in print is insidious, in broadcast media it’s glaringly obvious, writes Dawn Foster. Meanwhile, the gentrification of the media continues apace.

Can girls even find Syria on a map? Jill Filipovic’s (tongue in cheek) rejoinder on the Guardian website last month1 aimed to poke fun at the bias in commissioning opinion pieces on foreign policy issues, noting the heavy weighting towards male bylines on the pages of the New York Times and the Washington Post. Filipovic’s piece swiftly garnered a huge response online, and an article from BuzzFeed‘s Sheera Frenkel claimed that most correspondents covering the Syrian conflict were women.2 Filipovic’s central argument wasn’t disputed by Frenkel – the vast majority of opinion writers embraced across the global media continue to be male.

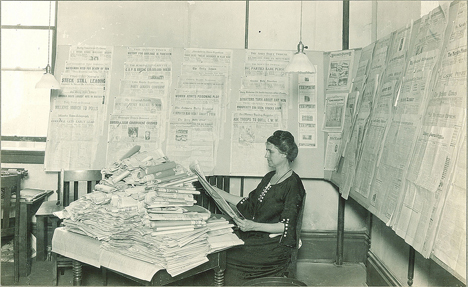

Close Hall, University of Iowa, 1920s. Photo: University of Iowa Libraries. Source: Flickr

This matters, because it frames the national debate, and in the case of Syria, influences political decision on military intervention, purporting to be a bell-weather for public opinion at large. If there are plenty of women working as correspondents and reporters, but relatively few female opinion writers and editors, then this indicates a problem in the industry. Women may be blogging more, make up more than 50 per cent of Twitter users3, and piling into varieties of journalism, but the biggest newspapers in the United States, Britain and Europe still reserve pages of the most serious political and foreign policy analysis for older men, and unsurprisingly, they’re usually white.

A study by Women in Journalism earlier this year found that across national newspapers, 78 per cent of bylined front page stories were written by men, and of those quoted as experts or sources in lead stories, 84 per cent were men.4 The Women’s Media Centre in the United States, on conducting similar research reported that during the 2012 presidential election, 75 per cent of front page bylined articles at top newspapers were written by men and that women made up a mere 14 per cent of Sunday TV talk show interviewees, and 29 per cent of “roundtable” guests.5 Women in Journalism were quick to highlight one of the most worrying aspects of this imbalance: most stories involving women in the four week period surveyed, portrayed them as either victims or celebrities.

While the gender gap in print is insidious, in broadcast media it’s glaringly obvious where radio stations and TV programmes are failing. BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, long criticised for a dearth of female guests, provoked outrage when, during a segment on breast cancer, they admitted on air they’d failed to find any women to discuss the issue. Instead, they asked a male guest to “imagine” he was female for the purpose of the discussion. It was this that prompted Caroline Criado-Perez to launch “The Women’s Room”6 – an online database of female journalists listed by expertise.

Helen Zaltzman, a broadcaster and podcaster who produces the pressure group Sound Women’s podcast points out “Only around one in five presenters on British radio is female, yet slightly more than half the audience is. And who knows what proportion of those on-air voices are allowed to do more than laugh sycophantically at their male co-presenter’s jokes? It would be great if, whenever jobs opened up, execs resolved to give more of them to people who aren’t white men”. Many female journalists discuss the struggle to get their voices heard on news coverage of any issue that isn’t seen to be “soft” or a gender issue. On foreign policy, there’s a running joke amongst female journalists that every story on the Middle East has a woefully ill-informed male commentator decisively informing presenters “it’s too early to say” in answer to any question that can’t be easily bluffed – there’s a tendency for men to put themselves forward as knowledgeable on all manner of subjects, and producers to accept this authority, whereas women tend to focus on areas of specific expertise.

Ian Katz, the new editor of BBC2’s Newsnight publicly acknowledged the problem the programme had with recruiting women as panellists, but took to Twitter to say the issue was harder to correct than he’d anticipated: “After whingeing for years about shortage of women guests on shows like Newsnight am feeling a bit more sympathetic”.7 Several months before Katz’s arrival, Newsnight ran a panel on the eurozone crisis that comprised of four women discussing economics. Zoe Williams, a Guardian columnist, noted it was such a rare sight that someone had taken a photo of it for posterity.8 The Today programme and Newsnight act as two of the most serious flagship news and analysis programmes on television: if women are systematically excluded from them, or only brought on to discuss narrow topics, the message is implicit that women’s voices and opinions aren’t valued, that female journalists aren’t considered “serious” or “heavyweight” enough to be a ratings draw.

When women do get heard, it’s often on a limited range of subjects. Women, far more than men, are expected to put themselves at the centre of stories, or plunder their own lives for material. Male experience is treated empirically, and straight reporting seen as the norm, whereas women are expected to have, and share, first person experience, often at the expense of their own privacy. Given its reputation for unabashed sexism, it’s initially surprising to see that the Daily Mail is the British national with the most equal (in the loosest sense of the word) distribution of bylines.9 But this is the paper that institutes a “no trousers” policy when photographing female writers at the behest of its editor, Paul Dacre, and deliberately sets up journalists like Samantha Brick and Liz Jones as hate figures within its pages, running them alongside the infamous “Sidebar of Shame”.

Dan Catt looked at the gender of bylines on the Guardian for one month and found “For the month of September there were 7862 articles written with 8927 bylines, some articles have more than one byline. There were 2617 female (29.3 per cent), 6030 male (67.6 per cent) and 280 “other” (3.1 per cent) bylines, just under a third of all bylines are by women. As it turns out there are only five sections where female bylines outnumber male bylines: Fashion, Education, Life and style, Money and Travel. That’s five sections out of 26 in total. With women’s writing still skewed towards consumer journalism, or “soft” subjects there comes another problem: women’s writing often gets labelled as “life and style” regardless of the content.

Reni Eddo-Lodge, a journalist and campaigner says “I keep finding my work leaning toward an introspective and personal manner – a style of writing that is highly gendered. Whilst I recognise the value in this style of writing, it’s too easy to dismiss as ‘female’. I have radical political theory behind my writing – it’s why I write. My articles aren’t just diary entries but I worry that my perspective is received as not ‘objective’ because unlike straight, cis, middle class white men, I don’t pretend that it is”. This is reflected in some of the abuse women writers suffer online. Being encouraged to write “from experience” precludes opening yourself to personal attack, and a more barbed criticism than readers merely disagreeing with your opinions. It’s common to see online commentators construct an image of women writers’ personal lives, and attempt to use this to discredit their opinions. Predictably, this often reverts to sexist tropes and misogynistic abuse.

The problems facing women’s representation in media increase with age too, no more so than in broadcasting. After Miriam O’Reilly won a legal battle against the BBC, proving she was unfairly dismissed from her role as a presenter on Countryfile, the broadcaster commissioned a survey with NatCen on the portrayal of age across its channels. The study found that, unsurprisingly, younger people were most often shown on its programmes, but that there was a particular dearth of middle-aged and older women across all genres of shows.

The hackneyed, but immortal, presenting trope of a greying, middle-aged man, flanked by a heavily groomed woman half his age is a case in point – Andrew Neil’s broadcasting career seems in no danger of waning as the wrinkles increase, but for women across British TV channels, the march towards their forties signals an employment precipice. In their report on ageism and media, Women in Journalism found 60 per cent of women over 45 felt they’d experienced ageism.10 Women are finding doors closed to them at the exact point men are still developing their careers and entering the most senior levels of journalism.

Rachel Shabi, an analyst and journalist focussing on the Middle East spoke of “the far higher burden of proof required if you’re female, a minority or not from an upper middle class background, because of the staggering force of all the invisible or denied hierarchies of power and access that operate within British media. You keep jumping the bars, but they keep rising even higher and you’re always at the same starting point regardless of talent, experience or track record. Eventually, many women, many minorities, will just stop trying – because that kind of effort, in the face of ever-shifting targets, simply isn’t sustainable.”11

Shabi’s description of constant small-scale setbacks contributing to wider exclusion of women echoes a recent New York Times article, in which Eileen Pollack spoke of how she feels women are still underrepresented in science due to the “slow drumbeat of being under-appreciated, feeling uncomfortable and encountering roadblocks along the path to success”.12 Many of the excuses for the lack of diversity in journalism, the further up the ranks you go, tend to be directed at individuals or rely on tropes and stereotypes. Women just aren’t “pushy” enough, or aren’t “self-promoting”, wilfully ignoring the structures that cause the imbalances, and forcing the blame back onto the individual, failing to acknowledge that if it were a problem of individual, rather than systemic, failings, there appear to be rather a lot of individuals coincidentally experiencing that same problem in the same industry.

Particularly worrying is the march towards freelance working, and especially on the web, free labour in journalism as staff jobs dwindle in mainstream media. With freelance work often depending on contacts and being able to get an editor’s ear, if staff jobs dwindle as paper revenues continue to fall, it’s unlikely the people to lose out will be the more affluent and connected men. Redundancies have become the norm in global media as newspapers and magazines recalibrate their content to reflect the switch to online media’s dominance. Moving towards an industry model that relies on journalists to be “pushy” and self-confident reinforces the success of those who’ve never struggled in the first place, and means groups who’ve had to fight to be heard in the mainstream media lose out, especially if they don’t have a financial safety net, and can’t work for free. Consider it the gentrification of the media.

An examined look at the factors involved in perpetuating imbalances across the media involves the antithesis of the powerful: recognizing that meritocracy is in essence a facade. It’s an uncomfortable fact to consider and admit that your achievements may be down to luck and subconscious decisions employers have made about you, rather than simply “hard work”. The current cabinet of overwhelmingly white, male, privately educated politicians living on inherited wealth may well believe they’ve entered the highest echelons of power as a result of their merit, but a quick look at their employment history reveals that, consciously or not, these “horny-handed sons of toil” found doors open where others met only walls. Psychologically, we always believe we’ve made the best decisions in employing and commissioning people. It’s only by actually acknowledging power dynamics, and actively working to dispel preconceptions about what a commentator looks and sounds like we can actually diversify the voices we hear in the media.

Jill Filipovic, "Can girls even find Syria on a map?", Guardian, 13 September 2013, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/sep/13/syria-almost-no-female-voices-in-debate

Sheera Frenkel, "Women are covering the hell out of the Syria war: So why haven't you noticed?", BuzzFeed, 15 September 2013, www.buzzfeed.com/sheerafrenkel/women-are-covering-the-hell-out-of-the-syria-war-so-why-have

Lauren Dugan, "The typical Twitter user is a 37 year old female [STATS]", 4 September 2012, www.mediabistro.com/alltwitter/twitter-age-gender-2012_b27885

Amelia Hill, "Sexist stereotypes dominate front pages of British newspapers, research finds"

Guardian, 14 October 2012, www.theguardian.com/media/2012/oct/14/sexist-stereotypes-front-pages-newspapers

Alexandra Campbell, "The lady vanishes -- at 45", womeninjournalism.co.uk/the-lady-vanishes-at-45/

Rachel Shabi, "Why is the media debate about Syria dominated by men?", Guardian/The Women's Blog

Monday 30 September, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/the-womens-blog-with-jane-martinson/2013/sep/30/media-debate-syria-white-men

Eileen Pollack, "Why are there Still so few women in science?", The New York Times, 3 October 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/magazine/why-are-there-still-so-few-women-in-science.html?_r=0

Published 18 October 2013

Original in English

First published by openDemocracy (50:50 section), 14 October 2013

Contributed by openDemocracy © Dawn Foster / openDemocracy / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Writing is a known tool for healing trauma. And poetry lends itself to rapid responses under pressure. Forced into migrating to flee war, many Ukrainian women turn to the short form as a call of solidarity, a weapon and solace.

The responsibility for family and home, often while holding down a job, is still largely considered women’s work. When crises strike and recession looms, those in precarious jobs tend to suffer the most. In Italy, the burden of economic fallout has fallen on female shoulders. But women’s acumen is behind a turnaround.