Three weeks ago London marked the sixth anniversary of the 7/7 bombings. Now Oslo will have its own heart-wrenching day of remembrance every year. Even for those who lived through 7/7 – not to mention countless other bombings, from IRA to neo-Nazi, that London has witnessed in the past few decades – there was still something viscerally shocking about Anders Behring Breivik’s murderous rampage through Oslo and Utøya. The mindlessness of the massacre combined with its cold-eyed homicidal brutality.

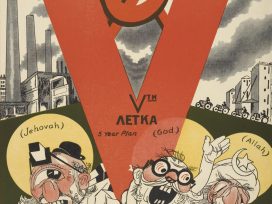

It was inevitable, perhaps, that Breivik’s attack would first be portrayed as an Islamist plot. For some, any form of terrorism is marked “Muslim” and they wish to look no further. The irony, however, is not just that Breivik’s hatred of Islam should lead to a horror that many took to be Islamic, but also that nothing so resembles Breivik’s mindset as that of an Islamist jihadist.

It was inevitable, perhaps, that Breivik’s attack would first be portrayed as an Islamist plot. For some, any form of terrorism is marked “Muslim” and they wish to look no further. The irony, however, is not just that Breivik’s hatred of Islam should lead to a horror that many took to be Islamic, but also that nothing so resembles Breivik’s mindset as that of an Islamist jihadist.

Jihadists view themselves as political soldiers, bringing terror to the West in response to western interference in Muslim lands. Breivik believes he is waging war against the Muslim takeover of a Christian Europe. Both use the language of the “clash of civilizations” to justify their atrocities. In some sense, their perverted ideology drove their actions. But in neither case are these political acts in any traditional sense. Rather, what unites Breivik and the jihadists is the arbitrary, nihilistic character of their violence that, for all their rhetoric, is disengaged from any political cause.

When, last year, Taimour Abdulwahab al-Abdaly attempted to bring carnage to the streets of Stockholm by trying to blow himself up amongst a crowd of Christmas shoppers, I wrote in Sweden’s Expressen, that “The first lesson is the need flatly to reject the fiction that the bombing was a response, however perverted, to some sense of political grievance.” The bombing “was no more a response to Muslim grievances (real or perceived) than the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing in America was a response to the perceived evils of the US government.” Al-Abdaly, I observed, “seems to have been driven not so much by political fury as by a hatred for the world around him and a deep indifference to the consequences of his actions. However far you stretch the concept of ‘political’, it is nevertheless still impossible to imagine how setting out to murder dozens of Christmas shoppers could be any kind of political response.”

This has been true of every Islamist bombing. It was true of the Oklahoma City outrage. And it is true of the Utøya massacre.

Both jihadists and Breivik seem to be driven not so much by political ideology as by a desperate and perverted search for identity, a search shaped by a sense of cultural paranoia, a cloying self-pity and a claustrophobic victimhood. Islamists want to resurrect an “authentic” Islam that never existed in the first place and to enforce that identity upon all Muslims. Breivik similarly wants to establish an authentically Christian Europe, again that has never existed, swept clean of Muslim pollution. His use of the red cross symbol of the Knight Templars suggests a Christianity learnt from the pages of Dan Brown.

All this makes ironic Breivik’s assault on multiculturalism. Multiculturalism has in recent years come to have two meanings that are all too rarely distinguished. It refers to a society made diverse by mass immigration. It also refers to the political policies necessary to manage such diversity. The problem with such policies is that by forcing people into ethnic and cultural boxes, they undermine much of what is valuable about diversity and weaken the idea of a common citizenship.

I have long been a defender of diversity but a critic of multiculturalism. Breivik, on the other hand, opposes diversity precisely because he wants to put people into cultural boxes. The irony is that for all his hatred of multiculturalism, Breivik’s belief in the “clash of civilizations” draws upon notions of cultural difference and identity not that estranged from those that animate many multicultural policies. In this, too, he reveals his similarity to Islamist jihadists.

Perhaps the most important similarity between Breivik and jihadists is that both despise the idea of an open, liberal society, shaped by debate, dialogue and the clash of diverse values and beliefs and amenable to change. That is why it is important not to listen to the growing chorus of voices that suggest that the key lesson to be learnt from Breivik’s terror is that Norway has become too open, too liberal and too tolerant a nation, too slack in its security, too unprepared for horrors such as this.

Over the past ten years, the response to Islamic jihadism in Britain, America and elsewhere has been shaped by a sense of fear and panic that has made it far easier for the authorities to increase surveillance, extend police powers, and erode free speech. The war on terror has led to such abominations as Guantanamo Bay, “extraordinary rendition” and torture. In trampling down on fundamental liberties in this fashion Western leaders have in effect done the terrorists’ work for them.

The same must not be allowed to happen in response to Breivik. Just as the Right has stoked up fears about the “Muslim takeover” of the West and about the creation of “Eurabia”, so many on the left are now promoting alarm about a neo-fascist network intent on sowing terror. There is, in fact, no evidence that Breivik was part of any conspiracy involving neo-fascist groups. Nor is there even much evidence that attacks such as Breivik’s are linked to the strength of far-right ideology. As the academic Robert Ford, a leading researcher into far-right movements, has pointed out, there is “no research showing massacres occur more frequently in countries with prominent extreme right movements than in countries without such movements”. We need to challenge neo-fascism and anti-Muslim bigotry, just as we need to challenge Islamism, But in both cases we also need to keep a sense of perspective about the nature of the threat.

Norway’s relative openness and liberalism are among its best attributes. If the nation were to become closed, illiberal and paranoid it would be no safer. But Breivik would have won.

It was inevitable, perhaps, that Breivik’s attack would first be portrayed as an Islamist plot. For some, any form of terrorism is marked “Muslim” and they wish to look no further. The irony, however, is not just that Breivik’s hatred of Islam should lead to a horror that many took to be Islamic, but also that nothing so resembles Breivik’s mindset as that of an Islamist jihadist.

It was inevitable, perhaps, that Breivik’s attack would first be portrayed as an Islamist plot. For some, any form of terrorism is marked “Muslim” and they wish to look no further. The irony, however, is not just that Breivik’s hatred of Islam should lead to a horror that many took to be Islamic, but also that nothing so resembles Breivik’s mindset as that of an Islamist jihadist.