In an Amman rehearsal room are Syrian TV matinee idol Newar Bulbal, Syrian amateur actor Azmi Al Hassany, 26, and Raneen Ibraheem Aga, 23, a Syrian refugee. They are all taking part in a ground-breaking radio drama We Are All Refugees, inspired by the long-running UK radio soap opera The Archers. The refugee drama is broadcast globally on Radio Souriali, an independent Syrian station transmitted from Jordan and Syria. It is also aired in the US and via the United Nations website.

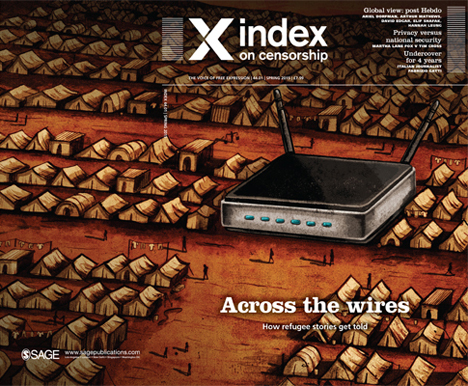

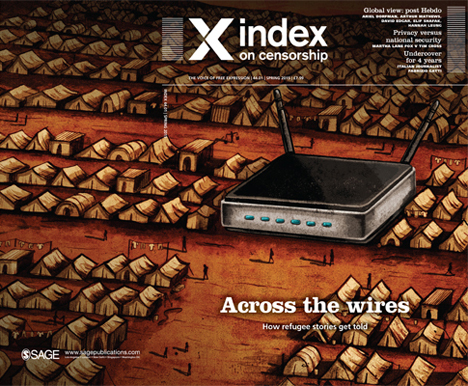

Almir Koldzic and Áine O’Brien’s article is a contribution to the spring issue of, entitled. The article is part of a dossier on everyday life in and around the world’s refugee camps. Cover art: Ben Jennings.

Georgina Paget, who co-produces the project with Charlotte Eagar, discusses what the project hopes to achieve: “In simple terms, the radio project aims to reach as many Syrian refugees and members of their Jordanian community as possible, with dramatized presentation of topical and relevant issues about their daily lives. It aims to help all elements of the community to have a greater and deeper understanding of the situations of others living side by side with them and highlight the benefits of understanding co-operation.”

The team’s ambition is to gain a long-term commission for the series on either radio or television. To bolster the series’ credentials they have assembled a group of established screen actors to join with refugees, co- creators and producers. The series is partly funded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the title We Are All Refugees has echoes of philosopher Hannah Arendt’s 1943 essay, “We Refugees”. Some 70 years later, the radio soap explores themes that now have every day and ordinary resonance, such as forced or arranged marriages for young Syrian refugee girls, domestic violence, unemployment and water shortages. It also looks at the predicament of young Syrians not allowed to work legally in Jordan and the tensions between two communities living side by side.

More than 50 million people are displaced globally, according to the UNHCR. Yet many of the images in the media are emptied of the nuanced details and the day-to-day challenges of refugee camp life. That’s why there are increasing attempts by refugee agencies and other organizations to tell refugees’ stories and make their experiences come alive. As the British writer, AA Gill, who won an award for his articles from refugee camps, puts it: “The hot news story is the conflict itself; this intransigent, complex headache of unwanted, awkward, lumpen people doesn’t have the dynamic interest of global politics or the screen-grab of smoke and bodies and Kalashnikovs.”

In the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, for instance, a United Nations’ project is working with US-based photojournalist Brendan Bannon, to equip young refugees with cameras, so they can take photos and write about their personal histories and memories. Their work has been published online and in newspapers. “We promised to give the kids a voice through photography”, said Bannon. “I have heard from so many people who have seen the kids work in The New York Times and online. I am sure that the pictures are challenging preconceptions about refugee life. I hope that the work can be more widely seen in places where refugees are living today.”

Alaa, 14, fled with her family from Dara’a in Syria. She now takes photos of family, friends, neighbours in Zaatari. As the family and community chronicler, she re-imagines and documents what has been lost, discovering a voice through photography: “Although I’m shy”, says Alaa. “I had no problem showing my work and talking about it in class. We all learned to look after each other.” If she could photograph anything, it would be her house in Syria and the beautiful countryside surrounding it. “I can still remember the trees and the smell of the soil.”

On UNHCR’s Tracks website refugees tell their own stories from camps or en route to sanctuary. There are experiments in immersive storytelling and the authors use photography, video and sound. Some stories are written by journalists commissioned by the UNHCR, such as those within the Family Ties section, charting the journeys of Syrian Kurds who find refuge with their extended families in Turkey. Istanbul-based multimedia journalist Lauren Bohn tells the story of Ibrahim:

“When 41-year-old Ibrahim, one of the most cherished bread makers in the Turkish city of Suruc, heard the news that Isis was surrounding his uncle Veysi’s village near Kobane, also known as Ayn Al Arab, he rushed to grab his mobile phone. ‘I told them to get out of there right away… to come here’, he says, in the small grey courtyard of his apartment, tucked away behind his bakery just a few miles from the Syrian border. ‘It’s just as much their home as it is ours.’ So Veysi, his wife and children packed up as much as they could – some clothes, a few books and family jewellery – and fled to the border. Ibrahim, still wearing his baker’s smock, was there to greet them. ‘The Kurdish life in Syria, and everywhere, has always been hard’, says Veysi. ‘But this is something we never imagined.'”

Stories on the Tracks website come from all over the world: from the Zaatari camp in Jordan, from northern Iraq and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Some are told from European makeshift camps like the ones in Pozzallo, Sicily or Calais, France. And soon Tracks will be inviting user-generated content so the website can help create a conversation with the wider world and refugees via social media. Another media project, Dadaab Stories, which has a lively website, is dedicated to telling stories from the enormous Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, near the border with Somalia.

Describing itself as a “collaborative community project”, Dadaab Stories is an initiative run by FilmAid, which has been working in the camp screening, teaching and making films since 2006. It is funded by the Tribeca Film Institute New Media Fund and the Ford Foundation. Dadaab is one of the largest refugee camps in the world and “home” to approximately half a million people. The sheer scale of Dadaab is reflected in the different generations living in the camp. As the FilmAid website puts it: “By definition, a refugee camp is temporary, but life does not stop here. Love, marriage, children, work, art – life goes on. After two decades, there are more than 8000 Dadaab grandchildren, children of children who were born in the camp.”

Unlike Tracks, which casts its storytelling net globally and across refugee camps in different countries, settlements and diaspora locations, Dadaab Stories is firmly anchored in everyday camp life. While it includes perspectives from diaspora communities, the main focus is on communications within the camp through personal videos, journalism, photography, poetry and music. Powered by the social media platform, Tumblr, this is community media at its liveliest.

One of the camp’s media services led by refugees and forming part of Dadaab Stories is The Refugee News, a community-run newspaper and the only local print media outlet for the population of 500,000. It is edited by a dedicated group of volunteer journalists that come from the refugee communities within the camp, with training and facilities provided by FilmAid. The Refugee News also includes a radio station called Gargaar (Somali for assistance), supported by the international non-profit organization Internews, whose mission is to strengthen local media worldwide, enabling local people to circulate and hear much-needed news and information. The refugee journalists working on Radio Gargaar are all trained by Internews, with some working as professional journalists before coming to live in Dadaab.

The Syrian Trojan Women project for refugee women in Amman, Jordan, also co-produced by Charlotte Eagar and Georgina Paget, is using the classic Euripides anti-war tragedy to interweave drama therapy workshops, participatory storytelling and public performance, in addition to promoting understanding between refugees and host communities in Jordan. The drama workshops help refugee women who are suffering from mental anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. When possible, the women are paid to participate.

This relatively modest project began in 2013 with small-scale workshops in Amman and has since spawned several spin-offs including a documentary film, entitled Queens of Syria, chronicling the project’s participatory methodology, and a Trojan Women tour to the US and Switzerland. Queens of Syria was shot and directed by filmmaker Yasmin Fedaa. Fedaa engaged closely with the cast of refugee women by spending time with them in their homes and integrating the women’s personal stories into the film. The aim is to screen Queens of Syria in refugee camps, at international film festivals and on television.

It is clear that we are witnessing the many ways in which photography and film, the visual arts, theatre, mixed-media storytelling and online journalism are transforming the idea that refugees are voiceless victims.