Snapshots of the war in Donbas

How the conflict in Ukraine affects the lives of those on the front

Paweł Pieniążek has covered the war in eastern Ukraine from all sides since it broke out in spring 2014. He was one of the first journalists on the scene of the MH17 airliner disaster. Here, translated into English for the first time from his book ‘The War that Changed Us’, is some of his reportage from the front line.

Author’s note

The first time I went to Donbas was in the middle of April 2014. I was sure that I would be covering another wave of protests, and that after the Euromaidan protets, an ‘Anti-Maidan’ would emerge. In March, pro-Russian protests were already developing and nobody was thinking about war – especially me. I was not prepared to cover a conflict and I did not expect to find it interesting. However, just before my arrival separatists seized a few Ukrainian armoured vehicles. Almost accidentally, I appeared in the conflict zone at this time.

I hated war and still do, but I got used to it. After April 2014, I spent many months in Donbas and reported from both sides of the conflicts. I witnessed the catastrophe of the downed MH17 airliner, and the intense battle for the suburbs of Donetsk.

I found the processes and mechanisms of the war really interesting, because they show people as if through a lens. George Orwell wrote that war ‘speeds up all processes, wipes out minor distinctions, brings realities to the surface.’ During my numerous trips to Donbas, I was looking for these universal problems which people are made to face during every conflict.

‘They get back to work’

Life in the northern reaches of Donetsk lasts only a few hours: from the end of one bombardment to the beginning of the next. That is when you can emerge from the basement into the light of day.

The first time I visited Volodymyr, who lives in the Donetsk neighbourhood of Zhovtneve, was in October 2014. Officially, Zhovtneve is still part of the city, but it looks like a neighbouring village. In Russian this is called a poselok. The buildings are predominantly low-rise, but there are also apartment blocks. In the autumn, the missiles fell one after another. There was not a single day with so much as a few hours of peace. Many people died, many more left. Many buildings were damaged or destroyed. The Ukrainian army was in theory firing at military targets, which were indeed present in Zhovtneve, but they often missed, with terrible consequences. This was usually the result of faulty artillery or inaccurate coordinates, but sometimes the soldiers simply did not care where their missiles fell. When I visit Zhovtneve again a year later, not much has changed. The fighting has calmed down a little, but the poselok is even more depressing. This is one of a few places where the usual rule of ‘We start at 7pm’ has not applied for most of the war. Here the daily rhythm begins at 4pm.

I show Volodymyr the traces of shrapnel on the façade of his house. They were not there the first time we met. ‘It’s been a long time since we noticed such things,’ he says.

When he invited me in for Gypsy tea with apples and honey, I got a sense of what he meant. A few months earlier, a Grad rocket had struck a tree in his yard, bringing down one wall of the house and part of the roof. A wire from the guidance system of an anti-tank missile still hangs above the yard. ‘It hit the neighbour’s,’ he says, pointing at the building next door, a hole in the wall of its second floor.

Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

Fortunately, Volodymyr has a basement with an entrance next to the house. He hides there with his wife and small child, although the shelter does not look especially solid.

‘If a missile hits the door, we won’t be able to get out,’ he admits.

For now, the entrance is intact. Volodymyr does not have any plans to leave. He is afraid that everything would be stolen by the thieves who roam abandoned buildings.

Like everyone here, Volodymyr is waiting for life to return to normal. He remains optimistic. ‘When all of this is over, we’ll go fishing together and have a drink,’ he says, smiling.

He says this every time we meet, but there are still few indications that his dream will ever be realized.

For now, there are no reasons for joy. Right next to Volodymyr’s house is the bazaar, or what’s left of it. A few stands still operate during the day.

‘When a missile comes, everyone falls to the ground, then they get up and continue trading. People have got used to this kind of life,’ says Ruslan, the imam at the nearby mosque.

At the bazaar almost everything is burned out, scattered with debris. The ground is littered with the remains of market stands and their contents.

Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

A few hours before my arrival, a missile hit the roof of a building on the other side of the street, while a second struck the ground a few dozen metres away. As always, the windows shattered and holes appeared in the walls, some the size of a fingernail, others the size of a finger, some even the size of a fist. Each missile makes a terrible mess. Glass, plaster, tiles – anything that can fall off a building crashes to the ground. A group of women is trying to return the yard to order. They run around with brooms and buckets. ‘Tell us, when will all of this end?’ they ask, as if in chorus.

I do not have an answer, so they get back to work.

Moments earlier, I had a chance to speak with one of the women. Her name is Olena. She came up to me and launched into a monologue. I noticed that she was drunk, and at the same time shaken, completely crushed.

‘I can’t take this any more. I sent everyone away, and now I’m left on my own. One cannot abandon one’s home, isn’t that true? You would never do such a thing,’ she states, although I have no idea what I would do, and I am glad that I am not faced with such a decision. She continues with a raised, shaky voice: ‘I stayed because this is my home, and I do not want to be homeless. I want to live here.’ She begins to cry and falls to her knees. ‘What must I do for all of this to end?! What?!’ she sobs. She is calmed down by Iryna, who remains completely composed. ‘Come, we have to get back to work,’ she tells the drunken woman. Olena obeys.

Although there is not much to do here, people are often in a hurry. Three men are affixing fibreboard to cover up a broken window. One of them says, ‘I would gladly talk to you, but we have to fix this up quickly. The shelling will start soon.’

Every day they clean and repair, even though the next day everything will be destroyed again. This is a Sisyphean effort, one that they are engaging in consciously. Why do they do this? They are unable to provide a convincing answer. I think they want to maintain a sense of control over a reality that has slipped out of their hands. And demonstrate that they do not agree with the laws brutally imposed by war. They are trying to carve out a space in which, even for a moment, they can have an impact on what is happening – even if that impact is limited and illusory. Moreover, this is an attempt to return to the routine that used to govern their lives, that basic human necessity – those daily activities that we pay no attention to, and whose sudden absence makes us feel as if something important has been taken from us. Through these small gestures, the inhabitants of Donetsk are fighting for the normality they have unexpectedly been deprived of. This is how they maintain their sanity in this theatre of senseless violence and contempt for life.

***

Before the bazaar burned down completely, Iryna sold cleaning supplies. Now she has nowhere to sell, and there are fewer and fewer people in Zhovtneve who can afford such expenditure. Finances are tight. Residents live mainly off of the humanitarian aid handed out by various organizations, which they collect in the morning in order to get home before 4pm. This is zero hour, after which everything dies down and everyone descends into their basements.

Iryna lives in a solid multi-storey building with a fairly spacious podval, or basement. This is a more promising shelter than a single-family house like Volodymyr’s. There are four other people living with her underground: three from her entryway and a seriously ill elderly woman from the neighbouring building, whom Iryna looks after. ‘You want to do something good, help others somehow.’

Iryna in her basement. Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

They have mattresses and some old furniture. On the desk next to her bed Iryna has placed those objects she deems indispensable: an image of the Virgin Mary, water, a glass, cigarettes, matches, a spoon. There is also a light bulb, in case the one illuminating the room burns out. Light always gives some hope. For now the podval is empty; it will not fill up until 4pm.

Iryna tries to smile. When she shows me around the basement, she is calm. Every once in a while she laughs, although she has few reasons for joy. Her husband died during the war, she is left on her own. ‘His heart gave out,’ she says. ‘But you have to carry on somehow.’

The following nights will bring more of the same – destruction and death. Iryna and Olena will nevertheless continue to emerge from their basements at dawn and work tirelessly to bring their surroundings back to life. And they will carry on, until they lose hope that some day the dawn will bring them joy.

Curiosity (almost) kills the cat

I am met at Alina’s by a camouflage pickup truck with the markings of the Donbas-Ukraine battalion. It takes me to the base. There, military units are already preparing to take up their positions. I am assigned to ‘Tomcat,’ a maniacal soldier who has been thoroughly battle-tested since the start of the war. He has been wounded several times, once critically. He jokes that his body contains so much shrapnel that he will never be able to pass through a metal detector again. His foot and leg injuries make it almost impossible for him to walk in shoes without intense pain, so he only wears them when it’s really necessary; otherwise he goes around in slippers. Even – surprisingly effectively – during battle. Slippers have become his hallmark. He is in his thirties, with a dark complexion, a buzz cut, and the face of an imp. He is slightly stooped and moves nimbly, as befits a cat. We met when he was leading military exercises at one of the bases. After they had wrapped up, he came up to me and said, ‘Come with me later. I have a lot of plastic explosives left over. There will be quite a bang!’

I had nothing better to do, so I agreed. We went out to the forest clearing that served as a firing range. Tomcat scooped out a hole in the dirt, laid the explosives, and set the detonator. ‘Take cover!’ he called out.

I threw myself to the ground; he ran in those rubber slippers and slid up over a ridge. There was a loud explosion. The smoke rose up and the dirt spattered, falling on my face.

‘How was that?’ He rose from the ground, visibly excited. ‘Great,’ I said, uncertainly.

***

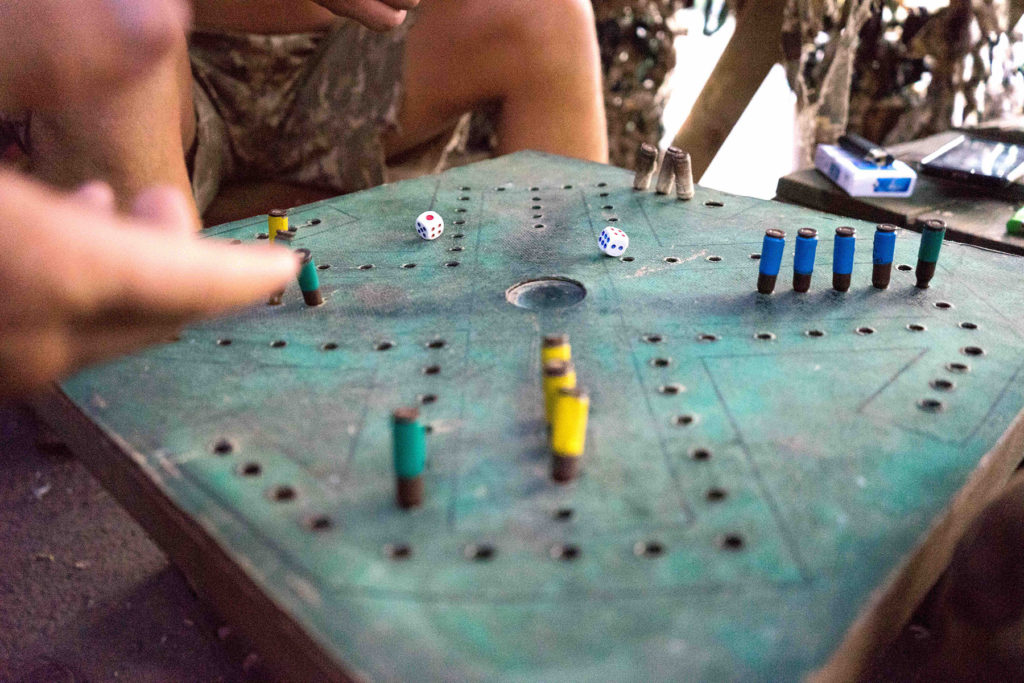

Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

This time, we are not engaged in any kind of exercise. I am accompanying Tomcat’s unit, which has been tasked with preventing the potential entry of hostile agents into the city. Sometimes the defences fail, allowing enemy fighters to penetrate fairly far into Marinka. If they are not stopped, they can inflict significant damage by attacking soldiers from the rear. That is why specially designated groups like Tomcat’s are sent out in the late afternoon.

Besides me and ‘Wildling,’ the driver, twelve men pile into the pickup. Five in the cab, the rest crammed into the truck bed almost on top of one another. They are all armed; I just have my camera. The truck takes us to the eastern part of town. We speed along the asphalt and then navigate potholes in the hard-packed dirt road to the tune of a song by the band Okean Elzy. They are singing about love and betrayal, but in wartime even pop songs take on new meaning. ‘Shoot! Tell me, why are you afraid / To take this last step? […] / Go on, pull the trigger.’

Chayka, a fighter with the Donbas-Ukraine battalion. Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

Wildling drops us off not far from our destination. Before we enter the abandoned building, the soldiers carry out some routine procedures: they check the gates, the doors, the rooms, the surrounding area. They are convinced that some of the city’s inhabitants are actively supporting the rebels, so it is possible that someone set a booby trap during the unit’s absence. They don’t find anything, so we head inside. There they all take up their usual positions – on the couch, on the chair, on the bed. Only I sit down hesitantly on the floor. Tomcat tells me it’s better to sit on a chair so I don’t catch cold. I do as he says, but then he decides that perhaps it’s not a good idea after all – my head is positioned between two windows and I might get hit by shrapnel. So I grab a pillow and sit back down on the ground.

We guzzle coffee and energy drinks and eat cookies. The soldiers drain the cans as if they had had nothing to drink since morning. They want to work themselves up before the coming skirmish. They are waiting for the situation to develop. When sounds of fighting begin to emanate from the east, they know that the rebel commandos are slowly approaching. Tomcat lifts his head with a jolt, ponders a moment, listens, and then calls out: ‘Take your positions!’

Everyone musters swiftly. In just two or three minutes we are already outside. I am supposed to stand by the entrance to the basement so I can hide quickly if things go south. Guns are firing and grenades are flying, but you can’t really see much. It is late summer and the terrain is overgrown; it’s a bit like battling bushes. But the bushes are shooting at us, and they’re coming very close. Judging by the sound, they are hitting the walls. Our situation is not very comfortable – the rebels are hiding in a gully, and it’s difficult to make them out. More rounds are discharged, but it’s hard to gauge the result. The second unit reports that someone in civilian clothing is running around in their sights and they don’t know what to do with him. Tomcat directs them to detain him. In the meantime, command is ordering a change of position to ensure the safety of the remaining units.

‘We’ll see what kind of civilian is hanging around in the middle of a battle,’ Tomcat comments sarcastically. He is aloof towards the locals.

We exit the building and run single file. We take cover behind some houses and are met by the second unit, the detained man in tow. He is running around with his hands raised. He is frightened, jabbering unintelligibly. He looks to be over forty. He has rubber slippers on his feet, he is wearing shorts and a striped polo shirt that stretches over his protruding belly. The soldiers tell him to lie down on the ground. A bullet strikes nearby and I can feel the earth shaking. The guy grows even more frightened and asks if he can stay with us.

‘What, so that we can all die together?’ says one of the soldiers, Foxtrot, who is standing by a gate that leads to one of the residential buildings. ‘I am not afraid of death,’ the man says, gathering the last of his courage, but he is still lying prone, lifting his head only slightly.

The gate behind Foxtrot opens. ‘Your back! Your back!’ another soldier yells. Foxtrot turns around abruptly, his safety disengaged. An older man comes out from behind the gate.

Whenever a battle starts, there is always someone who wants to see what’s going on. He will go out into the road in the midst of an artillery bombardment or even during a firefight, just to watch. Sometimes entire families come out to have a look. They don’t always understand the need to hide. Sometimes they come out at night, when limited visibility places even more strain on the soldiers and a single wrong move can make someone pull the trigger. Civilians often repeat, ‘Whatever will be, will be.’ They stare at combat as if they were watching reality TV. (Donbas residents often list the difficulty of accessing television programming as one of their biggest problems, despite the proliferation of devastation, fear, and tragedy). Civilian casualties are not always the result of evil intentions on the part of the combatants. Sometimes they are caused by heedlessness, bravado or unchecked curiosity. War overpowers people completely. In wartime, there are tragic consequences to the defiance induced by constraints on people’s liberty and their failure to follow orders.

‘Piss off, grandpa!’ yells Foxtrot, fired up on adrenaline.

Grasping that venturing out was not a good idea, the old man closes the gate and we hear him heading home. For a fraction of a second, I could already see his bullet-riddled body in my mind’s eye, lying on the ground in a pool of blood, a grimace frozen on his face after Foxtrot had reflexively pulled the trigger in a moment of perceived danger. Fortunately he had kept his cool.

The detained man is still lying on the ground. Every now and then he begins babbling. I finally grasp that he is hardly any kind of rebel fighter. He got boozed up, he bugged out, he began wandering around the courtyard. It was sheer bad luck that he wandered into the soldiers’ sights – as Foxtrot puts it, ‘posing for a portrait.’ They very nearly killed him.

Something is roiling inside me – how can they drag this frightened, inebriated man along and have him lie on the ground in the middle of a battle? They are unnecessarily exposing both him and themselves to danger, because having a civilian in tow renders almost any manoeuvre practically impossible. We cannot move until Wildling comes to get him. At the same time, I can’t really blame the soldiers for detaining him. What else could they do? Let him run around in the midst of a firefight? Then the likelihood of him getting killed would be much higher.

The exchange of fire continues. We are creeping along in a crouch because there are bullets flying just above the fence. We are waiting for Wildling to come get the detainee and take him back to base to figure out who he is. The man doesn’t have any documents with him, and it’s difficult to get any information out of him under the present circumstances.

The pickup truck arrives shortly. Tomcat quickly explains what happened. ‘Wilding, take this degenerate. Check out who he is.’

Moving shakily, the terrified civilian tries to climb into the truck bed.

‘On the back seat, bitch.’

‘Please, let me go,’ he says, but without conviction. When they put him in the pickup, he begins to cry out in fear, ‘Slava Ukraini!’ (‘Glory to Ukraine!’) He hopes that this sudden display of pro-Ukrainian sentiment will inspire trust among the enraged soldiers.

That day the rebels did try to break through the defences and infiltrate the city. They were held back, and it turned out this man had nothing to do with them. He was not released until the next day, because it would have been too dangerous for him to go home at night. The soldiers claim that they didn’t mistreat him while he was detained. It turned out he was just a local drunk.

Photo: Paweł Pieniążek

Published 6 September 2017

Original in Polish

Translated by

Marysia Blackwood

First published by Eurozine

© Paweł Pieniążek / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

On top of housing, work and schooling, Ukrainian refugees with HIV face an additional, urgent difficulty: how to access the antiretroviral medicines they need to suppress the virus. In Poland, they face a particular stigma, causing many HIV positive refugees to conceal their health status.

Growing numbers of Russians are fleeing the stifling atmosphere that has settled across the country’s political and cultural realms. Nowhere is this more tangible than in the world of popular music – once a shared cultural space between the two nations, now just another battleground in Russia’s war against Ukraine.