Istanbul, Liverpool, Marseille and Naples: four European harbour cities, alike in many ways, different in many others. Marseille, the oldest city in France, was founded by Greek sailors from Phocaea (modern day Foca, in Turkey’s Izmir province) around 600 BC; Naples and Istanbul are also over 2000 years old and were important cities during the Roman Empire. Liverpool, by contrast, is a young city and until recently was very small: in 1700, its population numbered approximately 5000. Liverpool experienced rapid growth in the nineteenth century, its 78,000 inhabitants in 1801 increasing to 685,000 a century later. As a result, it is less historically dense and multi-layered, particularly in comparison with Naples and Istanbul, which had very complex functions as capitals of large states and – in Istanbul’s case – of an empire. The borough of Liverpool was founded by King John in 1207 as “a safe port of embarkation to serve Ireland”.

Liverpool does not have the more subterranean memory of a longue durée characterizing the other three cities; historically, it was more focused on its harbour whereas Istanbul, for example, was not just a port but also an important military and administrative centre, a place of pleasure, culture and meditation with summer palaces, gardens, fountains, bazaars and mosques. Liverpool’s role was based more on functions around maritime trade – finance, insurance, shipping and legal services.

Nevertheless, all four cities share a nostalgia for the past glories of a Golden Age. They all suffered decline and a loss of importance after the emergence of modern nation states and the consolidation of national capitals. Liverpool lost most of its advanced service functions to London and other UK cities from the late nineteenth onwards; Naples lost ground as a legal and administrative centre after the incorporation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (of which it was the capital) into the Italian state in the late 1860s. There are signs in all four cities of a yearning for lost grandeur, a kind of mourning for what cannot be retrieved, and an internalised feeling of resignation, and sometimes resentment, towards the uncontrollable external forces that have put an end to, or at least eroded, the city’s greatness.

Talking of Istanbul, Orhan Pamuk has described this nostalgia as hüzün – a melancholy that “teaches endurance in times of poverty and deprivation. […] It allows the people of Istanbul to think of defeat and poverty not as a historical endpoint, but as an honourable beginning fixed long before they were born.” This state of mind, which is shared among the community and borne with pride, “is ultimately as life-affirming as it is negating.” This fatalistic tolerance is evident in the local humour – perceptible in the popularity of “investing in the miraculous”, through lotteries, gambling or the Neapolitan art of la smorfia – translating signs in dreams into lucky numbers.

These cities also have a distinctive social structure, retaining as they do a far stronger pre-industrial, plebeian milieu – defined by historians as le menu people – made up of artisans, small traders, bazaar and market stallholders. Such a milieu is defined by face-to-face contact, direct communication, neighbourly relations and close social bonds. Even where the local economy has undergone seismic changes in scale of operations and ownership, this distinctive local flavour has nevertheless been retained in some shape or form, even if only in popular memory.

Hybrid culture

Rising between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara, Istanbul, formerly Constantinople, experienced a cosmopolitan flowering during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the city had a diverse mix of nationalities and ethnicities – Greeks, Jews, Armenians and Tziganes. Although the Turkish population predominated, there were Christian and Jewish districts and outlying villages along the Bosphorus and Catholicism was freely practised alongside Islam. Galata, the western port on the other side of the Golden Horn, harboured cabarets among the shops and warehouses where Jewish commission agents did business. Wealthy Italian and Greek merchants wore Turkish clothes and lived in large, French-style houses; the French Ambassador resided in the hills above, in the Vines of Pera. Scutari (today’s Üsküdar), a Turkish town on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, was the caravan terminus of Constantinople for eastwards traffic.

However, since the beginning of the twentieth century and the end of the Ottoman empire, Istanbul has turned inward no longer refreshed and stimulated by the influx of new cultures. As Pamuk writes: “When the empire fell, the new republic while certain of its purpose was unsure of its identity; the only way forward, its founders thought, was to foster a new concept of Turkishness, and this meant a certain “cordon sanitaire” from the rest of the world. It put an end to the grand polyglot, multicultural Istanbul of the imperial age; the city stagnated, emptied itself out, and became a monotonous, monolingual town in black and white.”

As part of an urban renewal plan for Istanbul European Capital of Culture 2010, Istanbul’s Fatih municipality destroyed Sulukule, a historic Roma district bordering the fifth century walls of the city near the Topkapi Palace. It was composed of low-lying classic Ottoman houses typical of the Golden Age of Suleiman – made of “wood, ‘earthen walls’ and half-baked bricks, their facades daubed in pastel colours, pale blue, pink and yellow”.

Except for six homes under legal dispute, in April and May 2009 the Roma houses were razed to the ground and replaced with more expensive houses, shops and facilities for tourists. The 3,400 residents were transferred to other parts of the city, often far from the city centre. The Roma’s roots in the district went back five hundred years: traditionally they had made a living as street hawkers, shoemakers and, above all, as musicians and dancers. Until the early 1990s, the area was famed for its lively music and nightlife that drew in many visitors. When the government shut down the entertainment spots on the grounds of public order, the area went into serious economic and social decline – with crumbling houses, high unemployment and the usual signs of urban decay: drugs and prostitution. The impoverished residents finally submitted to urban renewal imposed from above. In many cases this meant splitting up extended families and destroying people’s outdoor way of life. As Mehmet Asim Hallac, a community leader involved in Sulukule Platform, which mobilised against the project, expressed it: “This is a street culture and the people can’t adapt to modern city buildings or blocks of flats. They spend most of their time outside their homes. They eat and drink outdoors and only go inside for proper family meals or to sleep at nights. Disrupt this with a modern lifestyle and they will be unable to breathe.”

Commenting on the Sulukule case, as well as on a similar gentrification project in the other central district of Beyoglu, Asu Aksoy writes: “In the new political economy of globalizing Istanbul, as more and more city spaces are handed over to developers to be turned into money-making assets […] historic neighbourhoods, with their architectural heritage, their multi-layered meanings, their cultural and historic references, and their present day social functions, are all made readily available for erasure.”

Liverpool’s cosmopolitan tradition was embedded in the waterfront – “a diaspora space, a contact zone between different ethnic groups: transients, sojourners and settlers with differing needs and intentions. […] With the opening up of new markets after the abolition of the slave trade, ethnic diversity became increasingly apparent: significant numbers of Kru (from West Africa), Lascar (from the Indian sub-continent), Chinese and other seafaring communities within and beyond the ‘black Atlantic’ were drawn to the port and its open ‘sailortown’ culture, often more than temporarily”.

African American sailors, the descendants of slaves, were increasingly drawn to the port along with poor Irish, Jewish and other transient migrants who in passing through found themselves stranded. So the port area became a “‘syncretic’ fusion between Irish and black culture” and the area around Frederick St. successively a home to Africans, Chinese cooks, stewards and deckhands, and temporarily to Filipinos Born in Mauritius, the son of a Master Mariner, the great-grandfather of Liverpool poet Adrian Henri was one of those who made a stopover during his world voyage and, struck by the similarity to Marseille of the city’s thriving port and the bustle, vitality and social mix on its streets, decided to stay.

Although one strand of cosmopolitanism linked to the Empire came to be mythologized in the city as a false alibi against racism, a “vernacular” form of cosmopolitanism has been lived out in everyday life, leaving its mark in high rates of intermarriage and inter-ethnic relationships in the heterogeneous black and mixed race Liverpudlian communities. Liverpool has lost something of its cosmopolitan flavour since the end of the nineteenth century and particularly since its port declined after World War II. Historically, however, its most informal areas with the greatest social creativity have been the ethnically mixed ones. In the late 1950s and ’60s, the Toxteth district harboured the coffee bars, basement jazz clubs, gay bars and West Indian shabeens where the would-be musicians, poets and artists lived and socialised. The Mersey scene took off because of its exposure to diverse cultural influences, as Paul McCartney testifies:

There were always sailors coming in with records from America, blues records from New Orleans. And you could hear so many different ethnic sounds: African music, maybe or calypso, via the Liverpool Caribbean community, which I think was the oldest in England. There was a massive amount of music to be heard. So with all these influences, from your home, the radio, the sailors and the immigrants, Liverpool was a huge melting pot of music. And we took what we liked from all that.

However, the main beneficiaries were young, white working class men who had been to art school or university. The greater freedom to experiment with different forms of music, poetry and drugs in Liverpool arose, in part, from the authorities’ laissez-faire attitude to areas in which the black community was concentrated. It left them alone as long as such activities did not spill over into more “respectable” areas. This came to be a defining feature of British multiculturalism, although drugs raids later became frequent, in the turf wars between rival clubs.

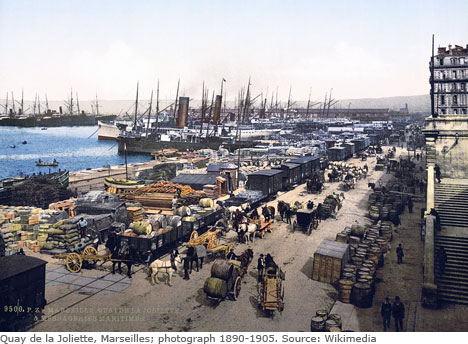

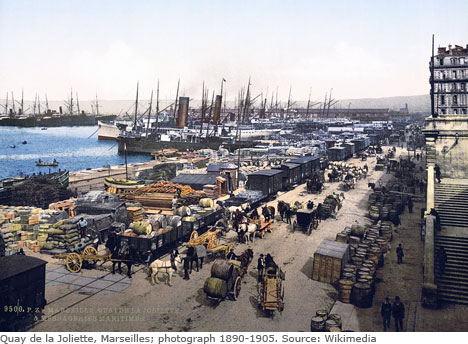

The population of Marseille is more ethnically mixed and cosmopolitan than that of the other three cities. There are older layers of immigrants who have become French citizens. The elites are drawn from a very diverse mix of people of varied origin, including white French, Lebanese, Senegalese, Algerians, Jews, Tunisians, Armenians, Italians, Spaniards, Corsicans and others. Many of the central districts of Marseille are ethnically highly mixed whereas in Naples, such mixing is a recent, though increasing trend. Marseille has historically been a cosmopolitan city – described disparagingly by writer and activist Flora Tristan in the mid-nineteenth century as “a rabble made up of all nations. […] An Italian, a Greek, a Turk, an African and all those from the Levantine coast”. Political exiles also enhanced the city’s composition: Russian émigrés, Armenians fleeing Turkey, and Spanish refugees from the Civil War in the early twentieth century; Maghrébins and Italian anti-fascists in the interwar period; Africans, more generally, after World War II; and then pieds noirs, after Algerian independence in 1962. A mosaic of 111 quartiers, Marseille’s diversity is very marked in the central districts round the port – Le Panier, la rue des Chapeliers, Belsunce, Grand Carmes, Noailles and Opera – where 80 per cent of Maghrébin immigrants live, comprising a sixth of the population.

Until the 1990s, the port of Marseille was renowned as a cosmopolitan hive, attracting weekend visitors from other quartiers to its mix of Maghrébin and French shops and stalls, festivals and diverse cultural events on offer. It also attracted a consistent flow of Algerian visitors – 35,000 in a good week in the 1980s, looking to provide household goods, wedding gifts and trousseaux for their families or village. The Mahgrébin souk grew to more than 500 stalls and boutiques, with a turnover of over three billion francs a year; and the French-owned department stores also benefited, with 50-90 per cent of their custom supplied by foreign visitors. But, due to the city council’s increasing neglect of traffic, pollution, public hygiene and cultural facilities, drugs and prostitution crept into the area and its reputation declined, acquiring a negative image as a dangerous place invaded by Arabs, a casbah that was no longer French. This was all the more remarkable since many of the stallholders were pied noir Jews, while all the wholesalers and half the retailers had French nationality.

The Maghrébin character of the area came under attack during the subsequent wave of urban renewal due to mobilisation by the Front National for the expulsion of immigrants while the Chamber of Commerce claimed: “a policy of renewal of quality housing for occupants with high purchasing power is necessary to revitalise commercial activity in the city centre” So an explicit policy of la reconquête de Belsunce was put forward with the support of the Front National. The city council, with its Socialist Party majority, adopted a policy of reéquilibrage sociologique that encouraged white Marseillais to move back to the city centre, in part by relocating city council offices, university buildings, a library and student housing there. Under this academic euphemism, the council pursued a racial gentrification strategy. The urban renewal programme of 1987-90 cleaned up the area, but the Arab market was moved further out; a key street – rue Saint Férreol – was pedestrianized and chain retailers were encouraged to return from the periphery. These re-conquered the high street of Belsunce, leaving the fragile economy of the souk to survive only in the side streets. This policy produced a large number of empty properties, as Maghrébins were forced out and white Marseillais returned only slowly and in small numbers. The failure to draw back white Marseillais meant that Mahgrébin families gained access to social housing (HLM) in part of Belsunce-La Butte de Carmes; gradually, Maghrébin commerce – Oriental patisseries, fringe boutiques, jewellers and mobile phone operators – has re-emerged. Wholesale stores have tended to change hands, from North African Jews to Chinese traders.

Naples’ cosmopolitan tradition has left linguistic traces in place names in the Quartieri Spagnoli, the Via Toledo and the Via Medina and is equally evident in the openness to newcomers, among whom the Sri Lankan community is the largest group, alongside the second biggest Albanian diaspora in Italy. A growing Chinese community has established a strong presence in the popular Ferrovia quarter around the central station in Piazza Garibaldi, where its strength in retailing and wholesale has provoked rivalry and racism. However, the market has African, East European and Neapolitan stalls and acts as a meeting place for Maghrébins, white Neapolitans, Senegalese, Eritreans, Ethiopians, Nigerians, Poles and Ukrainians and locals, including university students. Whereas Naples was traditionally associated with the transient migration of people passing through via the port, the new global migration tends to be more settled and locally rooted. The part of the Ferrovia quarter known as Forcella now hosts two mosques, an indication of the city’s changing cultural landscape.

The city shows a continuing capacity to welcome and absorb its very varied and culturally diverse range of foreigners by “participatory belonging”, manifest for example in the habit of giving foreign workers a Neapolitan first name as a sign of endearment or acceptance – as Coppola notes, “Naples and its hinterland are full of Gennaris and Pasqualis born in Albania, Poland, Sri Lanka or Central Africa, names reformulated according to assonance or out of sympathy”.

After the earthquake in 1980, the Naples region underwent a sustained period of speculative reconstruction, illegal house-building and elevated highway construction that scarred the landscape and left people cut off from the city centre without social or cultural amenities. After 1993, following election of a leftwing mayor, an attempt was made to revive the city’s cosmopolitan tradition of openness both towards its residents living on the periphery and to foreign visitors. The City Council’s regulatory urban plan aimed to improve liveability in the city centre by pedestrianising some streets, recouping green open spaces and the seafront, and connecting outlying areas to the historical centre. This period of renewal also encouraged new initiatives from cultural associations such as the Associazione Festival Centro Antico and Neapolis 2000, who for two years organised guided tours, opened up monuments in the evenings, and animated cultural heritage with concerts and performances. Neapolis 2000 – set up by the NGO Lega Ambiente (Environmental League) – is dedicated to “unity in diversity”, understood “not through the lens of coexistence but that of a truly multiethnic society”. The organization has had difficulty integrating this vision into its environmental campaigning.

However, the emergence of the Associazione 3 febbraio – set up in Piazza Garibaldi on 3rd February 1996 – expressed the desire of local residents to intervene actively in the Ferrovia quarter, to demand investment from the government and, as its manifesto clearly states, to “fight for the right of people of different ethnic groups and cultures to meet, live together and positively influence one another”. In its more than ten years of existence, it has acted as an aggregating force, bringing together immigrant groups (including clandestine migrants who operate as unlicensed street traders) and local white Neapolitans, to counter the neighbourhood’s economic demise and potential for racism. It has won wide support, including that of long established restaurateurs and the proprietor of the largest hotel, who see their livelihoods as bound up with the vitality and diversity of the area. The expressly egalitarian and libertarian values of Associazione 3 febbraio are based on mutual respect, self-help and active citizenship: “Solidarity means helping each other, uniting, being brothers (sic), not accepting hierarchies between people as in welfare dependency. […] Everyone must be a protagonist, an active subject who supports activities, and not an object or mere recipient” (see www.a3f.org).

Informal economies

Informality thrives in certain conditions – where the state is either weak or entirely absent. This vacuum opens a space for forms of solidarity – such as sharing scarce resources within a group, or being open to outsiders – as well as for exploitation of the weakest through gang violence. Necessity being the mother of invention, such conditions act as a spur to improvisation – to living on one’s wits. Yet this inventive streak is often stifled by a lack of resources, or distorted to serve lucrative and dangerous ends.

Traditions of informality in port cities are related to the casual nature of labour in ports and to tentative, faltering industrialisation. In comparison with industrial cities, seaports are less regulated by clock time and characterised by a masculine culture of individualism and resistance to rules, which is fertile ground for informal economic and social relations. Casual employment has also shaped local identity, by forcing dockers and others in allied trades to stick together during long periods of unemployment and precarious work or protracted strikes. This has fostered solidarity among workers and their families. For example, the longest strike in the history of industrial relations in Britain was the unsuccessful Liverpool dockers’ strike, from September 1995 to February 1998. The lack of secure employment has bred a fatalist acceptance of the inevitability of hard times and a tendency to devise improvised solutions to gain a livelihood – expressed in Naples by the term arrangiarsi – to get by – and in Liverpool by “ducking and diving”.

This resilient imagination is also visible in the myriad of invented street trades and professions, almost unique to Naples, which are often characterised by recycling and repair – the mullecaro, for example, who used to collect cake crumbs from patisseries and sell them in paper cones (known as cuppetielle) to children in the street; the saponaro, small-scale rag and bone merchants who used to exchange home-made soap for old clothes; the mpagliasegge or woven rush upholsterers; and trades linked to fortune-telling, tarot, soothsaying and numerology. Although many of these trades are disappearing, some still survive, particularly in the Spanish Quarters of the city centre.

In all four cities, port trade before containerisation offered ample opportunities for pilfering goods, which were then sold in semi-legal street markets, pubs or private houses. This built on a long tradition of smuggling. The trade in contraband and stolen goods was tolerated to a large extent both by citizens and the authorities because it was seen as a way of supplementing the precarious income of working class families, and thus countered potential outbreaks of protest and social instability.

The Piazza Garibaldi area by the central railway station in Naples, traditionally the first point of entry for immigrants, has been a centre of smuggling and illegal trades since World War II. In the 1940s and 50s it became the key place in Naples for commerce in new consumer goods – radios, white goods, toys, watches – all of which were smuggled and controlled by Italian Neapolitans: a situation the novelist, Ermanno Rea ironically termed “the daily comedy of tolerated illegality”. The street traders still operating in Via Mancini are now mainly Maghrébins, who sell cheap jewellery and bric-a-brac, while the Chinese run all the shops in the area, selling mainly clothing and household goods.

The section of the quarter popularly known as Forcella is today regarded as the most dangerous part of town. Although traditionally associated with shootings and organised crime, it has now become the dormitory district for the most marginalised of the marginalised and desperate, and is run by gangsters who demand extortionate rents from the Roma, Somalians, Nigerians, Moroccans and Brazilians who are forced to live there. Due to its high concentration of clandestine migrants and their exploitation by criminal gangs, this area is currently the part of Naples undergoing the most rapid change in social morphology. It is difficult to see who controls the distribution of territory and allocation of street vendors’ “pitches”. Forcella is a microcosm of a dystopian future for the city, with the spectre of governance left entirely in the hands of organised crime, and the threat of domination by the local mafia – the Camorra – spreading to the heart of the city. Nevertheless, these four cities share a distinctive “moral economy”, born of informality. In Naples, it is still better to live in the poverty of the bassi – the overcrowded tenement basements in the Mercato-Pendino inner city districts – than in the notorious peripheral housing estate of Scampia in the northeast of the city, to which low-income residents displaced by the 1980 earthquake were moved. Although many residents in Mercato-Pendino are stuck in sub-standard housing, strong social networks and solidarity persist in a vibrant, ethnic cultural and social mix, where opportunities exist for casual work in commercial and personal services, wholesale and retail trade, and some artisan trades are maintained in niche economies. Even though the inhabitants live off combined incomes from different jobs, mostly cash-in-hand in the black economy, they are not primarily tied up in crime. Scampia, by contrast, suffers not only the worst levels of unemployment and lack of qualifications and skills in Naples, but also from social isolation and a lack of social and cultural diversity Consequently, the neighbourhood has little of the organisational capacity or social resilience necessary to build alternatives to dependency on the hugely lucrative drugs market dominated by the Camorra.

Where forms of solidarity are found within communities, the boundaries are often drawn tight and mark an exploitative attitude to the outside world. This can make the experience of being an outsider, for example, a tourist or clandestine migrant, unpleasant or even dangerous: outsiders can be treated as prey, especially in Naples and Istanbul. These are contexts in which criminal gangs can intervene to exact a price for becoming an insider or acquiring protection.

Improvised solutions to earning a living have become increasingly unviable due to the crisis of artisan trades all over Europe and developments specific to each city, such as the collapse of cigarette smuggling in Naples, when contraband trades shifted to Albania and Montenegro in the wake of wars in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The employment crisis has been exacerbated by deindustrialisation, which hit Naples, Marseille and Liverpool especially hard, as they had been relatively secondary industrial centres.

In parallel, criminal organisations like the Camorra of Campania, the region of which Naples is the capital, have grown stronger, more entrepreneurial and organised at global level, with a greater capacity to penetrate the formal economy and fill employment gaps. They operate in a wider range of fields, including property development, finance, waste disposal, leisure, tourism and the fashion industry, going well beyond the traditional sectors of drugs, prostitution, gambling, people trafficking and extortion, though the traditional hold in these areas has not let up – over 50 per cent of shops in the region pay protection money but in some peripheral districts and towns in Campania everyone pays.

In the Naples metropolitan region, the informal economy organised by international criminal gangs has become almost as big as the formal economy. It has penetrated manufacturing industries – dairy produce, papermaking, sugar refineries, ice-cream factories – and loan finance. It gives more preferential rates than the official banks and serves the insurance and saving needs of the lower middle class. With its tentacles spreading extraordinarily wide, the Camorra has even penetrated the cultural industries by promoting and marketing a form of Neapolitan popular music known as “neo-melodic”. In Liverpool or Marseille, meanwhile, the informal and criminal economies, though highly developed, have not reached global proportions or managed to penetrate the formal economy on this scale.

Social creativity

The multi-faceted social creativity of the four cities is manifest in many spheres: language, humour, theatre and story-telling, among others. The development of distinctive dialects like Scouse, Neapolitan and Marseillais has always been shaped by intercultural influences. Scouse, for example, emerged from the blend of Irish, Lancashire, Welsh, with some Scandinavian and possibly Chinese influences. The singularity of these dialects did not develop for purposes of class distinction, but rather to mark out the cities’ unique local character and differentiate them from their national culture, particularly from that of their respective capital city. In the case of Liverpool, the Beatles made cultural currency of working class accents, instead of aping “Oxford” or “Queen’s” English.

The economic structure of these cities has also shaped traditions of humour and entertainment. Long and intense periods of labour on board ship and in the docks were followed by periods of free time on land with enough accumulated income to indulge in hedonistic bursts of activity, for example in pubs, bars, brothels, dance halls and – in the three Mediterranean cities – restaurants.

One of the characteristics of local humour in port cities is quick wit, which has been related to the fast rhythm of dockers’ work and their need to win the trust rapidly of ever-changing crews. Certainly, insecure livelihoods have bred a kind of sardonic comedy in the face of economic and political adversity and defeat – manifest in Naples in the films of Totó and Massimo Troisi, whose humour was exacerbated in the 80s and 90s by “total disenchantment, which has by now turned into desperate irony […] an element that undoubtedly belongs to the ethos of the city”. In Liverpool, this comedy has a surreal twist (Belchem, 2000, 51): witness, for example, the humour of Alexei Sayle and the side-splitting, Radio Merseyside phone-in programme “Hold your Plums”. Similarly, Marseille’ grotesque and farcical comic tradition plays on the conviction that humour is “humanity’s only revenge for the absurdity of its condition”.

Theatre in the Mediterranean tends to be more physical, earthy and performative than text-based, reflecting the major historical influence of the griot tradition in African theatre. It also spills over from indoors onto the street – our four cities all share traditions of intense street festivity. A common metaphor for Naples is that of a teatro vivente – living theatre. Theatre in Naples has drawn inspiration from local social reality and in turn, its gestures and language have influenced popular expressiveness, resulting in dramatised social interaction in everyday life. As Neapolitan theatre and film director, Mario Martone has pointed out:

In Naples one finds a quantity of actors, and of a quality that cannot be found in any other part of Italy – of Shakespearean […] or Chekhovian proportions […]. Precisely because there exists in Naples a language, a great dramatic tradition, and a capacity to interpret that tradition that do not exist in other parts of Italy.

Even Liverpool, the northernmost city, with an unfavourable climate for outdoor activities, has an outdoor night-life, especially in the Rope Walks area, characterised by flamboyant attire, good-humoured, drunken singing and an overall atmosphere of street cabaret. However, a problematic aspect of theatricality and festivity in the four cities is that of the “professional” Neapolitans or Scousers or Marseillais, who enact a parody of local identity. As Martone observes, this involution is encouraged by the media’s promotion of an image of the locals, which is “captivating, banal and falsely endearing […] for it deprives the tradition of its conflict aspects and tragic content”.

Liverpool, Marseille and Naples in particular have an abundance of stories “from below” of the poor and marginalised, and prolific literary representations of the city as lowly, carnal or “base”. These have shaped the dominant urban narrative over long periods and hence, the internal and external image of the city. For example, the neighbourhoods around the old harbour of Marseille were portrayed until World War II as le grand lupanar, a place of vice, which reinforced the image of the city as “an infected wound and purulent sore on the supposedly virginal body of France”. In late nineteenth century Naples, Francesco Mastriani represented the backroom life of inner city districts in his novels of social realism, I vermi (The Worms) and I misteri di Napoli (The Mysteries of Naples), as did Matilde Serao in her Il ventre di Napoli (The Underbelly of Naples). These describe a city “dominated by the Camorra, exploitation and the uncertainty of employment and life, ravaged by cholera and waiting for […] a miracle that will solve everything. They depict […] an enclosed space that consists of storerooms, basement tenements, alleyways, small squares – the back passages and nether regions which never seem to see light and are a thousand miles away from the legendary Bay of Naples”.

Informal spaces

The lack of social stratification and rigid distinctions in informal spaces in the four cities produces a different, more open social geography. Since there is no formal bar to entry, such spaces allow people to meet more as equals despite differences in their respective civic and social status. Such informal spaces can be found in liminal areas, at the point of entry and confluence of different cultures (where the outsider and insider meet or overlap and where the transgressive jostles side by side with the respectable); or at the margins – to which the rejected, abandoned or discarded are banished.

Port cities are rich in informal spaces as their immediate threshold, the docks and port area, form a diasporic place of transience, mixing and settlement. The red light districts and sailors’ haunts mixed with an area of entertainment blur the distinction between high and low cultures. In Marseille, the absence of policies to regulate social contact in the city centre led to an overlap of opera and prostitution. The same lack of spatial segmentation and social distinction made possible the Maghrébin settlement in areas around the old city-centre port. Repeated attempts over the last twenty-five years to whitewash the city centre and segment the space have largely failed. In Liverpool the pubs around the port played an important role, not just for sailors coming off ship but for aspiring entertainers, who found a ready-made audience in the area’s numerous bars; while the shabeens and secret dives in Liverpool 8, the main area of black settlement in the city, gave birth to the first “Mersey scene”. At the start of the post-Punk scene, in the late 1970s and early 80s, gay clubs were essential for the birth of new Mersey Beat, as they were more open to new trends from America and a seedbed of new dance music. The myriad of decaying warehouses opened up opportunities for the launch of new clubs like Eric’s in 1976 and, in the 90s, the hugely successful Cream.

Many dead or decaying spaces – abandoned factories, warehouses and wastelands – have been retrieved thanks to artists’ initiatives to create crossover spaces that offer a mixture of mass, popular and sub cultures and live, electronic and digital art forms, with the aim of attracting the deprived and working-class and other very diverse communities. The Rope Walks area of Liverpool – so named because rope-makers who produced rope for the ships used to stretch and twist them along these straight narrow streets that run down towards the docks – was colonised by small cultural entrepreneurs, many of whom converted basements and even churches into clubs, bars and cafés. “Love Liverpool”, a project set up by Jayne Casey, former lead singer of 1970s Liverpool punk band “Big in Japan”, and co-founder of Cream nightclub, took over a piece of derelict land in Jamaica Street in 2006 and transformed it into an artists’ quarter with studios and live venues, the “Independent District”. When the Picket Club reopened in the centre of the designated area two years ago, Casey declared it “a significant moment of opportunity for a whole new generation of musicians and independent music promoters who plan to make the Picket and the Independent District their own”.

In Marseille, the Friche La Belle de Mai has reanimated the derelict tobacco factories where Gitanes and Gauloises used to be produced, to the north east of the city centre, in an area with about 30 per cent unemployment. Covering 40,000 square metres, it brings together musical associations, recording studios, creative writing workshops, sound and voice workshops and studio space for theatre, architecture and sculpture. The space also includes a local radio station, Radio Grenouille, a newspaper and a restaurant.

It was the brainchild of Christian Poitevin, a publisher, media man and key intellectual in charge of culture in Mayor Vigouroux’s cabinet. Although the Friche was envisaged as “neither institutional nor fringe” but somewhere in between, it is largely funded by Marseille city council. Under its director, Philippe Foulquié, it has developed as a place of métissage between different genres and media, between high-tech audio-visual and sub-cultures and between people of different cultural and social backgrounds. It was conceived as a laboratory where artists could come together to swap experiences, experiment and produce new work and public performances during artistic residencies, and also collaborate and co-produce with external organisations.

Ferdinand Richard, a co-founder of the Friche and the association AMI (Aides aux Musiques Innovatrices – Assistance for Innovative Music) has sought to combine public and private, offering free training to disaffected young people from deprived neighbourhoods as a means of facilitating their access to the music business, giving them time to develop, experiment and attain a high level artistically while also developing promotion outlets, publicity and private sponsorship. Ami has embedded a lively hybrid music scene in Marseille thanks to its label and record shop, Stupeur et Trompette, weekly concerts by musicians on tour, monthly hip hop and urban music concerts direct usine – direct from the factory – that follow on from the workshops, and the success of bands like the rap formation, Iam and the Provencal reggae-ragga-dub group, Massalia Sound System.

AMI has extended into a truly international network via a series of cultural exchanges and festivals involving cities in the Maghreb, Central and West Africa, the Arab world and Far East, each of which runs for three years, with two annual sessions in each city. With its festival, MIMI (International Movement for Innovative Musics), held for the first fifteen years in Arles, it established a reputation for avant-garde, experimental cross-over music. In 2001 MIMI relocated, retrieving a place in the Frioul archipelago used in the past to quarantine people, ever since the outbreak of a plague epidemic in the seventeenth century. Now, instead of isolating people from contact, it brings them together for an annual, open-air summer event. The MIMI festival has also developed into a series: a second edition, MIMI-NOR, has taken place every spring since 2002 in Narian-Mar in northern Russia; and a third edition, MIMI-SUD, since 2003 in Kinshasa in the Congo Republic.

Naples’ old industrial areas to the east of the city, including Ponticelli and Poggioreale and the degraded zones around Vesuvius are the home-base of Napoliest (East Naples), a creative research group comprising artists, designers, craftsmen and communications professionals who form “part of the informal economy”. As one of its founders Danilo Capasso explains, it began, “with a will to improve the livability of Naples, born of the lack of urban and social life-quality, and the lack of an economic platform. […] There is nobody and nothing fuelling the economy from the bottom in these areas. And that’s where we are starting from: from the bottom, on our own, with our own means of […] ‘sustainable persuasion’ we are laying the foundations for something that we would like to do in the future.” The strategic aim of the group is “to gather a group of professionals who can form a driving force, based in eastern Naples, that is strong enough to re-launch production and the economy of the city. We’d like to use the institutions and the arts to bypass the classical system of urban interventions.”

The group is building its capacity for strategic intervention by researching and mapping environmental degradation and urban transformation in the area and retrieving its rich archaeology and history. Via critical debate and artistic initiatives such as exhibitions, digital projects, video installations, documentary films and publications, it seeks to imagine an alternative urban fabric, contest the current uses and abuses of public space and propose creative, viable alternatives.

The dark side of informality

While informal spaces can offer places of reflection and quiet in the turmoil of the city, or act as places of inclusion where people can meet and socialise without commercial market pressures or fear of surveillance or intrusion by oppressive forces of the State, they are also a magnet for greedy developers, unscrupulous gangsters and corrupt politicians. More usually, local governments lack the strategic vision, political will and confidence to confront these forces and ally with the nascent, creative forces who have alternative visions of the city – as a more open, just, accessible, green and liveable place. The dark side of informality derives from both the weakness of the state and the lack of links between the planning authorities and the civic life of the community, its associations and democratic will. Naples offers a salutary reminder of this in the foothills of Vesuvius – where people have exploited the non-enforcement of planning regulations to build illegal settlements in eighteen municipalities. They managed this due to the absence of the state rather than the presence of the Camorra, for the area is considered too dangerous even for the latter. A weak and corrupt national state has failed to update the Italian Emergency Plan and take seriously the threat of a new catastrophe – despite experts’ opinion that, “there is a greater than 50 per cent chance of a major eruption each year now” – and local authorities in the area around the volcano have failed to intervene.

Such phenomena incite negative cultural responses and widespread cynicism about the capacity of the local state to deliver basic services: the separation of toxic and non-toxic waste by rubbish collection and disposal services in Campania, for example, sparked a national emergency in Italy in 2007/08. Such cases create a climate of semi-anarchy linked to the collapse of state authority and governance. In Naples, it has contributed to the general contempt for authority and flouting of social rules.

Theories and interpretations of informality and social creativity

A body of literature on the Mediterranean city, which applies to Istanbul, Marseille and Naples as well as to other cities, derives from philosophers of the Frankfurt School who sojourned in the Naples region in the 1920s. Walter Benjamin defined Naples as a “porous city”: one that absorbs diverse forms of life from different historical periods side by side, thereby creating what Ernst Bloch, writing in 1925, called “a multiverse”, which has no clear boundaries between public and private spheres. Bloch observed this in the way people interacted without inhibition or class barriers, or spontaneously joined in other people’s conversations in cafés or bars, or persisted in using their dialect and adapted it by absorbing new words and nuances.

For Massimo Cacciari, a philosopher and contemporary interpreter of this tradition, Naples and other Mediterranean cities are important because they form a bridge between north and south, and are open to “the Other”. Naples – the last European city and first Mediterranean city, a porous city – embodies the qualities required to play this role:

The porous city is a city in which nothing moves forward on straight lines, through ruptures. Herein lies the extraordinary modernity of these Mediterranean cities, which many stupid “modernists” have on the contrary, seen as their backward character which should be abandoned so they can become European! The form of these cities never develops through projects and plans thought out in advance. Nor does it consist solely of architecture and town planning. The Mediterranean city has characteristics of play, of openness, also on other levels…

Rather than suppressing differences, the porous city absorbs and thrives on them. Cacciari defines the contemporary challenge as being to combine the “porosity” of Naples with the characteristics of the rights-based State, of European legal rationality.

A whole philosophical school of il pensiero meridiano – Mediterranean thought – has grown up around Franco Cassano on this basis. It refutes the idea that Naples is backward. It reinterprets Pier Paolo Pasolini’s concept of Naples as a tribe shut up in the belly of a great city by the sea that will not surrender to modernity, and considers it rather as a source of resistance to capitalist commodification and instrumentalism. Above all, it draws inspiration from the thought of Albert Camus, seeing in the sea and the link to the land closer and more intimate relations between human beings and the natural environment, an awareness of human frailty and mortality, and also beauty. These more direct relations that give rise to solidarity on a human scale are at the idealised core of what these thinkers seek to retain – or retrieve – of the Mediterranean urban tradition.

Concepts of Mediterranean thought have also inspired the Marseille-based journal, La pensée de midi, edited by Thierry Fabre, which shares the view that the Mediterranean periphery of advanced capitalism embodies an alternative way of life or, at least, capacities that are not the product of backwardness or failed modernisation but a different form of modernisation. Among its virtues are an outdoor culture that acts as a source of resistance to passive home-based consumption and individualism and a livelier, more convivial public sphere.

The spur to setting up the journal was to provide a more enlightened response to the climate of fear and “the new obscurantism and obsession with identity” ushered in by 9/11. Rather than demonising Islam and the Islamic world, Fabre proposed engaging in dialogue with it and encouraging the modernising currents of Muslim thought. He sees Marseille, just as the Cassano school see Naples, as a “ville-pont et ville-frontière” – a bridge and a border town – between north and south, one that links both sides of the Mediterranean, and the Mediterranean with northern Europe. These themes, rather than those of clientelism, terrorism or the Islamic threat have inspired the Rencontres d’Averroès, an annual series of cultural initiatives (including roundtables, public lectures, films and concerts), created by Fabre in 2003, with support from the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

Policy initiatives

Local authorities and other stakeholders in all four cities are developing new, internationally oriented cultural strategies. To varying degrees, these policy initiatives build on informality, cosmopolitan traditions and social creativity as local cultural resources. The internationalism of these cultural policies is in part a response to the need (especially in Liverpool, Marseille and Naples) to develop new internationally significant economic activities and functions. Internationalism, intercultural dialogue and openness were important themes in the European Capital of Culture programmes in Liverpool in 2008 and in Istanbul in 2010. Marseille and Naples in 2013 will host flagship events whose key themes include Euro-Mediterranean cultural co-operation and the dialogue with Islamic countries. In 2008, the Marseille-Provence 2013 Association won the competition to host the 2013 European Capital of Culture while in 2007, and Naples City Council announced that it had been successful in its bid to host the 2013 Universal Forum of Cultures. The latter event was initiated by a Barcelona-based foundation, the Fundació Fòrum Universal de les Cultures (see www.fundacioforum.org), and was held in Barcelona itself in 2004, in Monterrey, Mexico, in 2007 and in Valparaíso, Chile, in 2010. The Forum focuses on the themes of cultural diversity, peace and sustainable development, by means of a cultural programme with a global reach, including exhibitions, performances, conferences and debates.

Bernard Latarjet, who was until 2011 Director General of the Marseille-Provence 2013 Association, highlights the fact that in Marseille there are no boundaries “between so-called ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture. In Marseille, words, situations and audiences derived from these two movements come together and mingle. Marseille is at the cutting edge of the renewal of art forms that speak to all, and most importantly to the young: circus arts, street and public performance arts, modern music of all kinds, digital arts, urban dance and poetry”. Liverpool, Istanbul and Naples have similarly inclusive and accessible cultural traditions. Latarjet adds that cultural dynamism and symbiosis in Marseille “is underpinned by a measured policy of welcome and aid which is extended to all creators who take over empty premises or wasteland, or who move from place to place with the aim of reaching out to previously sidelined audiences” (ibid.). The idea of the Ateliers de la Méditerranée is central to the cultural vision of Marseille-Provence 2013. The overall goal is to “make Marseille a permanent, long-term hub for intercultural Euro-Mediterranean dialogue”, by means of cultural projects that confront themes of cultural difference through exploring gastronomy, gender relations, memory, migration, exile and travel.

The idea of the role of Naples in Euro-Mediterranean cultural co-operation outlined in the city’s plans for the Universal Forum of Cultures 2013 is very similar to the Marseille-Provence 2013 vision (Comitato promotore Forum Universale delle Culture, n.d.). Naples’ policymakers have chosen as the central theme for the 2013 Forum “The memory of the future”, which “expresses the desire to consider Naples and the Forum as a temporal gateway between the past, present and future”.

Our four cities, however, face significant difficulties in implementing cultural policies and urban strategies focused on intercultural exchange, openness, informality and social creativity. In the case of Naples, important multicultural and intercultural projects have been developed in recent years. One such scheme (jointly initiated by the Provincial, Regional and City Councils) was the opening of the intercultural centre at Via Speranzella in the Spanish Quarters, in 2006. Yet these policies are crippled and limited in their effectiveness by the financial crisis of the city council, and the inability to counteract the power of the Camorra which infiltrates and, to a large extent, controls the economic activities of many immigrant communities – such as Chinese manufacture of fake goods and Ukrainian and Nigerian prostitution.

Liverpool has traditionally witnessed the co-existence of cosmopolitanism and institutional racism in access to services such as education and housing, together with deeply entrenched economic inequalities from which ethnic minorities in particular have suffered. There were some improvements from the mid-1990s on, given the political change to a new Liberal Democrat administration and the advent of the New Labour government in 1997, with housing renewal schemes in some of the ethnic minority areas like Toxteth, as well as the opening of new resource centres like the Novas Contemporary Urban Centre and the Kuumba Imani Millennium Centre. Nevertheless, ethnic minority residents of the city are still concentrated in relatively segregated areas, continue to suffer from multiple forms of social, economic and cultural exclusion and their presence has not been visible enough in the city’s cultural initiatives, including, arguably, the programme for European Capital of Culture 2008. Marseille is similar in many ways. The city is de facto very multicultural, in terms both of nationalities and faiths. However continuous delays since 1937 in the building of a city mosque and, more generally, the insufficient public visibility of the Arabic character of the city – evident, for example, in the lack of public spaces featuring Arabic art, architecture or music – indicate the general reluctance of the centre-right city council to embrace cultural diversity as a force for reshaping urban policy.

In the case of Istanbul, the cosmopolitan vocation of the city as a melting pot grew more difficult after the creation of the modern state and the shift of the capital to Ankara. On the one hand, this and the migration of peasants from Anatolia to the city led to the “Turkification” of Istanbul; on the other, Ankara remained persistently suspicious of Istanbul’s cosmopolitan character. To some extent, Istanbul has been able to counteract this due to its sheer economic might, geographic size and importance, and its symbolic power as the main centre of cultural industries in Turkey. The AKP government, led by Recep Tayyip Erdogan since 2003, has a vision of transforming Istanbul into one of the hubs of the global capitalist economy. As Aksoy notes, “this represents one contemporary variant of world-openness – the neo-liberal articulation”. The consequences of this economic development strategy are very problematic: “as global processes increasingly, and seemingly irreversibly, affect the daily life of the city’s fifteen million residents, older modes of urban living and established forms of public culture are damaged, if not devastated. […] Openness to global economic forces is associated with escalating social divisions, existential loss of control, and cultural vulnerability”

However, the four cities retain significant potential for future innovative cultural and urban policy-making. Whether such potential is realised or not depends on the strategic capacity of local governments, third sector organisations and socially engaged artists and intellectuals to mobilise experiments, ideas and practices founded on informality and social creativity, to become a force for civic renewal.