In Reset Modernity!, the Karlsruhe exhibition we just opened at ZKM, visitors are requested to follow a series of specific procedures to reset the instruments that allow them to find their way in this highly complex question: where is modernity heading and how can we orient ourselves through its metamorphosis? An excellent way, it seems to me, to consider the theme of this year’s lecture series, Zukunftswissen. Visitors were handed a precious little booklet that we call a “fieldbook” because they are invited, really, to play an active role in surveying the quickly transforming landscape. At the end of each procedure, a cryptic message is provided about a somewhat mysterious triangle. The curators seem to be arguing that once this triangle has been understood, things will become really much clearer. It is this claim which I would like to comment on by developing a bit what this triangle could mean and how it has been drawn.

Let me start from the world historical episode of 12 December 2015 when François Hollande, the French president, famously exclaimed “Vive la France, Vive les Nations Unies, Vive la planète!”, that is, “Long live the planet”. I am sure you remember the unanimous approval of the treaty concluding the Paris conference on climate, COP 21. If I say that it was a “world historical episode” it is not, assuredly, because any concrete policy came out of the conference. So far, it is the catastrophic “business as usual” trajectory along which all the signatories to the conference are quickly sliding. If I say it, it is because of the unprecedented diplomatic situation that it had created: for the first time in history, all one hundred and eighty-nine “sovereign” nations realized as never before that the world toward which they were happily moving, what I will call the Globe or the Global, has no terrestrial existence.

Let me explain: in advance of COP 21, each nation had been asked by the French secretariat to describe as clearly as possible their views of the future by writing a document called in characteristic United Nations jargon an “Intended Nationally Determined Contribution” or INDC. You would be wrong to take this as one of the many boring bureaucratic chores diplomats have to complete: the result of this exercise has been stunning. Why? Because when participants began to add up the wish lists of China, India, Brazil, Europe, Canada, the United States, Philippines, Ethiopia, etc., that is, how each sovereign state envisaged its development in the years 2030 or 2050, it became clear for all the other participants stuck in the same wood-beam hall in the Paris le Bourget exhibition centre, that there existed no credible planet capable of absorbing all of those wishes.

Photo: Brad MacDonald. Source:Flickr

You will tell me that such a dire situation has been clear since the early days of ecological consciousness; and surely you will remind me that there exist many groups of scholars calculating the number of additional planets necessary for the development of all 8 billion humans – from 2 to 5 virtual planets depending on calculations and expected level of development – when we have only one planet. Yes, for sure, but the measure of such a reality has never been taken up inside a diplomatic assembly, the United Nations, where for the last 70 years the main idea has been that there was one common horizon for all nations, what can be called the horizon of modernization toward which they could not but necessarily converge into one Global Globe. More importantly, in early December, the very definition of sovereignty has meant that any decision to develop one way or another is not any other nation’s business. But in this case, suddenly, on this Saturday, 12 December 2015, it became every nation’s business to realize that the ultimate goal of development of all the other States around the table could not possibly be realized inside the limits of the given planet we call Earth and that their sovereignties were so clearly overlapping that they had to bow toward an outside reality – a strange form of new Sovereign. Hence Hollande’s enthusiastic salutation “Vive la planète!”.

Everyone could see that the proverbial lifeboats of the proverbial Titanic were too few for everybody – children, women, captains, orchestra, cats, dogs, lions, elephants, whales, butterflies and worms – to jump into and be saved. Finally, a real politicization of the impossible world order became visible to every diplomat.

Amusingly such a realization, even though it should have been taken as a state of war, had the unexpected result of not creating panic, chaos and havoc, but, on the contrary, pushing the participants into promising to sign a declaration that aimed at keeping the Earth’s temperature under an increase of 1.5° C, a goal that every expert considers to be ludicrously optimistic since temperatures having already climbed near or above 1°. A peaceful mood settled on the assembly that had realized that there was indeed a war of the world looming. Which does not matter much since, on Sunday, 13 December no one paid any attention to the “world historical” event anyway! The Bourget hall was swiftly dismantled and so was media attention. Is this not strange: a world event of no import whatsoever?

What I wish to do in this lecture is on the contrary to pay as much attention as possible to this paradoxical situation: the realization that the goal toward which nation-states have been modernizing themselves has vanished and that, nonetheless, there seems to be no way to change direction and to diverge even a little from the “business as usual” trajectory. At this juncture in world history the two positions are simultaneously true: the goal of the Globe has vanished and there is a total indifference to such a disappearance! We collectively behave as passengers in a plane to whom the pilots have announced that they are sorry to say that the landing strip on which they were supposed to land, “Ground Global”, is no longer on any map, and yet who sip their whiskey. Slightly disconcerted maybe, but on the whole, quiet and half asleep.

Some passengers, however, are not so passive. It cannot have escaped your attention that in almost all of the former sovereign states that had enthusiastically signed the Paris declaration, political movements are clearly setting their eyes on a completely different destination, one that does not have the Global Globe as their goal. The movement is global in scope since it is almost the same everywhere but it admonishes citizens to move away from anything Global back to another target that appears to be specific to every country – or rather that every country describes in strikingly similar terms: identity, protection, land, border, self, authenticity, natural, normal, local, united, homogeneous, sometimes ethnically pure. Let’s call such a goal Return to the Land of Old. Whether in Poland, Hungary, France, Italy, Holland, Finland, Denmark, and of course here in Germany, without forgetting the United States and Philippines, everywhere you hear the same calls for an abandonment of the pull toward the Globe and a temptation, more or less strident depending on the countries, to let one’s self be pulled back to a Land that seem to promise peace and protection. Even Great Britain, the nation that invented the Global reach, the Empire of the Globe, is now tempted to shrink back to the size of the tiny island it stopped being in the 18th century and to which it will be probably return forever after its “Brexit”.

To describe such a pull toward such a powerful attractor, political scientists are wary to use the notions of “populism” and “nationalism” and to brand those movements with the adjective “reactionary”. They are right to be worried. None of them is a remake of older political movements. They are all brand new inventions designed to absorb the airline pilots’ news: “Ground Global is gone forever; you won’t be able to land there”. Yes, the inventions are a reaction, but this does not mean those movements are simply reactionary: they have perfectly understood what was spoken from the cockpit: “You won’t modernize you fool, there is no planet big enough for all of you, you’d better find a safer, smaller and more protected landing strip that you don’t have to share with anybody”.

Is it not remarkable – and understandable – that just when the world historical event of COP 21 had concluded its inconclusive peace treaty (there is no common planet big enough for all of us; it does not matter anyway, let’s go on as usual), that people, tired of impossible promises, decide quite rationally to abandon the first goal and search for an alternative, no matter how limited, backward, even archaic it seems to the rest of us? But who are “we”, those who brand those movements as “reactionary”? Are we not the whiskey sippers in the plane dozing helplessly without any alternative maps? Should we not recognize that those reactionary movements at least are movements, they are moving somewhere – in the wrong direction maybe but moving all the same, while we are just stuck there in the seats, helplessly expecting some sort of miracle?

One of the many reasons we are stuck is that we are perfectly aware – history is full of lessons on that score – that the Lands of Old toward which those movements are trying to pull back all nations of Europe as well as the United States, don’t exist. Not only because, like the Global Globe, they are physically implausible, but because they are fantasy lands that bear almost no relation with the Land, the arch-soil (the Ur- Grund to use Husserl’s expression) that they are dreaming to reconquer again. What shape has the Poland that her new government tries to inhabit? How minuscule is the France that the so-called National Front tries to dig into? Who would deny that there was never any “Padania” in spite of it being where some northern Italians wish to reterritorialize themselves? I don’t think many of you would wish to inhabit the Germany concocted by the newly born Ultra-right. As for a Britain freed from Europe and the Globe, it is nothing but the phantom of an Empire long vanished – Great Britain becoming “Shrunk Britain”, as much a rump nation as Trump’s “Make America Great Again”.

It is at this juncture that the world historical situation becomes very tense: passengers in the plane have heard the pilot’s second announcement. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain again; I am sorry to tell you that the landing strip ‘Ground Land’ has also disappeared from view, this means that we cannot go forward or backward. We have to find an alternative landing strip that can be reached with the limited fuel we have left”. At this point, you understand that now all passengers are fully awake, frantically looking through the windows to detect a strip where the plane can land!

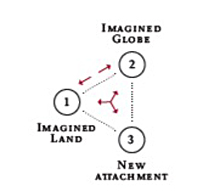

Since the Globe and the Land are no longer reachable, the first one because the planet is too small for our size and the second because those neo-nationalists offer a space much too small for us, we need to step aside (“faire un pas de côté“, as we would say in French). Is this possible? Engineers who are in the business of surveying will tell you that in order to define a position you need to practice what they call a triangulation, a simple application of the venerable principle of trigonometry by which, knowing one base and two angles, you may determine the third apex of any triangle without measuring it directly.

I want to employ such a triangulation to determine the exact position of a third attractor in addition to the two apexes Land and Globe, a third reference point the pull of which could make things move again, provided we accept its powerful sideways attraction. Let me give a code name to this third apex: let’s call it G, for Gè, Gaia or Earth, without immediately jumping to the conclusion that we know what it consists of. Take it as a concept, just as much as Globe and Land are concepts. What I am going to show is that the Earth is not the Globe. Both concepts, I am going to argue, are scientifically and politically wholly different and both differ just as much from the Land whatever way you consider it. At any rate my argument, as every sailor knows, is that we need to consider three positions not just two for any reckoning to work (and thus the only way to move toward prognostication).

To define the third attractor, we need to measure accurately the side we have already surveyed long enough – that is the line going back and forth between Land and Globe – and after that to detect in what ways the third attractor differs from both Land and Globe (the angles, if you wish to pursue the trigonometric metaphor that will allow us to triangulate its position). For a reason that is not simply aesthetic please note that I wish to pinpoint Earth below the other two, so that our triangle will be slightly slanted. (I will explain later why this is important.)

Let us first look at the familiar vector that relates Land and Globe. This vector is familiar to us under the name of “modernizing frontier” – I have studied its various features and enduring power for the last forty years, so you will forgive me if I sketch it much too quickly.

The political science version of such a vector is the one that allows people on the Left or the Right to situate themselves and thus to distribute the labels of “progressive” when you move forward to the Globe and “reactionary” when you move backward toward the Land of Old. Left and Right have to be made more precise, however, since, according to political scientists, the vector does not take the same meaning if positions refer to morality as compared to economics. You might be “progressive” along one dimension – economic globalization – and “reactionary” when considering mores – let’s say abortion or gay rights –; conversely you may be “progressive” on moral issues, while reacting strongly against globalization on economic grounds. And of course, you might also be “reactionary” or “progressive” on both accounts! Political scientists have a vast array of surveys, questionnaires and labels to fine-tune those positions.

What is clear, however, is that all such positions are situated along the single gradient going from Land – what you have left behind or wish to go back to – and Globe – the horizon you wish to reach or try to escape from – and that the cursor is defined by the modernization frontier that allows you to tell progression from regression. (Here I let you map out for yourself where you are and where you wish to position your friends and opponents.) And if you say “I am neither Left nor Right” it still means you are somewhere along that same vector, probably stuck in the middle. Since the modernizing frontier acts as a powerful ratchet allowing the disqualification of any position that is on the wrong side of the frontier (depending if it moves up or down), it is immensely difficult to escape from its weight; the Backward! and Forward! sign posts are to be followed without much discussion.

It is fair to say that what is called globalization is built, or used to be built, on the unexamined premise that the whole planet will end up modernizing toward some convergent omega point called the Globe. Until today, that is. I don’t think that any pilot could any longer announce with a straight voice that such is the real destination point of the flight. “Flight” is the right word: going Global was a flight of imagination. A dream so shattered that it has triggered the opposite dream, just as fanciful, of going back to a Land that – if by chance it could still be reached – would be totally destroyed. (What landscape would you discover if, for example, you attempted to go back to Fort Murray? To South Sudan? To your Heimat?)

To pursue our little exercise of philosophical trigonometry, we should now concentrate on the two angles. I will start with the Globe. How does traveling toward the Globe differ from attempting to land on the Earth?

Well, for one thing, in spite of the powerful image of the Blue Planet that we all have in mind, there is no stable point from where you can survey the Globe as a whole (a point well made by Peter Sloterdijk). To consider the planet as a Globe means that you imagine yourself in some sort of God-like position, let’s call it “the view from nowhere”, and that it is from this imaginary viewpoint that you take every older local attachment to the Land, to the Heimat, as limited, regressive, and archaic. For us, those who live on this land surveyed by this all-powerful Gaze, the Globe appears as an infinite horizon, an always-receding frontier.

In what way could the third attractor, the Earth or rather Gaia, be so different? Well, for one thing it is not a thick sphere but a thin pellicle, some say a skin, a few kilometres thick that no one can look at without being deeply drawn into it. You never watch from nowhere what the geo-scientists I have become friends with call ‘The Critical Zone’ and never do you embrace it in toto. It is layered, never flat but always seen in 3-D, always sideways. And the gaze of those who explore its many folds are always situated as much as are their instruments. For those of us who live in it – that is, for everything alive, terrestrial – there is no infinite progression toward a constantly receding horizon, but a continuous embedding in the ever multiplied folds of this multi- layered and ever surprising Earth (“Multi-layered”, by the way, is one of the traditional epithets of the mythological figure of Gaia).

How did earthbounds – the name I use to define former humans – end up directing their movements toward the Globe if such an horizon is not actually made for them and has meaning only when viewed from the outside where no one lives? This is the puzzle that anthropologists of modernity have always attempted to solve.

It is clear that three combined sources have rendered such a move irresistible. With each of the three sources, earthbounds felt they could be freed from all bonds and borders. They could become Modern Humans, that is, escape finitude altogether.

The first of those three sources is well known: it is the grandiose Galilean gesture of considering all planets as being essentially the same that has projected us, to use Alexandre Koyré’s famous title, from the Closed Cosmos to the Infinite Universe (note that a “closed cosmos” is clearly the way people embarked in the movement toward the Globe interpret the Land they attempt to leave behind). Viewed from the point of view of the Infinite Universe, the Land has a lot to do in order to shed its old attachments and to fully modernize itself. If the res extensa defines where we are all supposed to reside, then it has to be fiercely extended everywhere, which is of course impossible since life does not reside in space, no more than cosmonauts can survive in (outer) space without a space suit! Res extensa means something only when viewing the planet from nowhere.

Historians of science have shown, however, that such a pull from and toward the infinite universe would have attracted nobody if another immensely more practical pull had not been exerted, this time by the land grab (Landnahme) allowing Europeans to “abolish the land constraints” as Kenneth Pomeranz famously said. “Without coal and colonies”, Westerners would never have imagined that they could profit from the infinite cornucopia of progress and development. They would have remained prisoners on a fragile and limited Land, with the overworked soil of their tiny countries disappearing under their feet. Capitalism, to give it its name, is not characterized by its mundane, down to earth, practical and factual materiality but, on the contrary, by its extraordinary idealism – just as the res extensa is an idealist version of what matter consists of. And for the same reason: it positions the horizon outside as an ideal and pulls the Land from that nowhere into this nowhere. Nihilism in action through epistemology and economics.

The third source of such an extraordinary transmigration toward outer space is the political theology that has fused some of the ideals of religion with those of political emancipation producing the ever receding frontier of utopia – a place of nowhere for people of no place. Without this mystical appeal to the other world, neither the epistemological nor the economical flight toward infinity would have deprived the Earthbound of their common sense – that is, their sense of the commons. This is what Eric Voegelin has called “immanentization”, a process that has transformed politics into a perverted form of mystique without rendering politics more practical or religion more pious!

If you still wonder why passengers in the plane remain totally indifferent to the harsh news that the destination of the Globe has vanished, you now have part of the answer: they don’t believe the pilot! The whole point of imagining this infinite horizon is that nothing earthly counts anymore – the land, the soil, the Heimat are what has been left behind. The Globe is no longer concerned by what happens on Land. If reports of the ecological mutation do not push us into action, it is literally because we are not “of this planet”. The pull from the horizon of the Globe – the triple pull from science, economics, politics confused with religion – is dividing us so effectively that we cannot abandon the idea that we must fully modernize ourselves, shedding the old Earthbound in us in order to become fully human!

It should now be clear that the difference between directing one’s attention to the Globe or to the Earth makes for a pretty sharp angle. Science, economics, politics and religion are certainly not the same inside the limited but infinitely folded earthly Earth; each notion should be sorted out and reselected differently. This is what the curators of the ZKM show I mentioned earlier mean by a reset.

Still, we don’t know where this third attractor sits exactly. How could the Earth be so different from the Globe? Is this not too disorienting a direction? But be patient. Trigonometry requires us to define two angles not just one so as to calculate the third apex of the triangle. So let me now ask why directing one’s attention to the Land differs from trying to set one’s eye on the Earth.

I am pretty sure that some of you have been worried by my description of the “view from nowhere” as being the horizon dragging modernization behind. You might have been wary of its similitude with the endless complaints against the positivistic, disenchanted, objectivist, and soulless view of science, technology and capitalism that have been going on for as long as the words “modern”, “modernity”, and “modernization” have had currency. And you would be right, since such complaints are just another way to replay the bifurcated way in which the Land and the Globe have been pitted against one another – the lived world against the known world; the imagined soil of old against the real territory of the future; the deeply rooted folks versus the uprooted globalizers, and so on.

It is precisely to escape the repetition of this move that we need to shift our attention sideways. It turns out that if it is true that the Earth is much too small to hold the deadly ideals of the Globe, it is also true that the Land is much too small to hold the many-layered immensities of the multi-folded Earth we have yet to rediscover. As I said earlier, the Earth is just as different from the Land as it is from the Globe. That’s the beauty of triangulation! And it is this sideways move that could push us into action and give a new meaning to the Left/Right distinction, since another definition of progression and regression would be made visible as soon as a new target has been defined allowing us to measure what is moving forward or backward toward it.

It might be useful at this point to make sure that we take the attractor that I have called Land, “pays” in French, not as a primeval, autochthonous chunk of the world but as a concept. And what could be called a reactive concept, a concept that is always the counter effect of a movement toward the Globe. (Remember the energy anthropologists had to spend to protect the collectives they study against the exotic view of being “pre-modern” folks). Once modernizing has started, we have no idea of what the Land – toward which some want nostalgically to go back to – would look like. In France, when a Parisian mentions “la province”, no one should confuse this definition of the little towns left behind with what really happens in the said localities! Don’t ask Rastignac to describe fairly the city of Angoulme!

In other words, the Land is always a retrospective invention. And this is true of the real old one – Husserl’s arch-soil Ur-Grund – just as much as of the various forms of neo-nationalism that we see sprouting everywhere as a reaction against the sudden and unexpected disappearance of the Globe. Remember what the pilots announced to their passengers: both destinations have vanished from their radar.

The striking difference between the Land and the Earth, that is, the sharp angle we are obliged to measure, is that the Earth might not exactly be part of nature. Nature, as a modernist concept, had the strange quality of being the universal ether in which everything was supposed to reside, from my body to this lectern, this building, Berlin, all the way to the Big Bang in one single continuous stretch and submitted to the same laws. Such a concept of nature is much too vast, so vast that there is no way to live in it and feel any sort of protection. This is why naturalism can never be a lived form of life but only an ideal, and we now realize how dangerous an ideal it is. At least since Pascal, we are well aware of this feeling of uneasiness and even angst at the view of such an oversized, cold and infinite space. And no wonder. This conception of nature is directly linked to the horizon of the Globe, not at all with the very different entity called Earth, Gè or Gaia.

Compared to the concept of nature, the concept of Gaia is local. It’s a ring of active life forms that have molded their many overlapping niches in such a way that they provide one another a series of envelopes that can in no way be stretched and smoothed in the form of the res extensa. As I have shown elsewhere, in a gesture exactly opposite to that of Galileo, James Lovelock has brought the laws of physics and chemistry not only down to Earth, but down to this interlocking swarm of active entities, this thin pellicle of life forms, the resulting effect of all of them being to maintain a somewhat protective medium for future life forms. No more, no less. Nothing as grandiose as the infinite universe, but nothing as restricted as the tiny Land that has been left behind.

Such is exactly Lovelock’s thesis: contrary to Galileo’s conceit there is something special about the planet Earth, something that has been totally overlooked when it is considered from the outside as one Galilean body among an infinite number of Galilean bodies. This does not mean that the Earth is alive as one organism; it simply means that it is not dead. For one thing it is finite, and indefinitely folded. For another it is incredibly reactive to our actions. Nature was indifferent to our actions but for that reason it could be mastered. However, Earth as Gaia is terribly reactive (even ticklish as Stengers would say) and for that reason escapes all our hopes of dominating it.

That’s what it means to be facing Gaia: let’s face it, we have no longer any idea of what it is composed. And now that we have learned how reactive it is by having modified it so much that we know even less than before. As any insurance company will tell you, the capacity to prognosticate what is coming has never been as poor as it is today, for the reason that the earth sciences are in effect historical disciplines relying on a record of past experience that is now of no import whatsoever. With immense surprise and total bewilderment scientists of many disciplines suddenly realize how limited, complex, local, impossible to scale, and unpredictable the soil, climate, and ocean could be. We see the sudden resurgence of the natural history necessary to follow the geostory of a very local and highly reactive Gaia. The disinhibition of the past century has made most modernizing humans actively forget what the Humboldt brothers would have likely had no difficulty relating to.

If you remember the cliché of history of science according to which Galilean physics had to leave aside all forms of generation – the old definition of phusis – to consider only movement of volume in space (the definition of res extensa), it would make sense, if we wanted to redefine cosmology, to carve out of the vast expanse of Nature a little ring, Gaia, Critical Zone, whatever you name it, and consider that we are not much concerned by Nature but rather terribly interested by Phusis – inside which we are folding ourselves. So let’s cut out Phusis and leave everything else to Nature (a counter intuitive but on the whole meaningful return to the old idea of an infra and supra lunar divide).

If it makes sense to draw the limit between Phusis (the Gaian pellicle) and Nature in general, it is for another reason crucial for the war and peace situation into which we have entered. Nature is a domain of relative epistemological peace for the good reason that there is not much room for the famous Whiteheadian notion of bifurcation between primary and secondary qualities, or between the known and the lived world, or the objective and subjective version of things. Whatever you think of the Big Bang, or of the magnetic core of the Earth, there is no plausible sense in you discussing what scientists say of those entities since you have no credible additional access to them. They are best left to scientists who have a complete monopoly over their definition, that is, over the instruments and calculations necessary for making sense of those distant entities. If you contest the definition of those “natural” phenomena, scientists will have no difficulty in saying that this is your own personal, imaginary, poetic, subjective view. Bifurcation is easy to make but of no import whatever.

Things are entirely different inside the newly drawn cosmological domain of Phusis – the limited, restricted, local, active and reactive Gaia freed from the concept of Nature. Here, for each phenomenon, a vast array of practitioners have alternative views of what those entities are and how they should behave. The philosophical notion of bifurcation between primary and secondary qualities cannot and should not be peacefully settled. Gaia is not a place for epistemological peace but epistemological warfare. Ask a farmer what he or she thinks of agronomy; an Amazonian Indian what he or she thinks of modern agro forestry; the executive of an oil company what he or she thinks of climate science; the laid off worker of a bank what he or she thinks of the “law of economics”! No discipline any longer has the power to disqualify those claims and transform them into subjective or archaic versions of what really is.

One of the great differences between Gaia and both Land and Globe is that the conflicts between Science and Tradition (oracle and prognosis?) can no longer played out. The bifurcation is resisted everywhere and with good reason since no one on Gaia has the dream of teleporting oneself toward a view from nowhere, or shrinking back to the Land of old. Phusis is a world to be rediscovered by all agents that make it up. The disputes have to be settled from an entirely different point than from the view from nowhere. Scientists have no monopoly; moreover, they no longer have the implausible role of ushering live forms into the world of beyond. In other words, they have much better things to do than extending the utopian domain of res extensa. They have to rediscover the Earth; they have to prepare the landing strip so that the passengers in the plane – remember those who had learned that the two former destinations had vanished – might find a place to land.

Much more should be done to give sense to this third attractor, the one I have called Earth or Gaia. Still I think my little exercise in philosophical trigonometry is not too much off the mark. The baseline going from Land to Globe is well known and the two angles are sharp enough so that a rough localisation of the third apex can be envisaged. At any rate what counts is that citizens, activists, scientists, and politicians everywhere have clearly diagnosed the total implausibility of the two main destinations toward which the present political dilemma is leading them.

They all feel that, as the pun recently written on Paris wall put it, “another end of the world is possible” and they are ready to reinvent everything from the way we eat to how we sort ourselves, build our cities, reshape our bodies, raise our children, save our landscapes, till our soil, and more. But the problem, what limits their moves so much is that, every time they offer a solution, explore an innovation, or assemble a new group, they are asked to place themselves along the Land/Globe vector and answer the question: are you Left or Right, progressive or regressive, local or global, archaic or innovative? Even they all know full well that the question is not enough to orient themselves because neither of those two attractors is what pushes or pulls them. And they are not allowed to say that they are neither Left nor Right. This is why I think it might not be totally senseless to tell them: “Of course you are not at ease with the traditional reference system; it is oriented by two locations that have no existence – one because it promises infinity, the other because it promises immediacy. As we show in Reset Modernity! exhibition ‘Let’s touch base!’ It is time to land somewhere. To come down to earth. To rediscover the indefinite multifolded Earth.”

Paper given as the Mosse Lecture, Zukunftswissen, Humboldt University, Berlin on 12 May 2016.