Many women stepped out to mark 25 November, the date designated by the United Nations as International Day of Action against Violence against Women, and now the start of Sixteen Days of Activism worldwide on this theme. A couple of weeks before, on 11 November, a very different population had been on the streets. It was marking Remembrance Day and, mainly men in military uniforms, they marched in memory of the 30 million fighters in all countries, also mainly men, who fell in the First and Second World Wars.

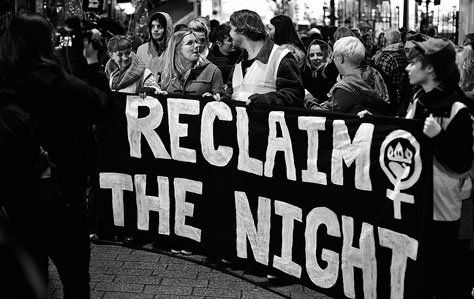

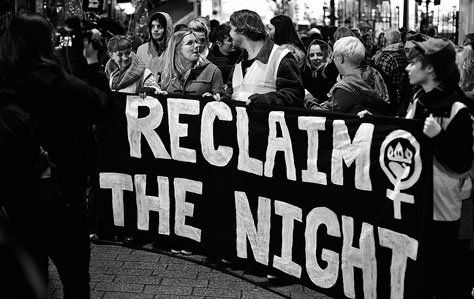

Reclaim the Night, 2012. This year, London Reclaim the Night celebrated its tenth anniversary. Photo: Morten Watkins. Source: Flickr

As I was reading the morning papers and scanning the Web on the morning of Remembrance Day, musing uncomfortably on remembrance and war, I came across enthusiastic mentions of a newly-issued video game: Advanced Warfare. It’s the latest in the series Call of Duty, the product of Sledgehammer Games, a subsidiary of Activision. An earlier game in the Call of Duty series, Black Ops 2, had broken all records by grossing half a billion dollars in sales in the first 24 hours, twice that much in the first 15 days. Advanced Warfare, they predicted, was set to outsell it.

Sledgehammer’s recent products are what are called “first-person shooters”. The gamer chooses, holds and fires a weapon. “You” aim and fire it. You score by “wounding” and “killing” your opponents. On the website PCGamer, the reviewer admired the addition of new weapons in this update of the game. “Guns are littered everywhere and they’re fun to shoot: big, powerful, varied, some punching single shots through armour, others spraying corridors with death […] the animations and sounds and dramatic death animations are addictive feedback. There’s even a beam weapon […] and heaving its energy stream between targets, watching them drop and die, is disgustingly satisfying.” With the new exosuit that gives the wearer superhuman powers, he went on, “I’m a walking, running, jet-jumping massacre”.

If there’s no one among your close acquaintances who can give you an introductory massacre on their state-of-the-art XBox console, look instead at a YouTube clip of Advanced Warfare that enables you to try out your talent for slaughter. Prepare to be deafened and blinded by impacting bullets, exploding flesh, equipment and buildings. But also, as David Crookes insists in his review of Advanced Warfare, be ready to “feel at ease”. Your controller “vibrating violently”, you cannot fail to admire the script writers’ “crisp dialogue”, he’s insists.

My reason for dwelling on the game in the context of the Sixteen Days of Action against Violence against Women is not to suggest that Advanced Warfare is a woman-killing pastime. In a rival game, Grand Theft Auto, it had indeed been possible, for instance, to choose to have sex with a prostitute and then shoot her instead of paying. No. Sledgehammer Games warns against “toxic” and “misogynistic” play. Indeed in Advanced Warfare you have the option of adopting the persona of a female shooter (interesting to speculate who, and how many, make this choice).

The game is, for all that, profoundly gendered and everything about it, including its marketing, is unmistakeably designed to appeal to men and boys. And the phenomena of endemic male violence against women, on the one hand, and the militarization of the dominant form of masculinity in our culture, on the other, while they are not the same thing, are not unrelated. Gender runs through the continuum of violence in contemporary society, linking, explaining and sustaining its different manifestations. It is no accident that, in the UK, 90 per cent of those serving in the armed forces, trained for socially-endorsed violence, are men; while 95 per cent of those committing violent crime are men, and 99 per cent of those committing violent sexual crime are men. (As a footnote here, I must add that the scarcity of tables specifying sex of offender in the UK government’s statistical reports on crime is difficult to credit, let alone explain.)

Specifically, the gender relation as we live it involves an association of men and masculinity with physical strength and a readiness to use force, with rivalry and confrontation, with attack and defence, with weaponry and warfare. It’s a relation in which masculinity and femininity are markedly differentiated, contrasted and ranked, inviting misogyny and naturalizing men’s control of women, ultimately expressed in rape, battering and other forms of gendered and sexual abuse. The uniformed, exosuited and rocket-toting man that Advanced Warfare enacts, promotes and sells is brother to the controlling, sexually-privileged man who is favoured in our contemporary everyday cultures.

However: though force-full masculinity is prevalent and celebrated, there is a counter-current of opinion today that seeks something different, that aspires to a culture of equality, co-operation and peace. We have seen it in November in the UK, with the wearing of poppies, some of them pacifist white. We have heard it in the chants of women parading through central London to “Reclaim the Night”. We recognize it in the small but persistent White Ribbon Campaign of men working to end violence against women. The UN gives expression to this counter-current when it warns us that, worldwide, if we do not act to prevent it, at least one in three women will be beaten, coerced into sex or otherwise abused by an intimate partner in the course of her lifetime. So do the world’s peace movements, when they call for an end to the ongoing armed conflicts that in 2013 caused a civilian and military death toll of 128,000.

But act how? Respond how? Implicit in our concern about violence in peace and war, and the part played in it by masculinity, is dissatisfaction with mandatory gender types that deform and limit us as individuals. We have even developed during the last half-century a social theory, convincing to more and more people, that the complementary duality of masculinity and femininity, their marked differentiation, is not destined by biology but amenable to social shaping. The trouble is – we seldom bring this possibility to view, and even more rarely do we give it expression as social policy. We may have grasped the concept of socially constituted gender, we may have out-theorized those who shrug and say “it’s all in the genes”. But where, concretely, are the social programmes that openly address transformative change in gender relations?

Where are the purposeful measures in education, youth work, sport, vocational training that might have shaped Kabir Ahmed, 32, British father of three from Derby, in a masculinity different from the one that led him to fight and die for ISIL? On the very day, 11 November, that I first read of the launch of the new video game, The Guardian carried an article about the death of this young jihadi in a suicide attack in Iraq. In an ISIL podcast some months before, Kabir had described his life with Islamic State as “freedom, totally freedom […] the good life, actually quite fun”. He said, “I walk round with a Kalashnikov if I want to; with an RPG [rocket propelled grenade] if I want to.” He added, “It’s better than, what’s that game called, Call of Duty? It’s like that but, you know, 3D. You can see everything’s happening in front of you. It’s real, you know what I mean?”

This article was originally published in 50:50’s series on 16 days: Activism against gender-based violence 2014