Barbara Gaile belongs to the generation of artists that grew up in Soviet Latvia. She got her academic education in times of total chaos and was probably the first to graduate the Art Academy of Latvia with abstract compositions. In the mid 1990s, Gaile went to Paris where she continues her creative explorations in abstract painting. Before her departure, she left her mark on the Latvian art scene: “Barbara Gaile’s ‘expression’ was also successfully attained in spatial works, mastering the closed interior of an exhibition space (Absolutely Red at Gallery M6 in Riga, 1995), a ploughed field (within the project State, 1994) or ruined buildings in Pedvale (the exhibition Geo-Geo, 1996). Still, her concentration on the planar surface of the painting as a restrictive factor remained the most important. Her trip to Paris in 1996 and a lengthy stay there only promoted this tendency. In Paris there was a chance to see her conception and practice against the background of the infinitely varied artistic life of the large city (‘you always live […] close to something totally opposite’).”

She has successfully avoided being personally dragged into domestic debates about abstract painting. “The greatest danger zone for the decorative tendencies in Latvian painting turned out to be abstractionism, whose concept was populistically pronounced to be incompatible with the nationality (in statements of Latvian artists of the older and intermediate generation); in turn, their efforts at abstraction have most often been of an experimental nature, and even unequivocally abstract paintings do not lose their connection with imagery and figurativeness.” It is hard to believe that in such an intolerant cultural environment it could have been be easy to continue with what had been begun and to achieve the level we see today in Barbara Gaile’s compositions. To me, Gaile’s paintings seem like spaces of experienced emotions and finished thoughts, because each layer of pigment laid down is like a person’s lifetime in which every new experience forms the next layer. But in order to stop myself from falling into poetic musings on the physical features of dry pigment, refracting light, the materiality of pigment, and possibly to avoid being mistaken: one hot August day I had the wonderful opportunity to speak with the artist and to seek the right words. Now on visiting the exhibition Perles (Pearls) at the Latvian National Art Museum, every one of us may be able to obtain a broader, and perhaps in Gaile’s case, a deeper understanding of her paintings. Because everything started with the artist wanting to obtain such intensification of colour on the plane of the painting “that you want to thrust your hand into it”.

Liga Marcinkevicha: A painter is in such a complicated situation: you work with each composition separately, but then in the exhibition each painting becomes the competitor of another, or all of them are suddenly valued according to one common denominator. How do you work, when preparing for an exhibition? Have you one combined story in mind, consisting of all the exhibited paintings, or should each painting be seen as a separate, individual story?

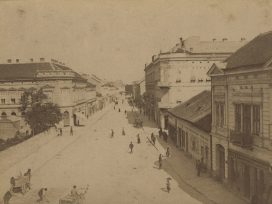

Barbara Gaile: Both. This exhibition will also feature works created earlier, but in general there will be 33 new pieces, and while creating them I saw them as a dedication to the Latvian National Museum of Art, based on my childhood emotions and memories relating to it. When I attended Rozentals School, the place was special and it felt as if you were now admitted to the starter group. And then whilst at the academy we went to the museum to paint copies. There was a fellow-student of mine, Janis Vinkelis, who would suddenly during the break propose going to the museum to view an exhibition. Why not! He also had the idea – why look at an exhibition slowly? You have to look quickly, as if filming. I remember sweeping through the White Hall like the wind. The museum is a place with a particular, powerful aura. And that entire environment – remember, there used to be some gathered curtains – led me to the idea that something special should be exhibited there: real pearls.

I’ve been interested in pearls for years, reading, inquiring, exploring and working with mother of pearl. Of course, there are also the symbolic meanings of pearls. In nature, the pearl is a wonderful reaction to an external aggressor. A grain of sand gets inside the oyster shell and, terrified by this, the oyster generously coats it with nacre. In my opinion, the pearl is a true natural wonder. There are absolutely perfect pearls, like ideal spheres. And there are baroque pearls, a kind of natural error. That is what they are called – baroque pearls. They are deformed and their shapes are one-offs, they look like a failure, an aberration, but are still beautiful and unique.

The exhibition will be about the beautiful, about how much it is both an illusion and a reality. The form of several works is perfect, but in the working process I realized how much I am fascinated by the opposite – the robust, the ugly, the rough, as it is also in nature. In reality it is realism to some extent. Not realism in terms of painting but realism at the level of senses and perception. The works will be diverse. Eliminating all that is not essential, the human is alone in this world. In the most critical moments of life I feel this very acutely. Of course, there are parents, family, house and street, the state, and you kind of get taken over by this context. In painting I’m interested in talking about the essence, the existence of emptiness, about things that are missing.

LM: How did you come to concentrate on the plane in painting? In the mid-1990s, you created works in space and the environment (at the gallery M6 and at Pedvale).

BG: The thinking, however, in my case is spatial. At Pedvale and with M6 there was the opportunity to do it in space, later there weren’t so many of these sorts of opportunities (Bristol and Deauville). I liked it a lot and it was interesting to create a work of art in space or in an environment. And yet, if regarded with hindsight, it was a field that I put in a space or a landscape. But now I focus this onto a plane. I like the moving image, and photography too, but I understand that to work professionally in other media, I need training, I need time. I have already been trained in painting, even though it may seem that I’m not actually using it.

LM: How would you explain your choice of colours? In 1995 it was red, but now it is something quite different – a mother of pearl pigment. How did this transition from pure colour to intermediate tones happen?

BG: Very gradually. I was already using dry pigment at Pedvale. I remember that there was cadmium pigment brought to M6 which they didn’t want to show me because there had been some mistake, but I asked them to unpack it just to have a look. And when I saw those small jars I thought that my eyes would remain in that dry pigment. At the time I worked with very intense colours: it seemed to me that I had to paint very, very intensely. Through the method I worked with, spreading and lacquering, the colour was heightened. I thought that I had to paint a picture that you would want to thrust your hand into.

After that there was a period when I started to work with pigments that were more matte, which seemed to absorb light. At one stage there were dark paintings – dark, dull, absorbent paintings, like coffee grounds. Gray. Flint. Black. And then one day in a Paris paint shop I found mother of pearl pigment. It looks like a light powder, without distinct colour. When I took it into my fingers, I thought – yes! This is it! For some time I just had it at home, and then the moment came when I felt that I could try to understand the material. You see, it’s quite interesting with these pigments – on the one hand they are tasteful, and then you get a nuance just slightly different and it becomes insipid, banal, tacky – which is also interesting. Then a little more and the intensification becomes unbearably sharp and shrill. While you’re working you have the opportunity to heighten everything to something horrible, threatening, tragic. And I think that with this material you can obtain a very wide and expressive range of feelings. Of course the preparation of the canvas plays a role. The pigment can be laid in various ways. It looks different in different lights. The pigment layer is very thin, as if there was nothing, although there is so much.

LM: The pigment is like a powder?

BG: Yes, but if you look at it under a microscope, its surface is as if covered in scales. It’s the same with pearls. And these scales, super-imposing on each other, create the different reflections. Of course, the quality of the material also matters. I think that the material I use comes from the world’s top pigment mills and is being developed all the time. Sometimes, when I talk about the process of creating a work, my husband admonishes me for revealing my professional secrets. But I know that it is impossible to imitate and copy. It’s my layering, the way I work that I’ve discovered for myself. It’s my kitchen.

LM: Is it your own way of meditation?

BG: There’s nothing meditative about it.

LM: That’s how we like to think of a work of art and the way it was created.

BG: I think that the people who like my paintings could perceive it that way. The process of creation has a certain aggression, with large formats it is also physically challenging. That’s why my canvases are not very big, as my reach is limited. I remember that feeling when I opened the pigment jar, and looked into it… as if it were today. Well, you know how it is. You look and realise that – yes! This is it! You simply catch sight of a universe of possibilities.

LM: For an artist it is nearly impossible to explain why. There must be art critics who can remove your pigment coating, layer by layer, down to the canvas and explain.

BG: Yes. And an art critic also has to be someone who sees the structural make-up of an artist’s personality to an extent, in order to understand why exactly that path is interesting and why one chooses to work that way.

LM: In my opinion, your working method involves a high level of stress because in your case it’s clear when the work has begun, but you don’t know when the work will be ready.

BG: Yes, there are works like that… In the exhibition there will also be a black picture, and it will have to be lacquered before the exhibition so as not to get inadvertently damaged. I believe it took me almost a year to lay the base for it. The idea was that it would be like the side of a black grand piano. And during that year, from time to time I had the feeling – well, surely, it must be finished. However, I understood that no, it wasn’t, not yet. In the creation of this painting the time factor was particularly important. The work has no obvious raised surface and no mother of pearl. It is black, sleek, mighty – like a requiem.

At that moment when I am laying the pigment, I try to make sure that no one else is at home, because for a couple of hours I need peace and silence. The movement you use to apply the pigment is an essential element. When the pigment has been applied, you have to react, to assess. If you’ve been successful, you can leave it, if not, you have to decide what can be done. Or you have to wash it off. In painting, even an accident can be redirected, developed, transformed and brought to perfection. In the working process you have to be open so that you can evaluate and react, and decide. Sometimes it happens that I’ve been covering a canvas for months and then, while putting on the pigment, I realize that everything is totally wrong, and then I am overcome by despair. To recreate a new opportunity again, you have to spend lots of time applying acrylic and preparing the base.

At other times, it seems – well, I’ll try again, a bit differently, wash it off or whatever. And precisely that’s when it happens. From abandoned hopes and lost illusions (getting rid of the requirements set for yourself)… that moment when you almost retreat, accept failure – sometimes in such moments something interesting is born.

LM: Something else arises, something that you haven’t been able to foresee. You can only trust in it.

BG: Yes. It’s moments like these where you must follow the chance happening, it’s as if it provokes you to follow it.

LM: Isn’t your working method similar to your creative life – looking into the pigment jar in the paint shop eliminates the academic training?

BG: I’ve done everything quite deliberately – I really wanted to go to the Rozentals School, then the Art Academy. The academic requirements at the academy were all very interesting, up to a point. Indulis Zarins allowed us to paint quite freely in the senior courses. I finished the academy with completely abstract works. I remember as if it was yesterday how Imants Vecozols barged out in the middle of my examination. He felt insulted that something like this could happen. In the final years at the academy you learn figural composition – that was interesting, but I realized that it didn’t attract me. I wasn’t drawn to Latvian figural painting. I thought, well, why people and not animals, for instance. When I started at the academy, an undoubtedly significant and important event that rocked me was when I was in the US and I saw Mark Rothko’s large canvases, Miro, Barnett Newman, other American classics. And I thought – yes, that’s something that seems great to me. I also became aware that a freshman can’t work immediately, just like that, but needs schooling, in my case the academy.

And when I was already working on my diploma work, I did it very independently, in my workshop. When the director Indulis Zarins asked me to bring in sketches, they were just rough drawings with pen and pencil. I told him what and how I envisaged it all, and Zarins reacted positively – yes, keep on working. Today I understand that this demonstrated amazing trust. I’d painted quite a lot, as I had my first solo exhibition in the gallery G&G that year, and when I had to choose the final compositions for graduating from the academy, I asked Zarins to come to my workshop. This visit was a whole process, he wanted me to fetch him from the academy and then we went to the intersection of Lachplesa and Barona streets where I had my workshop at the time. I showed him all that I had created, waiting for his comments – what work to choose, if it’s even suitable. These were absolutely abstract, minimalistic compositions. Even if the answer were to be negative, I would not be able to paint anything else, because I couldn’t force myself to work otherwise. Zarins told me to make my own choice on what to present to the academy panel of examiners. For me this was a shock, as I wasn’t expecting that I’d have to make my own choice. With the experience I have now I think that the way Zarins acted was delightful, that he didn’t put himself in the position of an all-knowing authority and did not specifically point out any of the works. He saw that I was in a kind of a process and should be left to deal with it myself.

LM: At the moment, the tendency in art is like this: there is the artwork and then the story of the artwork. You, however, mostly stop at the point where the artwork has a name but give no further indications to the viewer. In my opinion your paintings lead to a story, but perhaps some viewer might feel uneasy and have doubts about whether they are going in the right direction.

BG: I could easily provide the three X’s, but I do give names to the works. With this I indicate the direction of thought. Sometimes I already know the title of the work when I start it, and sometimes I don’t. In such cases it’s just my feeling of what it is all about.

LM: In this new century artists themselves are trying to tell us more about their work in order to purify it from false or incorrect references that the viewer could attribute to it. But you leave the interpretation to the viewer.

BG: That’s how it should be because the artwork, in my view, has to be a kind of screen of confrontation where the viewer is confronted. The artwork gives an impulse, and what follows is left to the viewer. This is what is interesting. Also for works of a literary trend where the medium is the narrative there are innumerable possibilities of interpretation. For example, if you interviewed a hundred different erudite persons to tell us about a work of art they’d seen, there would be a hundred different variations. And that’s what should ideally be the case in art. An artwork must be like a poem, a haiku – so short and so loaded with meaning, and at the same time as if incomplete with something missing. It’s the same with the title.

LM: It’s certainly an axis for evaluation.

BG: There is also a choice – to read or not to read the title. You can view an exhibition without reading the titles or the annotations. But you can also take an audio guide, which tells you EVERYTHING.

LM: And yet… Each of your pictures has its own personal story and history.

BG: Of course. But the moment I finish it I am able to distance myself and I no longer think about it. Each work is a unique world in itself. And yes, other pictures even have several stories, my well-considered layers of memories, materiality and association, my intellectual accumulations.

LM: The arrangement and the placement of works in the exhibition also play an important role in how the exhibition is received.

BG: At first I wanted to fully delegate the installation of the exhibition to someone else, as if to distance myself from it. But then, while unpacking the paintings, I realised that it is important for me what painting is located adjacent to what other painting. Now I am working on a catalogue and arranging pictures, and I understand that the order of the images is important to me. It’s not about what pictures suit each other, but rather pictures develop an internal conversation and are mutually enhancing. At the same time each picture works independently, in its own right. A number of pictures are even separated by a distance of several years.

LM: Of course the space and the architecture determine very precisely the boundaries and direction of your exhibition. Every artist has an ideal way of being presented vs. the real one.

BG: Yes. Right now, in August, the lighting in the White Hall of the museum is very good. Currently, the exhibition is different to how it will look in October, when autumn arrives in Latvia.

LM: Where do you find the motivation for painting? Or is that an issue you don’t think about and it’s just a way of life?

BG: From time to time I’ve asked myself this question. There have been moments when it has felt as if I’ll finish this and that will be it, no more. But I think that if I have stuck with painting for so long then it is vital to me, it comes from my childhood. At home my Mama had a painted sketch for some stage design by Liberts on the wall. It was an image that drew my eye to it every day. I liked to sink into it. Recently, I saw this sketch again and it surprised me, because in my memory it was so much more impressive. It seems to me that if you want to “ruin” children with painting, you only need a few pictures or art albums at home or at the neighbours’. My childhood home was next door to Liberts’ house. Of course it’s not just this artist, but also all the art books and the exhibitions that open another world that you dive into, the Hermitage… Anyway, I don’t know what gives rise to that strong fixation – the impressions of childhood, school, the skills of the craft that are so important to a painter. And there is something so essential about why it is exactly painting, and why exactly the desire to create a universe within a rectangle. I like, am fascinated, and also driven by the opportunity to create a fabulous dimension – a room of pure thoughts and associations. This, in my opinion, is the direction in which painting can still develop. It is a very finely-wrought, delicate path. It demands great openness, virtuosity and a fragile sensitivity from the artist. It is like safe cracking: you have to operate carefully.

LM: Your works are not reflections on the “superabundance of visuality”, but rather a field, a place to free up the flow of associations where there are no superfluous, instantly associative, perceivable visual images.

BG: I think it is less important, to for example solve social problems in art. Yes, I can evaluate this professionally, but that’s a different conversation. I’m not participating in it. I’m interested in freeing the plane of painting from the convolutions created by life.

LM: Is it possible to weigh or assess what is important in art?

BG: I don’t think it can be evaluated. It is a completely individual matter for each of us – what is important is to speak honestly, of course, not to go whichever way the wind is blowing. Art has to have an intellectual base and direction. It is essential that your actions as an artist do not descend to an amateur level where you alone get a kick from the activity – if that happens it’s sad. But when you talk about art, you’re discovering, pursuing a theme – that’s where it makes sense. Endless creativity is a form of existence which is not an end in itself. If it becomes like that, then it’s amateurism.

LM: Do you agree that for an artist an exhibition in a museum is a very important milestone, experience, a point of reference?

BG: Yes, of course it’s important. But I don’t know why I agreed to something like that. As regards the Latvian National Museum of Art, it was the aspect of emotional attachment that was of significance. At the same time, it also means to ask yourself how far you are with all that you’ve been doing all these “zillions” of years. In my case, an exhibition in a museum is by no means a solution. It is more like a sentence with a question mark. The exhibition has emotional significance, because for me the museum is a repository of wonders and revelations. The museum presents possibilities for deep discussions with the artworks and with yourself. It will be a new experience for me.

LM: Who do you look up to?

BG: I used to think that I would be able to name a specific artist, but not now. There are particular works of art that still enthuse me. The question of inspiring figures is interesting when you read annotations, for example, on works of philosophers, and then you read the works yourself. And in the reading process you start doubting, and those doubts are already the main thing because it’s a thinking process. It is similar with artworks, for example with exhibitions that have been created by some brilliant curator. While assessing them you realise that all is not quite so cut and dried. There have been periods when the opinions of authoritative figures have been important, and undeniably it helps and is important for development, but with time you come to see that it is not the determining factor. At the same time it’s not so straightforward because at that moment you understand that there’s nothing else.

LM: Well, yes. This is what you put at the centre as the axis. You either put authority or you put yourself and your doubts in the centre. And then you become the little stone that causes the water to ripple.